Fembio Specials Black History Toni Morrison

Fembio Special: Black History

Toni Morrison

(Chloe Anthony Wofford [Geburtsname])

born Feb 18, 1931 in Lorain, Ohio

died Aug 5, 2019 in New York, New York

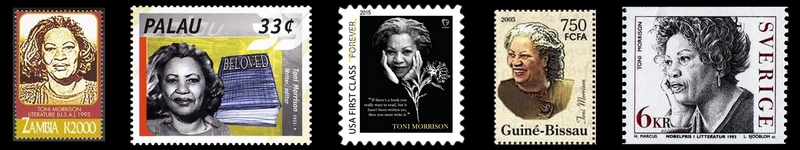

African American author, editor, lecturer, professor, Nobelprize for Literature 1993

Biography • Quotes • Literature & Sources

Biography

Recognized after the publication of her 6th novel Jazz by the Swedish Academy as “a literary artist of the first rank” for writing novels “characterized by visionary force and poetic import, (giving) life to an essential aspect of American reality, ” Toni Morrison in 1993 became the first African-American and the 8th woman to win the Nobel Prize for Literature. From the publication of her first novel, The Bluest Eye, in 1970, Morrison has struck the literary world with her rich language and powerful, complicated portrayals of the individual and communal struggles of African-Americans, within the racist and sexist context of white American society. Noted for her detailed, realistic development of personality and character, Morrison’s writing achieves a complex exploration and varied characterization of black women especially. Morrison’s novels often develop themes of the difficult quest for personal freedom, the journey to self-discovery which shares in and recovers family history and communal heritage. Her writing has been heralded for the vibrant and lyrical quality of her prose, capturing the sounds and speech of Black America, as well as the mythic, folkloric, and supernatural elements shared through African American oral history.

Morrison’s own family history and childhood experiences clearly have been a well-spring of inspiration for her themes and language. Born Chloe Anthony Wofford, Morrison grew up in Lorain, a steel-mill town in Ohio. While her father George Wofford, a shipyard welder who held down three jobs simultaneously, believed adamantly that white racism was unchanging and distrusted the humanity of whites completely, her mother Ramah Willis Wofford had faith that race relations could improve in the US. Her grandparents too, argued over the future of the black race in America. Thus, Morrison says she was raised in “a basically racist household,” where the core belief in the values and virtues of black culture and community was commonly held philosophical ground. Folklore and storytelling were an integral part of her family life.

Morrison’s own family history and childhood experiences clearly have been a well-spring of inspiration for her themes and language. Born Chloe Anthony Wofford, Morrison grew up in Lorain, a steel-mill town in Ohio. While her father George Wofford, a shipyard welder who held down three jobs simultaneously, believed adamantly that white racism was unchanging and distrusted the humanity of whites completely, her mother Ramah Willis Wofford had faith that race relations could improve in the US. Her grandparents too, argued over the future of the black race in America. Thus, Morrison says she was raised in “a basically racist household,” where the core belief in the values and virtues of black culture and community was commonly held philosophical ground. Folklore and storytelling were an integral part of her family life.

They all told stories - my mother, father, grandmother. The children were called to tell stories - to remember them, to perform them, to change them, even….The storytelling were survival stories, to make us, and the race, confront the terrible things that were happening, to know that something evil was out there, but you could protect yourself through cunning and wit, by strength.

(Morrison: Denver Post Nov 16 2003)

Morrison entered her multiracial kindergarten as the only child able to read. Through her childhood she read voraciously, especially enjoying European and Russian authors, like Austen, for the vivid and accurate depiction of their cultural milieus. Having received occasional criticism for writing exclusively about black society and characters, Morrison recalls this early literary influence:

When I write, I don't translate for white readers…Dostoevski wrote for a Russian audience, but we're able to read him. If I'm specific, and I don't over explain, then anyone can overhear me.

(Morrison: Newsweek)

After graduating from high school with honors in 1949, Morrison attended Howard University, a prestigious, traditionally black university in Washington D.C., where she received her B.A. in English in 1953. There Morrison was disappointed by the superficial social scene, and by categorization and segregation within the black community by skin tone. She spent a great deal of time traveling with a theater organization of students and faculty. In 1955 Morrison earned a Masters Degree in English from Cornell University with her thesis about suicide in the works of Virginia Woolf and William Faulkner.

She went on to teach English first at Texas Southern University, returning to Howard University in 1957, where she met and married Jamaican architect Harold Morrison the next year. Though Morrison had two sons, Harold Ford and Slade Kevin, from this marriage, it ended in divorce in 1964. During this unhappy period at Howard University Morrison began to develop her writing when she joined an informal group of writers who met monthly to read and critique each others’ work. After exhausting her supply of writing from high school, she finally produced a short story about a little black girl who wanted blue eyes, a story that led to her first novel. Morrison said of this difficult time in her life “it was as though I had nothing left but my imagination…I had no will, no judgment, no perspective, no power, no authority, no self – just this brutal sense of irony, melancholy, and a trembling respect for words. I wrote like someone with a dirty habit. Secretly. Compulsively. Slyly.” (Morrison: Current Biography) After leaving Howard University, Morrison became an editor for Random House, eventually moving to New York City.

During this time, hard at work as a single mother, Morrison began to develop her short story into the novel The Bluest Eye, which tells the painful story of Pecola Breedlove, a young black girl who yearned to be loved. Raped by her father, ignored by her mother, she retreats into insanity, believing she is the most loved because she has the bluest eyes, like popular white American cultural icon Shirley Temple. Pecola’s story reflects the complicated construction of self-worth of the black community in the face of dominant white cultural values.

During this time, hard at work as a single mother, Morrison began to develop her short story into the novel The Bluest Eye, which tells the painful story of Pecola Breedlove, a young black girl who yearned to be loved. Raped by her father, ignored by her mother, she retreats into insanity, believing she is the most loved because she has the bluest eyes, like popular white American cultural icon Shirley Temple. Pecola’s story reflects the complicated construction of self-worth of the black community in the face of dominant white cultural values.

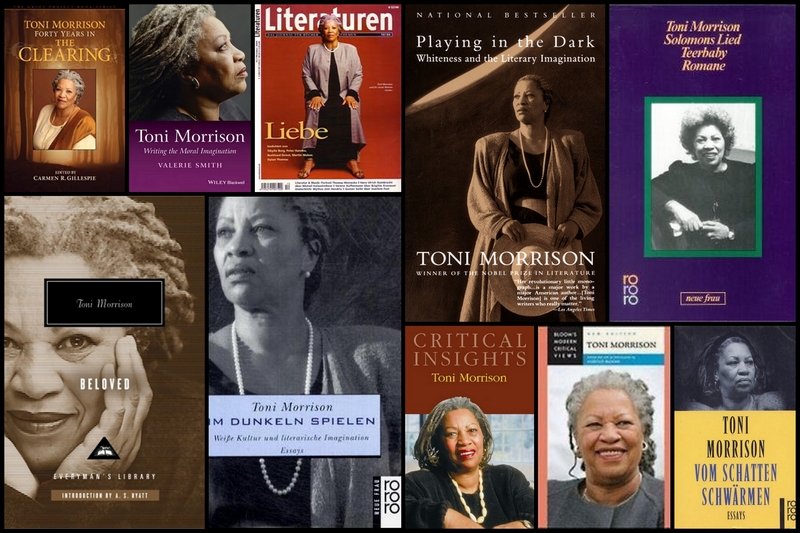

Sula, Morrison's second novel (1973), explores the intense friendship between two contrasting female protagonists whose characters form two halves of one integrated whole: Nel, who conforms unthinkingly to social expectations, and the rebellious pariah Sula. With the publication of Song of Solomon in 1977 Morrison's work achieved popular commercial success, as well as critical acclaim, for this tale of Milkman Dead, whose quest for a legendary family cache of gold leads to his recovery of his family history and his own personal redemption. In 1978 Song of Solomon received Nation Book Critics’ Circle Award for best fiction, making Morrison the first black author since 1940 to receive this award. Tar Baby (1981), an allegorical novel inspired by an African American folktale, treats the division created between black men and women by white society. Pulitzer Prize winning novel Beloved (1987) , through the story of escaped slave woman Sethe who kills her baby daughter rather than see her grow up in slavery, explores the painful history of slavery and the role of the black community in confronting and accepting the past in order to find healing. In Jazz (1992), themes of betrayal, forgiveness, and love are played out against the backdrop of 1920s Harlem, through the experimental device of an unreliable narrator. Playing with the nexus of past and present as in previous works, Paradise (1998), set in an all-black community of former slaves searching for a utopian existence, treats issues of religion, race and slavery, male violence and female rebellion against patriarchy. Morrison's most recent novel Love (2003) depicts the bitter relationships of a group of women whose lives have been touched and damaged by powerful Bill Cosey, the African-American owner of a once-thriving coastal resort.

In addition to her fiction writing, Morrison has also collaborated with her son Slade on three children’s books, The Big Box, based on a story Slade created as a child, The Book of Mean People, a child’s eye view of the world, and Who’s Got Game?, a retelling of Aesop’s Fables.

With her sharp and sensitive vision and mastery of language, Morrison is highly valued as a commentator and critic of literature, arts, issues of race and gender, and American society in general. Her essays have been printed in mass market publications, and Morrison has been invited to visit and lecture at numerous colleges and universities, including her ongoing humanities professorship at Princeton University. Because she wanted “to participate in developing a canon of black work,” her editorial position at Random House was instrumental in guiding and publishing other African American writers, including Toni Cade Bambara, Gayl Jones, Angela Davis, and Henry Dumas. She edited The Black Book (1974), a collection of items that illustrate the history of black life in America over 300 years. In 1992 she published Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagnation, a work of literary criticism about the minimization of the importance of black characters in American Literature, based on a series of lectures at Harvard University.

In 1995, Morrison worked in collaboration with dancer Bill T. Jones and jazz drummer Max Roach on “Degga”, a series of dance performances at New York's Lincoln Center. She was awarded the National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters in 1996, and in that same year was named the Jefferson Lecturer by National Endowment for the Humanities, the highest honor given by the federal government for distinguished intellectual achievement in the humanities.

In 1995, Morrison worked in collaboration with dancer Bill T. Jones and jazz drummer Max Roach on “Degga”, a series of dance performances at New York's Lincoln Center. She was awarded the National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters in 1996, and in that same year was named the Jefferson Lecturer by National Endowment for the Humanities, the highest honor given by the federal government for distinguished intellectual achievement in the humanities.

Reflecting on the significance of the Nobel Prize as a black woman writer, Toni Morrison explained “I felt a lot of “we” excitement… I felt I represented a whole world of women who either were silenced or who had never received the imprimatur of the established literary world… It was very important for young black people to see a black person [succeed]...Seeing me up there might encourage them to write one of those books I'm desperate to read. And that made me happy.” (Morrison: New York Times Magazine)

(2005)

Author: Katherine E. Horsley

Quotes

I would like my work to do two things: be as demanding and sophisticated as I want it to be, and at the same time be accessible in a sort of emotional way to lots of people, just like jazz.

(NYTimes magazine.)

The vitality of language lies in its ability to limn the actual, imagined and possible lives of its speakers, readers, writers.

(Nobel Lecture 12/7/93)

We die. That may be the meaning of our life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.

(Nobel Lecture 12/7/93)

Literature & Sources

Foley, Dylan. “Morrison Takes a Swipe at Societal

Mores in Latest Work.” The Denver Post Nov 16, 2003.

On-line. available:

http://www.lexis-nexis.com/scholastic

“Morrison, Toni.” Current Biography (1979) On-line. H.

W. Wilson Co. Hopkins School Library, New Haven, CT.

15 March, 2005. <http://vnweb.hwwilsonweb.com>

“Morrison, Toni.” Nobel Prize Winners Supplement

1992-1996 (1997) On-line. H. W. Wilson Co. Hopkins

School Library, New Haven, CT. 15 March, 2005.

<http://vnweb.hwwilsonweb.com>

“Morrison, Toni.” World Authors 1975-1980 (1985)

On-line. H. W. Wilson Co. Hopkins School Library, New

Haven, CT. 15 March, 2005.

<http://vnweb.hwwilsonweb.com>

Smith, Dinitia. “Toni Morrison's Mix of Tragedy,

Domesticity, and Folklore.” New York Times Magazine,

Jan 8, 1998. On-line. available:

<http://partners.nytimes.com/library/books/010898toni-morrison-interview.html>

“Toni Morrison.” American Decades 1990-1999. Tandy

McConnell, ed. Gale Group, Inc., 2001.

Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington

Hills, Mich.: Thomson Gale. 2005.

http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/BioRC

“Toni Morrison.” Contemporary Authors Online, Thomson

Gale, 2004. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center.

Farmington Hills, Mich.: Thomson Gale. 2005.

http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/BioRC

“Toni Morrison.” Contemporary Black Biography, Volume

15. Gale Research, 1997.

Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington

Hills, Mich.: Thomson Gale. 2005.

http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/BioRC

“Toni Morrison.” Contemporary Novelists, 7th ed. St.

James Press, 2001.

Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington

Hills, Mich.: Thomson Gale. 2005.

http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/BioRC

“Toni Morrison.” Feminist Writers. St. James Press,

1996.

Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington

Hills, Mich.: Thomson Gale. 2005.

http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/BioRC

“Toni Morrison.” Notable Black American Women, Book 1.

Gale Research, 1992.

Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington

Hills, Mich.: Thomson Gale. 2005.

http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/BioRC

“Toni Morrison.” St. James Guide to Young Adult

Writers, 2nd ed. St. James Press, 1999.

Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington

Hills, Mich.: Thomson Gale. 2005.

http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/BioRC

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.