Fembio Specials Helke Sander

Fembio Special:

Helke Sander

Born 31 January 1937 in Berlin

German film director, author, actress and activist

80th Birthday on 31 January 2017

Biography • Literature & Sources

Biography

“If you think about things, you become radicalized” (Helke Sander in conversation with Renate Fischetti, Gespräch 47). Both politically and artistically, this pioneer of the German women’s movement and of filmmaking has always been far ahead of her time. “She began to examine social structures and political visions consistently from the perspective of women and children and has continued to follow this principle to the present time” (Politeia: HS Einführung). Sander’s challenging, often discomfiting themes, such as women’s “double burden,” the contradictions between political consciousness and personal action, and particularly the long-avoided story of the rapes that followed WW II, attracted both enthusiastic approval and indignant criticism—and often cost her necessary funding. The “radically unconventional” films (Fischetti 36) evolve a new, experimental filmic language and elude simple readings.

When she was eight years old Sander experienced the firestorm in Dresden together with her mother. By the time she graduated from high school and received the Abitur in Remscheid in 1957 she had attended some 15 schools in various cities; she went on to study at the Ida Ehre School for Acting in Hamburg. In 1959 Sander married the Finnish writer Markku Lahtela and moved to Helsinki, where their son Silvo was born, and she studied Germanistics and psychology at the University of Helsinki, also working as a director for the Finnish Workers’ Theater and for television. “She was counted as one of the prominent new directors and was given everything she wanted; that made her uneasy and she fled.”

When she was eight years old Sander experienced the firestorm in Dresden together with her mother. By the time she graduated from high school and received the Abitur in Remscheid in 1957 she had attended some 15 schools in various cities; she went on to study at the Ida Ehre School for Acting in Hamburg. In 1959 Sander married the Finnish writer Markku Lahtela and moved to Helsinki, where their son Silvo was born, and she studied Germanistics and psychology at the University of Helsinki, also working as a director for the Finnish Workers’ Theater and for television. “She was counted as one of the prominent new directors and was given everything she wanted; that made her uneasy and she fled.”

In 1965 Sander returned to the BRD with Silvo, studied from 1966-69 at the German Film and Television Academy in Berlin, and worked on the side as a reporter and translator to feed herself and her son. “I just worked like crazy. And yet I always had only very little money. I couldn’t even go to the movies.” In spite of this she became active in the German Socialist Student Organization (SDS) and helped to found the “Aktionsrat zur Befreiung der Frauen” (Action Council for the Liberation of Women) in January 1968, which started the movement for Kinderläden (shops converted into childcare centers). (In 1971 she would also help to organize the women’s group “Brot und Rosen,” to challenge the idea that widespread use of the birth-control pill was safe for women.) In 1968 she addressed the SDS delegate convention in Frankfurt, declaring that “the private is political” and asking the SDS to support the women’s political agenda. When the men tried to ignore Sander’s demands and return to business as usual, Sigrid Rüger hurled her famous tomato, and the second wave of the German women’s movement was born.

In 1965 Sander returned to the BRD with Silvo, studied from 1966-69 at the German Film and Television Academy in Berlin, and worked on the side as a reporter and translator to feed herself and her son. “I just worked like crazy. And yet I always had only very little money. I couldn’t even go to the movies.” In spite of this she became active in the German Socialist Student Organization (SDS) and helped to found the “Aktionsrat zur Befreiung der Frauen” (Action Council for the Liberation of Women) in January 1968, which started the movement for Kinderläden (shops converted into childcare centers). (In 1971 she would also help to organize the women’s group “Brot und Rosen,” to challenge the idea that widespread use of the birth-control pill was safe for women.) In 1968 she addressed the SDS delegate convention in Frankfurt, declaring that “the private is political” and asking the SDS to support the women’s political agenda. When the men tried to ignore Sander’s demands and return to business as usual, Sigrid Rüger hurled her famous tomato, and the second wave of the German women’s movement was born.

Two films treat the themes of this time: Brecht die Macht der Manipulateure (Break the Power of the Manipulators; 1967/68) and Der subjektive Faktor (1981). Kinder sind keine Rinder (Children are not Cattle; 1969/70) is a documentary about children in a childcare center, and Eine Prämie für Irene (A Reward for Irene; 1971) treats the double exploitation of woman in family and factory. Sander also campaigned against § 218, the anti-abortion law, and made the film Macht die Pille frei? (Does the Pill Liberate Women?) in 1972, together with Sarah Schumann.

In 1973 Sander and fellow director Claudia von Alemann organized the first European women’s film festival in Berlin, with première showings of 40 German films by women. In the following year she initiated Frauen und Film, the “only feminist film journal in Europe,” to analyze sexism in German films and provide a forum where films by women could be discussed; she was involved at the journal as chief editor and author till 1982. According to Sander, the journal allowed her to fight back against the fact that she was given absolutely no film work, “because [she] was a socialist and a feminist” (Fischetti 50). Unfortunately, the dearth of public as well as private funding would continue to impede the work of this uncompromising experimental filmmaker.

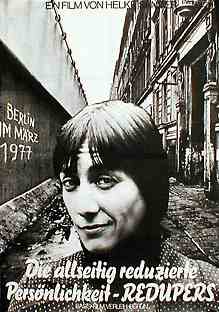

Sander’s first full-length film, Die allseitig reduzierte Persönlichkeit – REDUPERS (The All-Round Reduced Personality—REDUPERS; 1977), shows a gifted woman in Berlin (played by the director) who faces demands from all sides as artist, mother, friend, and public citizen as she and other women struggle to manage their professional, financial, political and personal lives. The film “speaks a new filmic language. It is the first feminist feature film in the BRD” (Fischetti 30), and it received several international prizes. Der subjektive Faktor (1980-81), which deals with the Berlin student movement and the beginnings of the women’s movement, was honored at the Venice Bienniale.

Sander’s first full-length film, Die allseitig reduzierte Persönlichkeit – REDUPERS (The All-Round Reduced Personality—REDUPERS; 1977), shows a gifted woman in Berlin (played by the director) who faces demands from all sides as artist, mother, friend, and public citizen as she and other women struggle to manage their professional, financial, political and personal lives. The film “speaks a new filmic language. It is the first feminist feature film in the BRD” (Fischetti 30), and it received several international prizes. Der subjektive Faktor (1980-81), which deals with the Berlin student movement and the beginnings of the women’s movement, was honored at the Venice Bienniale.

Sander once again played the main role in Der Beginn aller Schrecken ist Liebe (Love is the Beginning of All Terror; 1983/88), in which the story of a man between two women is presented with wit and irony from a female perspective. For the short film Aus Berichten der Wach- und Patrouillendienste – Nr. 1 (Excerpts from Reports of the Guard and Patrol Service – Nr. 1; 1984), about a woman who climbs onto the boom of a gigantic crane with two small children, she was awarded the Golden Bear of the Berlin Film Festival (Berlinale), as well as the Bundesfilmpreis (German National Film Prize) in Silver.

Together with Margarethe von Trotta, Christel Buschmann and Helma Sanders-Brahms Sander produced Felix, a film in episodes, in 1986. The 1989 film Die Deutschen und ihre Männer – Bericht aus Bonn (The Germans and their Men – Report from Bonn), a documentary with fictional elements, investigates the impact of feminist thought after twenty years of women’s activism; male parliamentarians, ministerial officials, the federal Chancellor and the man in the street are all interrogated. (In the film Luise F. Pusch appears as an interviewer and introduces statistics about rape: 330,000 women raped in the Federal Republic each year.) Most of those questioned admit feeling some shame at being German but see no reason to feel shame as a male.

After eight years of research Helke Sander’s BeFreier und Befreite: Krieg, Vergewaltigungen, Kinder (Liberators Take Liberties: War, Rapes, Children; 1991/92) appeared as a two-part documentary film and as a book (co-author: Barbara Johr). For the first time in film the mass rapes at the end of the second World War were seriously confronted; many women are interviewed and have the opportunity to speak for themselves about their trauma and its long-lasting consequences. As usual, Sander was ahead of her time—the film provoked heated discussions in Germany and the USA and was criticized by some as revisionism, while it was praised by others as the successful, long overdue treatment of an important and complex chapter of German history.

After eight years of research Helke Sander’s BeFreier und Befreite: Krieg, Vergewaltigungen, Kinder (Liberators Take Liberties: War, Rapes, Children; 1991/92) appeared as a two-part documentary film and as a book (co-author: Barbara Johr). For the first time in film the mass rapes at the end of the second World War were seriously confronted; many women are interviewed and have the opportunity to speak for themselves about their trauma and its long-lasting consequences. As usual, Sander was ahead of her time—the film provoked heated discussions in Germany and the USA and was criticized by some as revisionism, while it was praised by others as the successful, long overdue treatment of an important and complex chapter of German history.

Krieg und Sexuelle Gewalt (War and Sexual Violence; 1992) reports from refugee camps in Austria and Hungary during the war in Serbia and Bosnia. Muttertier – Muttermensch (Animal Mother – Human Mother; 1998) examines the views of today’s women concerning the maternal role. The film Dorf (Village; 2001) shows how “rural life in the era of globalization … has become an adventure.”

In her latest film Mitten im Malestream (In the Midst of the Malestream; 2005), Sander investigates the history of the second wave of the German women’s movement, its central questions and conflicts, e.g. the politics of motherhood, the campaign for abortion rights against §218, the women’s birth-strike. As is true for her work as a whole, however, this film is more than simply an “illustration” of the phases and issues of the women’s movement. Sander’s films have always owed more to experimental than narrative cinema.

In her latest film Mitten im Malestream (In the Midst of the Malestream; 2005), Sander investigates the history of the second wave of the German women’s movement, its central questions and conflicts, e.g. the politics of motherhood, the campaign for abortion rights against §218, the women’s birth-strike. As is true for her work as a whole, however, this film is more than simply an “illustration” of the phases and issues of the women’s movement. Sander’s films have always owed more to experimental than narrative cinema.

Helke Sander is also active as an author and publicist: Die Geschichten der drei Damen K (The Three Women K), coolly ironic stories about women and men from a feminist perspective (1987), have been translated into five languages. In 1991 the story Oh Lucy appeared, about the “first human,” a woman.

Helke Sander is also active as an author and publicist: Die Geschichten der drei Damen K (The Three Women K), coolly ironic stories about women and men from a feminist perspective (1987), have been translated into five languages. In 1991 the story Oh Lucy appeared, about the “first human,” a woman.

From 1981-2001 Sander was Professor at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste (Academy of fine Arts) in Hamburg. In 1989 she was a co-founder of the Bremen Institute of Film & Television and served as its co-director till 1993. She was elected to the West Berlin Academy of Arts in 1985, from which she later resigned because of “misogyny, nepotism and corruption”. In 2003 she was honored with a retrospective of all of her films in the Arsenal Cinema in Berlin.

***

This is not a complete listing of Helke Sander’s films. More information about her work can be obtained from Cinegraph in Hamburg. Many of the films will be available on DVD in German and English from Neue Visionen in Berlin by February 2007 at the latest. The original films are located in the Stiftung Deutsche Kinemathek / Filmmuseum Berlin, where there is also a rental catalog.

Author: Joey Horsley

Literature & Sources

Helke Sander in the International Movie Database

Helke Sander in the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

Fischetti, Renate. 1992. “'Die Anstrengung besteht im Grunde darin, nicht so festgelegt zu werden…' – Gespräch mit Helke Sander.” In: dies. Das neue Kino – Acht Porträts von deutschen Regisseurinnen. Dülmen-Hiddingsel, Frankfurt/M.: tende. S. 40-59.

Fischetti, Renate. 1992. “Politik und Kunst – Die Filmemacherin Helke Sander. In: dies. Das neue Kino – Acht Porträts von deutschen Regisseurinnen. Dülmen-Hiddingsel, Frankfurt/M.: tende. S. 27-39, 272-276 (Bibliographie).

Helke Sander: Mit den Füßen auf der Erde, mit dem Kopf in den Wolken. Kinemathek Heft 97, Jg. 40 (Oktober, 2003). Freunde der Deutschen Kinemathek e.V., Berlin. 172 S. (Texte von und über Helke Sander; kommentierte Filmographie und Bibliographie)

McCormick, Richard W. 2001. “Rape and War, Gender and Nation, Victims and Victimizers: Helke Sander's BeFreier und Befreite.” Camera Obscura. 16/46. Baltimore, MD. S. 99-141. (Ausführliche, kenntnisreiche Besprechung des Films und der Kontroverse um ihn. Verteidigt den Film gegen die Vorwürfe des Essentialismus, Revisionismus und Reduktionismus)

McCormick, Richard W. 2001. “Rape and War, Gender and Nation, Victims and Victimizers: Helke Sander's BeFreier und Befreite.” Camera Obscura. 16/46. Baltimore, MD. S. 99-141. (Ausführliche, kenntnisreiche Besprechung des Films und der Kontroverse um ihn. Verteidigt den Film gegen die Vorwürfe des Essentialismus, Revisionismus und Reduktionismus)

Sander, Helke. 1991 [1987]. The Three Women K. Transl. Helen Petzold. Serpent's Tail.

Sander, Helke. 1995 [1991]. Oh Lucy: Roman. München. Goldmann.

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.