Fembio Specials Famous Lesbians Claire Waldoff

Fembio Special: Famous Lesbians

Claire Waldoff

(Clara Wortmann (Geburtsname))

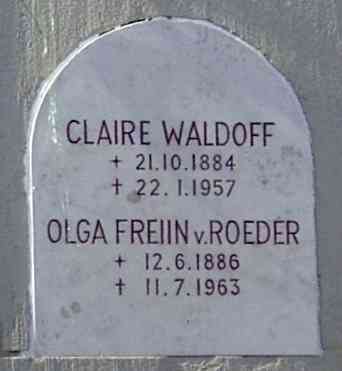

Born 21 October 1884 in Gelsenkirchen

Died 22 January 1957 in Bad Reichenhall

German cabaret performer and singer

60th anniversary of death on 22 January 2017

Biography

Berlin, 1913, in the Linden Cabaret: Head of flaming red hair tipped slightly back, one eyebrow mockingly raised, wearing perhaps a favored gentleman’s tie with her simple blouse – Claire Waldoff sings the song that will become her best-known song, her trademark. Kurt Tucholsky describes her appearance: “Smoothly, mewlingly and innocently she first sings a bunch of things, “if and how and where” – and then suddenly her voice bellows out andante above the heads of the laughing audience and through the cigar smoke and the noise: ‘Hermann heest a ….’ (His name is Hermann …) And once again, softer: ‘Hermann-heest-a…’ And dying away: ‘Hermann-heest-a…’ And on it goes, how he dances and snores and ‘selbst noch im Traume nach mir quäst er… Hermann heest a…!’ (how even in his dream he whines for me). And this piano is so comically studied, so inadequate to the bawling voice that one is stunned. How does she get that piano, that soprano out of herself? A soprano that’s so high that it’s just about to tilt over, G, G sharp, A, B flat…Thank goodness, saved! She sings the way a Berlin sparrow sings, carefree, bold – and then (voice from inside, fading away): ‘Hermann heest a…’”

Claire Waldoff, who is so identified as an Ur-Berliner through and through, as a perky “Bolle” (bold Berlin chick) “mit Schnauze und Herz” (a good-hearted, brash Berliner), was not actually born in the city on the Spree River. She first came to the whirling metropolis in 1906. “Then I saw the gigantic city Berlin for the first time and was overwhelmed. I immediately sensed the special qualities of this town, the incredible tempo, the temperament, the amazing brio,” she writes in her memoir.

Claire Waldoff, who is so identified as an Ur-Berliner through and through, as a perky “Bolle” (bold Berlin chick) “mit Schnauze und Herz” (a good-hearted, brash Berliner), was not actually born in the city on the Spree River. She first came to the whirling metropolis in 1906. “Then I saw the gigantic city Berlin for the first time and was overwhelmed. I immediately sensed the special qualities of this town, the incredible tempo, the temperament, the amazing brio,” she writes in her memoir.

Gelsenkirchen was forgotten – that’s where the miner’s daughter had spent her childhood – forgotten Hanover, where she attended Hedwig Kettler’s high school for girls with the dream of becoming a doctor. And forgotten too was Kattowitz: after her parents’ divorce she could no longer afford to study, but why not make a career out of her love for the theater and music? For two years she played and sang minor roles for provincial and travelling theater companies for a pittance, before succumbing to the magnetic attraction of Berlin, with its theaters and Kleinkunst-stages, the newly popular cabarets.

The novice found at first no regular theater-engagement, only a few minor roles and temporary contracts, and her friends often had to help her out financially. But her name was made after her first performance at the cabaret “Roland von Berlin,” which immediately had new posters printed: “Claire Waldoff, the Star of Berlin.” She had sung only three innocuous little songs (in a dress bought on credit instead of her smart suit, since the official censors forbade women to appear in male clothing after 11 p.m.), but her sassy, comical style, her “winking,” ironic approach even to the most sentimental texts made Claire Waldoff an instant hit and unmistakable star of cabaret. Elegant and simple audiences alike loved their Claire Berolina and laughed at songs such as “Ach Jott, wat sind die Männer dumm” (Oh, God, how stupid men are), “Wer schmeißt denn da mit Lehm” (Who’s throwing mud here?), or “Raus mit den Männern aus dem Reichstag” (Toss out the men from the Reichstag). And they were touched by others such as “Mutterns Hände” (Mother’s hands) or “Das war sein Milljöh” (That was his (Heinrich Zille's) milieu).

The novice found at first no regular theater-engagement, only a few minor roles and temporary contracts, and her friends often had to help her out financially. But her name was made after her first performance at the cabaret “Roland von Berlin,” which immediately had new posters printed: “Claire Waldoff, the Star of Berlin.” She had sung only three innocuous little songs (in a dress bought on credit instead of her smart suit, since the official censors forbade women to appear in male clothing after 11 p.m.), but her sassy, comical style, her “winking,” ironic approach even to the most sentimental texts made Claire Waldoff an instant hit and unmistakable star of cabaret. Elegant and simple audiences alike loved their Claire Berolina and laughed at songs such as “Ach Jott, wat sind die Männer dumm” (Oh, God, how stupid men are), “Wer schmeißt denn da mit Lehm” (Who’s throwing mud here?), or “Raus mit den Männern aus dem Reichstag” (Toss out the men from the Reichstag). And they were touched by others such as “Mutterns Hände” (Mother’s hands) or “Das war sein Milljöh” (That was his (Heinrich Zille's) milieu).

Her rough, unmistakable voice could be heard on the radio and on records; her huge repertoire included music-hall songs, popular Berlin street music, folksongs, operetta melodies, literary chansons. Over a period of three decades she had become a true folk singer.

Claire Waldoff was a thorn in the side of the Nazis. Many of her songs were too bold; many of her composers and lyricists were Jewish, many of her friends rejected National Socialism, as she did. And it was no secret that she lived with a woman…. Under the Nazis many cabarets were closed, many friends went into exile. Claire Waldoff had fewer and fewer appearances and was virtually banned from radio broadcasts. This Berlin was no longer her city, and she seldom appeared there any more, attempting to avoid the constant surveillance by giving guest appearances in other cities.

Claire Waldoff was a thorn in the side of the Nazis. Many of her songs were too bold; many of her composers and lyricists were Jewish, many of her friends rejected National Socialism, as she did. And it was no secret that she lived with a woman…. Under the Nazis many cabarets were closed, many friends went into exile. Claire Waldoff had fewer and fewer appearances and was virtually banned from radio broadcasts. This Berlin was no longer her city, and she seldom appeared there any more, attempting to avoid the constant surveillance by giving guest appearances in other cities.

Claire Waldoff experienced the end of the war with her companion and lover Olly von Roeder in their small Bavarian vacation house. In 1950, already suffering heart problems, she returned one more time, one last time, to her beloved Berlin; one more time she sang the old songs, head of flaming red hair tipped slightly back….

Brigitte Warkus

Addendum concerning Claire Waldoff’s school days in Hanover: Claire Waldoff / Clara Wortmann was a pupil during the opening year (1899) of college-preparatory (Gymnasium) courses for girls which were offered by Hedwig Kettler in Hanover. Kettler had advertised the courses in newspapers. On 8 February 1899 Clara Wortmann wrote as follows to Professor Kettler: “Your school has come to my attention through an advertisement. I intend to study medicine. Would you kindly send me information concerning the situation and conditions there? I am 14 years old, Protestant, and will be confirmed … this year on the 12th of March. I completed the local comparable girls’ school this year and will be glad to send in my grade reports. Would you most kindly inform me if I have a chance of being accepted by your Gymnasium; if so my father will see to the necessary steps.”

In Hanover Clara Wortmann lived with the family Schmitz, the parents of stage and film actor and director Theo Lingen. Presumably she moved there directly in 1899.

Source: Ehrich, Karin: “‘Wie vieler Augen waren auf sie gerichtet.’ Die ersten Abiturientinnen in Hannover.” In: Adlige, Arbeiterinnen und ...: Frauenleben in Stadt und Region Hannover vom 17. bis zum 20. Jahrhundert. Hg. Karin Ehrich und Christiane Schröder. Bielefeld 1999. Verlag für Regionalgeschichte. S. 131-157.

Barbara Fleischer trans. Joey Horsley

For sources and links see the German version.

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.