Fembio Specials Women from North and South Tyrol and the Trentino Anna Ladurner Hofer

Fembio Special: Women from North and South Tyrol and the Trentino

Anna Ladurner Hofer

born 27 July 1765 in Algund near Merano

died 6 December 1836 in St. Leonhard in Passeier

Innkeeper and wife of the Tyrolean freedom fighter Andreas Hofer

185th anniversary of death on December 6, 2021

Biography

She was the wife of a national hero, mother of seven children; during the long years of her husband’s absence she maintained and financially restored the debt-laden inn that he had taken over; she wangled a pension and a title of nobility from the Emperor a few months after her husband had been executed. Her tombstone – which was erected only decades after her death during the 1909 centenary of the Tyrolean struggle for liberation on Mount Isel near Innsbruck – identifies her by her maiden name: “Anna Ladurner, Andreas Hofer’s wife.” They had left off the title “Edle (Noblewoman) von Hofer” – supposedly because she was controversial in the valley community into which she, a stranger, had married. If the historical tradition of 1809 recognized two main female types, one the militant, courageous woman who reached for her pitchfork and rifle, the other the sensitive motherly one, then Anna Ladurner Hofer should be located somewhere in the middle:

She was no Katharina Lanz, who repelled the French in 1797 standing on the cemetery wall of Spinges with her pitchfork and became an inspiration to many women. She was not Gretele of Thin, who defended Latzfons together with other brave young women. She never stood at his side in battle, as did Anna Zorn, Elisabeth Pichler and Marie Hofer and other women who gave cover to Andreas Hofer and his men with hay wagons. She was no Giuseppina Negrelli from Primör, who – at 18 years of age – fought in men’s clothes and tossed an enemy soldier into the Inn River. Rather, she is to be found among the anonymous heroines.

She was no Katharina Lanz, who repelled the French in 1797 standing on the cemetery wall of Spinges with her pitchfork and became an inspiration to many women. She was not Gretele of Thin, who defended Latzfons together with other brave young women. She never stood at his side in battle, as did Anna Zorn, Elisabeth Pichler and Marie Hofer and other women who gave cover to Andreas Hofer and his men with hay wagons. She was no Giuseppina Negrelli from Primör, who – at 18 years of age – fought in men’s clothes and tossed an enemy soldier into the Inn River. Rather, she is to be found among the anonymous heroines.

••••••••••••••••••_ There are few written documents pertaining to Anna Ladurner. Parish registers testify to her birth, marriage and death; the notice of her birth is located in Algund near Merano. As was customary at the time, she was baptized on the day of her birth, July 27th, 1765.

On the 27th day Anna, the legitimate daughter of the reputable married couple Peter Ladurner, “’Rinner’ in Mitterplars und Bauer beim Zenz”, and Maria Tschölin, was christened by the honorable Mr. Christian Kolfer, while Francisca Tschölin held the child.

Anna was the fourth of eleven children; her father came from a respected branch of the Ladurner family, wine and fruit growers with their own family crest.

Nothing is known about her childhood and adolescence; they will have been the way childhood and adolescence were at the time: an extended family living together in a large group, life shaped by faith and work. In the face of disease, epidemics, unplanned pregnancies and the ravages of war, popular piety and its diverse religious practices played a large role; moreover, between 1718 and the turn of the century some 1200 missionarizing campaigns were conducted in Tyrol. Thus a fundamental religiosity had taken hold there as probably nowhere else in the Habsburg empire. It was out of such an orientation that the Capuchin father Joachim Haspinger appealed to the population to resist vaccination against smallpox when it had been ordered by the Bavarian administration, even though almost one third of the children died from the feared pox. He argued that it was not humanity’s place to meddle in God’s plan in this way.

The fact that Anna Ladurner was very religious was attested to several times; she had that in common with her husband. It often helped her in her difficult life.

Where she met Andreas Hofer is not known. Possibly he had come to her father’s farm as a horse and wine dealer. Or perhaps they had met each other at a church festival where he impressed her with his “Robeln” (fighting skills). The local historian and author Beda Weber writes that Hofer was victorious over the tallest farmers at fist-fighting, and that his relationship with Anna was very heartfelt.

She was a sensible, loyal woman of few words but deep emotions. She felt the greatest tenderness for her husband. Some people took her reserved nature to be a sign of arrogance, others thought she was melancholy, but she was neither. A quiet, earnest manner has been a mark of her family to the present day.

The second documented event in Anna Ladurner’s life was her marriage. One can read about it in the record books in St. Leonhard, where Anna Ladurner and Andreas Nikolaus Hofer celebrated their wedding on July 21st, 1789. The bride was 24, the bridegroom 21; both were thus relatively young.

For three years the marriage remained childless, for which Anna would probably have been teased. Finally, in 1792, Maria Gertraud was born; she did not survive infancy. The second child would be the only son, Johann Stephan. He was followed by five more daughters, Maria Kreszenz, Rosa Anna, Anna Gertraud, Gertraud Juliana and Kreszenz Margareth. The last girl was born amid the turmoil of war in 1808; like her sister she died as a young child.

For three years the marriage remained childless, for which Anna would probably have been teased. Finally, in 1792, Maria Gertraud was born; she did not survive infancy. The second child would be the only son, Johann Stephan. He was followed by five more daughters, Maria Kreszenz, Rosa Anna, Anna Gertraud, Gertraud Juliana and Kreszenz Margareth. The last girl was born amid the turmoil of war in 1808; like her sister she died as a young child.

As an innkeeper Anna Ladurner had a special position from the very beginning; that she meant more to her husband than simply being the children’s mother was clear from the letters he wrote her. He reported to her on the progress of the battles and sent her messages to be forwarded secretly. When, as a highly decorated Tyrolean senior commander, he resided in Innsbruck, she stayed home with the children, the inn, the work. And much later, when he was buried for a second time with pomp and honors in the Court Church of Innsbruck, she did not attend the ceremonies.

When he was defeated at the fourth battle of Mount Isel, and hostile French troops invaded the land via the Passeier Valley, Andreas Hofer sent his wife and children to a hiding place on the Schneeberg in December 1809, while he fled himself to the Mähder hut on the Pfandler Alm at 1400 meters elevation, above St. Martin in Passeier. Around the 24th of December, however, Anna left her daughters with friends and followed him to the hut with their son Johann – consciously and self-confidently. Tradition has it that the time at the hut was a time of deprivation: they barely dared light a fire, lest the enemy in the valley should notice them; there was almost nothing to eat; the most they could do was pray. When Hofer was betrayed and captured at four o’clock on the morning of January 28, she accompanied him – bound herself – down to the valley. It is not known whether she was allowed to put shoes on; later she was said to have gotten medical treatment for her feet several times. The fifteen-year-old son lost toes and for the rest of his life could only hobble. On January 30 Anna was released from the St. Afra jail in Bolzano, following efforts of Bolzano townswomen on her behalf. She was permitted to return to the pillaged Sandhof (their inn), and civil and military authorities were given orders to protect her. Son Johann was admitted to a military hospital. Andreas Hofer was executed on February 20th in Mantua.

When shortly thereafter bankruptcy proceedings were initiated for the Sandhof, she wasted no time, packed her bags and set off for Vienna, determined to see Emperor Franz I. She arrived in Vienna on the evening of July 22nd, 1810 with a pass from Bolzano and stayed (incognito as Anna Ladurnerin) with a compatriot in Vienna’s Josephstadt No. 47. Senior police detective Strobel reported by July 24th on her arrival and noted that Anna Hofer intended first to attend to her defective feet – damaged during her capture? – and then to seek an audience with the Emperor.

The historian Granichstaedten-Czerva gives a thorough description of her visit in Vienna. She attracted disapproval, primarily because she openly wore the traditional Passeier dress, and raised eyebrows especially with the hat. That could have proven embarrassing for Emperor Franz I, who had married his daughter Marie Louise to Napoleon just three months earlier. And Bonaparte had personally given the order to shoot the rebel Andreas Hofer.

The historian Granichstaedten-Czerva gives a thorough description of her visit in Vienna. She attracted disapproval, primarily because she openly wore the traditional Passeier dress, and raised eyebrows especially with the hat. That could have proven embarrassing for Emperor Franz I, who had married his daughter Marie Louise to Napoleon just three months earlier. And Bonaparte had personally given the order to shoot the rebel Andreas Hofer.

Her third audience, on September 2nd, 1810, seems to have brought her what she wanted, and she departed five days later. He gave her 2000 Gulden in bank notes and 800 Gulden in cash, together with the prospect of a lifelong pension: 500 Gulden for her, and 200 for each of the daughters. And she was promised a title of nobility, Edle von Hofer – which however she was only granted some years later, in 1818, once Napoleon had been defeated and banished.

From then on she resided at the Sandhof, which was free of debt as of 1816. The author Franz Tumler found that for every house destroyed by fire the owner was granted 50 Gulden; each family whose provider had been killed received 30 Gulden. She won many times these amounts from the Emperor.

Anna Ladurner was later required to appear in court to face charges of embezzlement; the official hearing record is (besides her birth, marriage and death records and the secret police report from Vienna) the only non-fictional documentation of her life. She was able to produce papers that proved that chests of money had been in part incorrectly distributed, in part falsely alleged to have been hers. She signed the document with an X; we don’t know whether she could read and write or not.

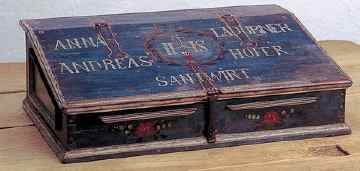

Relatively soon after Andreas Hofer’s death, in November 1810, the Bavarian crown prince Ludwig visited the Sandhof and asked Anna Ladurner Hofer to tell him about her husband. Ever more tourists and travel writers came to view the objects that had belonged to him. Anna herself, said to have lived a modest and quiet life, never boasted about the heroic deeds of her husband.

Late in her life all four daughters died within four years; of her seven children only her son survived her. “Fräulein Anna von Hofer” is the last entry, directly above her mother’s name in the death records of St. Leonhard; she was 34, her mother 72. Anna Ladurner died only eight days after her daughter on St. Nicholas’ Day, 1836. She decreed in her will that the Sandhof should be taken over by her granddaughter Anna Erb for 9000 Gulden payment. She also left an endowment providing for a mass to be held each year on November 30th for her and her husband’s souls.

(trans. Joey Horsley)

Author: Astrid Kofler

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.