(Pamela Lyndon Travers OBE (née Helen Lyndon Goff, Helen "Ginty" Lynwood Goff))

born August 9, 1899, Maryborough, Queensland, Australia

died April 23, 1996, London, England

Australian writer, drama critic, student of myths, author of Mary Poppins books

120th birthday on August 9, 2019

Biography • Weblinks • Literature & Sources

Biography

“Myth has been my study and joy ever since the age . . . of three.

The true fairytales … come straight out of myth. One might say that

fairytales are the myths falling into time and locality.”

Recently I asked a friend if she were a fan of Mary Poppins. “Oh yes!” she replied, “that was a great movie!” – referring to the 1964 Disney movie of that title. “Did you like the books?” I asked. “Books? What books?” she wondered.

My friend wasn’t alone. Apparently some people who know and love the movie are not familiar with the six books of stories about the mysterious nanny that inspired it – one of the most popular and successful in American film history – nor with their author, P. L. Travers. Even less well known is the fact that Travers, in addition to writing her Mary Poppins books, was a serious student of myths and fairy tales, and wrote and spoke extensively about them in different cultures – Australian, Celtic, Native American, Indian – and their meaning in our lives.

Childhood in Australia

Born in 1899 in the Australian bush in Maryborough, Queensland, P. L. Travers started life as Helen Lyndon Goff. Her mother, Margaret Agnes Morehead Goff, was Australian, the sister of the former Premier of Queensland. Her father, Travers Robert Goff, was born in London, England. He was of Irish descent and felt a strong affinity for Ireland and its culture. He worked as a bank manager, but because of his alcoholism, he was demoted to bank clerk. He died when Travers was seven. She then moved with her mother and two younger sisters to Bowral, New South Wales, where they lived for ten years with an eccentric great aunt, Helen Morehead, later Christina Saraset. During World War I Travers attended a boarding school near Sydney.

Born in 1899 in the Australian bush in Maryborough, Queensland, P. L. Travers started life as Helen Lyndon Goff. Her mother, Margaret Agnes Morehead Goff, was Australian, the sister of the former Premier of Queensland. Her father, Travers Robert Goff, was born in London, England. He was of Irish descent and felt a strong affinity for Ireland and its culture. He worked as a bank manager, but because of his alcoholism, he was demoted to bank clerk. He died when Travers was seven. She then moved with her mother and two younger sisters to Bowral, New South Wales, where they lived for ten years with an eccentric great aunt, Helen Morehead, later Christina Saraset. During World War I Travers attended a boarding school near Sydney.

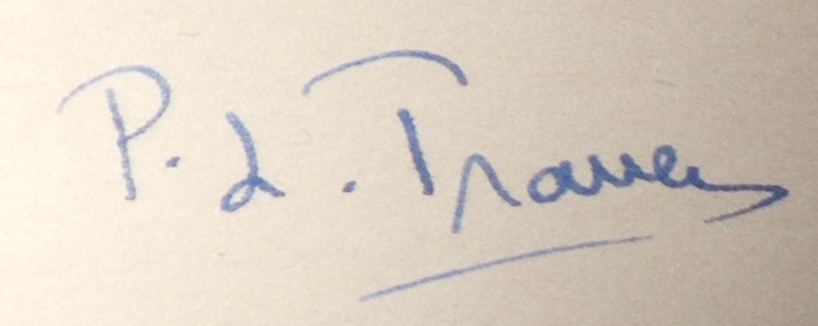

Both Travers’s parents had literary inclinations and exposed her and her sisters to many books and tales during her childhood. She began writing poems at a young age, and as a teenager had some success in getting them published. She also tried her hand as an actress; she took the name Pamela Lyndon Travers, with her father’s first name as her surname. She joined a Shakespearean acting company and went on tours in Australia and New Zealand. But she always felt drawn to England and Ireland, and was impatient to leave Australia and travel to those countries. In 1924, at age 25, she did so, returning to Australia only once, much later.

Writer in England and Ireland

Travers settled in London with some Morehead relatives. She worked as a drama critic for several publications. She also sent a poem to George William Russell (also known as AE, writer, mystic, and editor of The Irish Statesman). She was astonished when he not only accepted it, but sent her some money and asked her for more poems. AE, known for his generosity to young writers, took Travers under his wing and became something of a father figure and literary mentor to her. Through him she also met W. B. Yeats, the poet and mystic, as well as George Gurdjieff, a well known Russian mystic whose spiritual teachings and writings came to mean a great deal to her. These men and others became Travers’s spiritual “gurus,” inspiring her to develop her ideas about myths and fairy tales and their relevance to contemporary life. She pursued these interests throughout her life; in 1960 she traveled to Japan to study Zen Buddhism.

Travers settled in London with some Morehead relatives. She worked as a drama critic for several publications. She also sent a poem to George William Russell (also known as AE, writer, mystic, and editor of The Irish Statesman). She was astonished when he not only accepted it, but sent her some money and asked her for more poems. AE, known for his generosity to young writers, took Travers under his wing and became something of a father figure and literary mentor to her. Through him she also met W. B. Yeats, the poet and mystic, as well as George Gurdjieff, a well known Russian mystic whose spiritual teachings and writings came to mean a great deal to her. These men and others became Travers’s spiritual “gurus,” inspiring her to develop her ideas about myths and fairy tales and their relevance to contemporary life. She pursued these interests throughout her life; in 1960 she traveled to Japan to study Zen Buddhism.

Personal Life

Travers is said to have had “numerous fleeting relationships” with men. She also had a long-term, possibly romantic relationship with Madge Burnand, the daughter of Sir Francis Burnand, playwright and former editor of Punch magazine. They lived together for more than ten years, starting in 1927 when they shared a flat in London and later in a small thatched cottage called Pound Cottage in Mayfield, Sussex in the south of England. Travers never married, but in 1939, when she was 40, she adopted a twin baby boy from Ireland. She named him Camillus Travers Hone (Hone was his grandfather’s surname), and she did not tell him he had a twin brother. But when Camillus was seventeen, his brother Anthony tracked him down. Despite Travers’s refusal to let them see each other, they did get together, although they had little in common besides a liking for alcohol. Camillus was very bitter for a long time. But in later years he mellowed and visited Travers from time to time with his wife and their children – her grandchildren.

Travers is said to have had “numerous fleeting relationships” with men. She also had a long-term, possibly romantic relationship with Madge Burnand, the daughter of Sir Francis Burnand, playwright and former editor of Punch magazine. They lived together for more than ten years, starting in 1927 when they shared a flat in London and later in a small thatched cottage called Pound Cottage in Mayfield, Sussex in the south of England. Travers never married, but in 1939, when she was 40, she adopted a twin baby boy from Ireland. She named him Camillus Travers Hone (Hone was his grandfather’s surname), and she did not tell him he had a twin brother. But when Camillus was seventeen, his brother Anthony tracked him down. Despite Travers’s refusal to let them see each other, they did get together, although they had little in common besides a liking for alcohol. Camillus was very bitter for a long time. But in later years he mellowed and visited Travers from time to time with his wife and their children – her grandchildren.

World Travels

Beginning in the 1930s Travers made several trips abroad. She visited Russia in 1932, and two years later published her first book, Moscow Excursion, having taken the pen name P. L. Travers. During World War II she worked for the British Ministry of Information. When bombs began falling in the Mayfield area, many children were being evacuated. In the summer of 1940, Travers and Camillus, along with about three hundred children, boarded a ship for Canada. She took responsibility for children from Mayfield and Tunbridge Wells. During the voyage, Travers did some writing, eventually completing several short books that she later sent to friends as Christmas gifts. One, Aunt Sass, tells the story of her eccentric great aunt with whom she and her mother and sisters had lived for ten years in Australia, and on whom the character Mary Poppins is said to be partly based.

Beginning in the 1930s Travers made several trips abroad. She visited Russia in 1932, and two years later published her first book, Moscow Excursion, having taken the pen name P. L. Travers. During World War II she worked for the British Ministry of Information. When bombs began falling in the Mayfield area, many children were being evacuated. In the summer of 1940, Travers and Camillus, along with about three hundred children, boarded a ship for Canada. She took responsibility for children from Mayfield and Tunbridge Wells. During the voyage, Travers did some writing, eventually completing several short books that she later sent to friends as Christmas gifts. One, Aunt Sass, tells the story of her eccentric great aunt with whom she and her mother and sisters had lived for ten years in Australia, and on whom the character Mary Poppins is said to be partly based.

Travers and Camillus settled in New York. While in America for the duration of the war, Travers met with a friend, John Collier, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. He arranged for Travers to travel to the southwest and spend some time with Navajo, Pueblo, and Hopi Indians. She came to appreciate many of their cultural ways, especially their affinity for meditative silence. They appreciated her as well; the Navajo gave her a secret Indian name, which they said she must never divulge to anyone. She never did.

The Mary Poppins Books

While convalescing from a lung ailment in the early 1930s, Travers began telling stories about a magical nanny to two children. She was inspired by the works of other writers of fiction such as James Barrie, Beatrix Potter, A. A. Milne, and Lewis Carroll. These stories would become the seeds of the books for which she was to become most famous, featuring the mysterious nanny Mary Poppins. She wrote them – plus two related books – over a span of more than fifty years, between 1934 and 1988. Although they are usually considered children’s books, Travers stated that “I never wrote for children.” Rather, she insisted, children “have been kind enough to read what I write.” Further, she claimed, “I have always assumed…that [Mary Poppins] had come out of the same well of nothingness as the poetry, myth and legend that had absorbed me all my writing life.”

While convalescing from a lung ailment in the early 1930s, Travers began telling stories about a magical nanny to two children. She was inspired by the works of other writers of fiction such as James Barrie, Beatrix Potter, A. A. Milne, and Lewis Carroll. These stories would become the seeds of the books for which she was to become most famous, featuring the mysterious nanny Mary Poppins. She wrote them – plus two related books – over a span of more than fifty years, between 1934 and 1988. Although they are usually considered children’s books, Travers stated that “I never wrote for children.” Rather, she insisted, children “have been kind enough to read what I write.” Further, she claimed, “I have always assumed…that [Mary Poppins] had come out of the same well of nothingness as the poetry, myth and legend that had absorbed me all my writing life.”

The stories are about the rather dysfunctional Banks family who live at 17 Cherry Tree Lane in 1930s London. The father is a banker who goes off to work each day in a sullen mood to “make money.” Mrs. Banks, a flustered housewife and mother, is at her wits’ end trying to run her household and take care of her four – soon five – children. Jane and Michael, about seven and six respectively, are the oldest, followed by toddler twins John and Barbara, and eventually by baby Annabel.

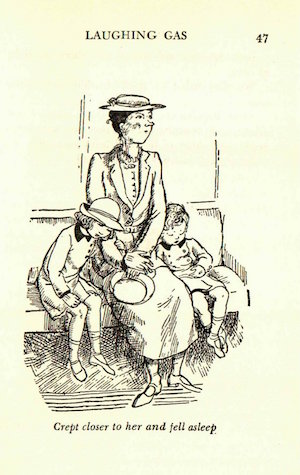

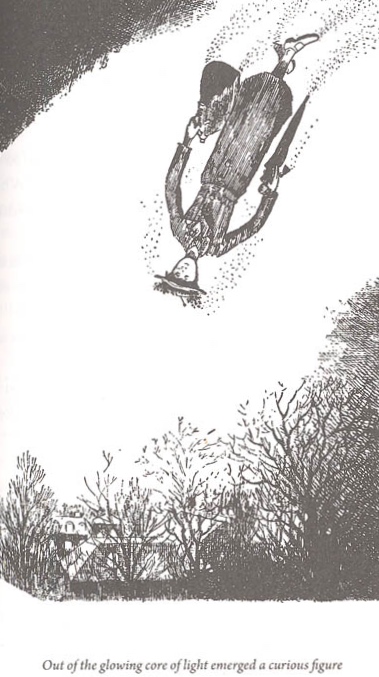

Mrs. Banks is clearly in need of help to put some order into this family chaos. Mary Poppins, the new nanny, arrives mysteriously on an east wind. She is strict but kind, vain but not pretty – the books’ illustrator, Mary Shepard (daughter of E. H. Shepard, who illustrated the Winnie the Pooh books), modeled her on a plain wooden Dutch doll! Through a combination of firm rules and genuine affection – often concealed by her stern demeanor – and her dry humor and wit, Mary Poppins soon gains the children’s trust and love.

In addition, she takes them on numerous adventures beyond the bounds of the everyday, such as journeys into the sky and beneath the ocean, where they converse with stars and planets and sea creatures as if such escapades were hardly extraordinary. Jane and Michael also find that they can communicate with a marble statue of a boy in a nearby park; Jane joins a group of boys who are part of the decoration on a Royal Doulton bowl. After such experiences, Mary Poppins denies that they occurred. But usually a tell-tale bit of evidence proves to the children that they really did happen, as when Mary Poppins’s scarf appears later on the side of the bowl, left when she had to go into the bowl to rescue Jane.

These and other similar adventures, entertaining as they are, are more than mere flights of fancy. They embody some of P. L. Travers’s serious thinking about the nature of the cosmos and how human beings relate to it. For instance, she considers that an infant, during the first year of his or her life, sees the world as undifferentiated and doesn’t distinguish objects clearly from each other; and understands the language of elemental qualities such as the wind and rain, and of animals. The young child lives by “a cosmography of wonder.” But after a year, all that changes as the “chattering mind” takes over and one’s early sense of connectedness is forgotten as we fall into an extended sleep. (Developing this idea much later – possibly inspired by the teachings of Gurdjieff and other mystical writers with whose works she was familiar – Travers suggests that we are all trying to wake from that extended sleep, like that in the fairy tale “The Sleeping Beauty,” to find our forgotten, authentic selves.)

Travers expresses this idea in the story “The New One” (in Mary Poppins Comes Back). When a starling asks the infant Annabel, lying in her cradle, where she came from, she understands the question and replies:

Travers expresses this idea in the story “The New One” (in Mary Poppins Comes Back). When a starling asks the infant Annabel, lying in her cradle, where she came from, she understands the question and replies:

“I am earth and air and fire and water….I come from the Dark where all things have their beginning….I come from the sea and its tides.…I come from the sky and its stars, I come from the sun and its brightness….Slowly I moved at first…always sleeping and dreaming. I remembered all I had been, and I thought of all I shall be. And when I had dreamed my dream I awoke and came swiftly.”

But by the time Annabel’s teeth have come in a year later and the starling tries to speak with her again, she’s unable to do so, having lost that intimacy with the cosmos.

Another story, “Happy Ever After” (in Mary Poppins Opens the Door), takes place on New Years Eve. Before Mary Poppins puts the children to bed, Michael wants to know what happens after the end of the old year and before the beginning of the new one – between the first and last strokes of midnight. She doesn’t answer, but she leaves several of the children’s stuffed animals out on top of the toy-cupboard, and leaves three of their story books open in front of the animals. Later, on the Big Ben clock’s first stroke, the children awake and find themselves outside in the park, in the “Crack” in time between the first and last stroke. Their toy animals have come alive, along with many familiar characters from their story books. Many who in the tales are “eternal opposites,” such as the lion and the lamb, Red Riding Hood and the wolf, “meet and kiss” and dance together in what Travers dubs the “Happy Ever After.” But on the last stroke of midnight, they part from each other again and vanish. As one reviewer put it, Travers depicts “a Crack in space-time, in which anything is possible and all problems disappear.” Later she was to describe this possibility of reconciliation as “the homeland of myth.”

Another story, “Happy Ever After” (in Mary Poppins Opens the Door), takes place on New Years Eve. Before Mary Poppins puts the children to bed, Michael wants to know what happens after the end of the old year and before the beginning of the new one – between the first and last strokes of midnight. She doesn’t answer, but she leaves several of the children’s stuffed animals out on top of the toy-cupboard, and leaves three of their story books open in front of the animals. Later, on the Big Ben clock’s first stroke, the children awake and find themselves outside in the park, in the “Crack” in time between the first and last stroke. Their toy animals have come alive, along with many familiar characters from their story books. Many who in the tales are “eternal opposites,” such as the lion and the lamb, Red Riding Hood and the wolf, “meet and kiss” and dance together in what Travers dubs the “Happy Ever After.” But on the last stroke of midnight, they part from each other again and vanish. As one reviewer put it, Travers depicts “a Crack in space-time, in which anything is possible and all problems disappear.” Later she was to describe this possibility of reconciliation as “the homeland of myth.”

The Mary Poppins books were extremely popular. Besides being entertaining and stimulating to the imagination, they sensitized readers to the wonder and mystery of existence, advising them not to take anything for granted, and to question everything – but not necessarily to expect answers. The frequent reference to astronomical phenomena led one biographer to note that Mary Poppins “brought the cosmos into Cherry Tree Lane.” (Draper and Koralek, p. 21) Dancing features in several stories, often with earthly and astronomical beings joining hands in a celebratory “Grand Chain.” In the story “Christmas Shopping,” Maia, one of the stars in the Pleiades constellation, comes down to earth and joins Mary Poppins and the children to buy presents for her starry sisters.

The Disney Movies

Three of Travers’s Mary Poppins books had been published by the early 1940s when American filmmaker Walt Disney heard his eleven year old daughter laughing over them. She told him it would be wonderful if he could make a movie based on the books. Disney took her wish to heart, and for nearly twenty years he tried, unsuccessfully, to persuade Travers to let him do so. Travers kept refusing; she considered his earlier movies based on fairy tales to be overly sentimental and lacking in subtlety. Finally, however, largely for financial reasons, she relented. She insisted on being a consultant, but when she traveled to the Disney studios in 1961, she had many quarrels with the filmmakers. She was dissatisfied with some of the casting. She bristled at the suggestion of a romantic relationship between Mary Poppins and Bert the match man. She was also vehemently opposed to the use of any animation in the movie. (She was assured there would not be any; but in the end, there was.)

The movie “Mary Poppins” came out in 1964. Although it was wildly successful – it received thirteen Academy Award nominations and won five – some critics deplored its profound differences from the books. In particular, critics frowned on its portrayal of Mary Poppins as a charming “soubrette” (flirt) – unlike the prim and proper character in the books, who would hardly be seen doing the cancan on a rooftop, revealing her underwear. Some considered the movie superficial and saccharine, and that it “drained the character of her very essence.” Others regretted its abandonment of cosmological themes that come through in the books. One reviewer, watching the movie a generation later, suspected that children in the audience were being “cheated of the real thing.”

Travers herself was deeply disappointed by the movie. It was billed as “Walt Disney’s Mary Poppins,” with Travers’s name appearing only in small type in the opening credits. It is true that the movie made her very wealthy, and that after seeing it, some people started to read the books. But Travers’s relationship with Disney had become so chilly that she was not even sent an invitation to the premier showing of the movie. Finally an embarrassed executive sent her one; she did go, and was reduced to tears. One of Travers’s biographers described the movie as “designed to highlight the singing, dancing and comedic skills of Julie Andrews, Dick Van Dyke, and an acrobatic ensemble,” as well as the talents of its animators. (Demers, p. 81) The director of the New York Public Library stated, “the acerbity of Mary Poppins, unpredictable, full of wonder and mystery, becomes, with Mr. Disney’s treatment, one great marshmallow-covered cream puff.” (Lawson, p. 276) Eventually Travers – who had befriended Julie Andrews – conceded that it was a good movie in and of itself, but was very different from the book.

Travers herself was deeply disappointed by the movie. It was billed as “Walt Disney’s Mary Poppins,” with Travers’s name appearing only in small type in the opening credits. It is true that the movie made her very wealthy, and that after seeing it, some people started to read the books. But Travers’s relationship with Disney had become so chilly that she was not even sent an invitation to the premier showing of the movie. Finally an embarrassed executive sent her one; she did go, and was reduced to tears. One of Travers’s biographers described the movie as “designed to highlight the singing, dancing and comedic skills of Julie Andrews, Dick Van Dyke, and an acrobatic ensemble,” as well as the talents of its animators. (Demers, p. 81) The director of the New York Public Library stated, “the acerbity of Mary Poppins, unpredictable, full of wonder and mystery, becomes, with Mr. Disney’s treatment, one great marshmallow-covered cream puff.” (Lawson, p. 276) Eventually Travers – who had befriended Julie Andrews – conceded that it was a good movie in and of itself, but was very different from the book.

Two more movies based on Mary Poppins stories followed. “Saving Mr. Banks,” which Walt Disney Pictures released many years later in 2013, dramatizes the fraught relationship between Travers and Disney in the making of the 1964 movie. Starring Emma Thompson as Travers and Tom Hanks as Disney, it met with mixed responses from reviewers, with some noting that Travers was portrayed as more curmudgeonly, and Disney more saintly, than either was in real life. Then in 2018 “Mary Poppins Returns,” a sequel to the 1964 movie, was released, with Emily Blunt playing the lead. This time, Mary Poppins’s young charges have grown to adulthood, with children of their own; and Michael – a widower in financial trouble – is in need of Mary Poppins’s attention once more. Again, reviews were mixed; but all three movies won many honors.

Writer in Residence

Travers spent the college semesters in the autumn of 1965 and 1966 as a writer in residence at two colleges for women in the United States – Radcliffe in Cambridge (part of Harvard) and Smith in Northampton, both in Massachusetts. A few years later, in 1970, she was again a writer in residence at Scripps College in Claremont, California. Although some students found her distant and idiosyncratic, many came to sit at her feet to hear her speak about myth and poetry and fairy tales, always encouraging the students to ask questions. While at Radcliffe she also took advantage of the riches of Harvard’s Widener Library, researching versions of her favorite tale, Sleeping Beauty, in several cultures. She would later publish these in a book, About the Sleeping Beauty.

Travers spent the college semesters in the autumn of 1965 and 1966 as a writer in residence at two colleges for women in the United States – Radcliffe in Cambridge (part of Harvard) and Smith in Northampton, both in Massachusetts. A few years later, in 1970, she was again a writer in residence at Scripps College in Claremont, California. Although some students found her distant and idiosyncratic, many came to sit at her feet to hear her speak about myth and poetry and fairy tales, always encouraging the students to ask questions. While at Radcliffe she also took advantage of the riches of Harvard’s Widener Library, researching versions of her favorite tale, Sleeping Beauty, in several cultures. She would later publish these in a book, About the Sleeping Beauty.

Writings on Myths and Fairy Tales

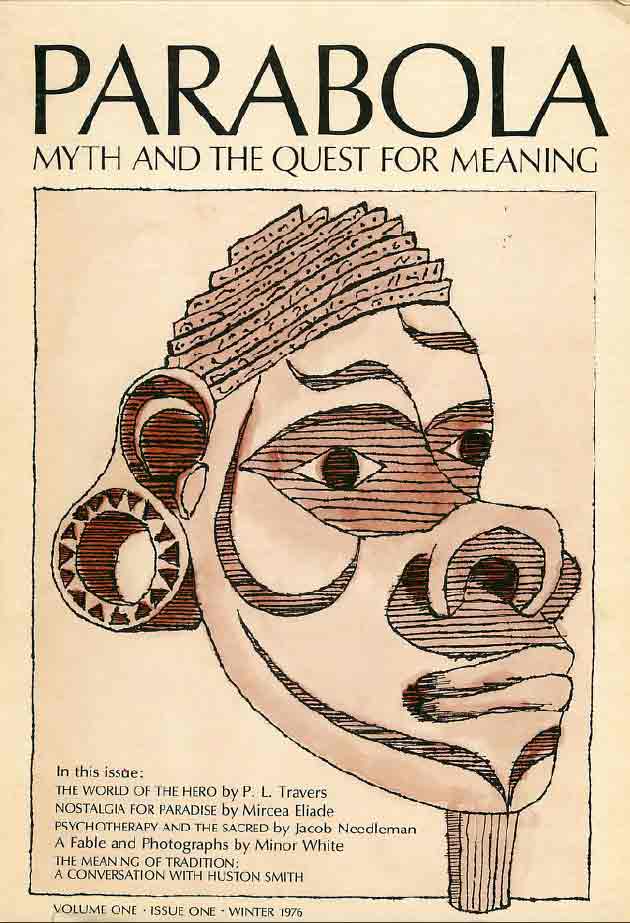

In 1976, Travers and a friend, D. M. Dooling – also a writer and follower of Gurdjieff – co-founded a journal called Parabola, a Magazine of Myth and Tradition to explore myths and ancient spiritual traditions. Each issue was planned to focus on a universal theme, such as memory or death. Travers wrote more than forty essays for the journal. She served as a consulting editor as well. Many of her essays, interviews, and poems are collected in a book titled What the Bee Knows: Reflections on Myth, Symbol, and Story (the bee being understood as a symbol of eternal life), published in 1989. The book is a feast of her writings in this area, setting forth her ideas in lively, often captivating prose as she delves deep into various topics. One reviewer on amazon.com, highly enthusiastic, nevertheless cautioned, “Each chapter is fortunately short – they are so rich it’s like a box of chocolate truffles – eat one and it’s heaven – eat more and it's too much.”

Travers’s essay for the first issue of Parabola is “The World of the Hero.” She sets the tone by asserting, “We go to the myths not so much for what they mean as for our own meaning. Who am I? Why am I here? How can I live in accordance with reality?” The hero in myths and tales, she writes, is seeking his/her own identity; and in life, each of us is the hero of our own myth. Recalling her concept of the “Crack” between the first and last strokes of midnight on New Years Eve when “eternal opposites meet and kiss,” she goes on: “I have to set out to find the homeland of myth, that homeland so well described in ‘Rumpelstiltzkin’ where it is called ‘the country where the fox and the hare say goodnight to each other’…where the opposites are reconciled, the place where one goes beyond them….I wonder where we can find it, where in ourselves we can look for it?”

Travers’s essay for the first issue of Parabola is “The World of the Hero.” She sets the tone by asserting, “We go to the myths not so much for what they mean as for our own meaning. Who am I? Why am I here? How can I live in accordance with reality?” The hero in myths and tales, she writes, is seeking his/her own identity; and in life, each of us is the hero of our own myth. Recalling her concept of the “Crack” between the first and last strokes of midnight on New Years Eve when “eternal opposites meet and kiss,” she goes on: “I have to set out to find the homeland of myth, that homeland so well described in ‘Rumpelstiltzkin’ where it is called ‘the country where the fox and the hare say goodnight to each other’…where the opposites are reconciled, the place where one goes beyond them….I wonder where we can find it, where in ourselves we can look for it?”

In her essay “The Primary World”, Travers recalls her childhood as a place of lore and legend that her parents encouraged. Religious writings as well as “stories, ballads, and old wives tales” handed down to her felt close; “Heaven was merely a celestial suburb.” Daily life tended to imitate them: “The smallest event, in that huge landscape, became, of necessity, an occasion. To take a trip to the nearest town…was to ride in triumph to Persepolis [an ancient Persian city]; the loss of a milk tooth no less an omen than the dropping of Cinderella’s slipper.” This idea that we live out myths in the events of our lives reverberates through many of her essays.

Another essay, “About the Sleeping Beauty,” is a reprint of a chapter in her book of the same title. She muses, “I shall never know which good lady it was who, at my own christening, gave me the everlasting gift…of love for the fairy tale.” “Thinking is linking,” she frequently stated, here linking her own childhood with the Sleeping Beauty tale. Elsewhere in Bee, in an essay titled “The Fairy Tale as Teacher,” she writes, “the fairy tales are like water-flowers; they lie so lightly on the surface, but their roots go down deep into a dark and ancient past. They are, in fact, a remnant of that Orphic art whose function it was to instruct the generations in the inner meanings of things.” (Draper and Koralek, p. 202)

Travers discouraged approaching a fairy tale from an academic, analytical standpoint, but felt that one should “let it drop into you like a stone” – preferably by listening to someone tell it rather than reading it. She was particularly critical of Bruno Bettelheim’s interpretation of Sleeping Beauty as being about “nothing but” the onset of menstruation, insisting that “nothing is ever nothing but.” Rather, as she writes in “The World of the Hero,” “The myths never have a single meaning, once and for all and finished. They have something greater; they have meaning itself. If you hang a crystal sphere in the window it will give off light from all parts of itself. That is how the myths are; they have meaning for me, for you and everyone else. A true symbol has always this multisidedness. It has something to say to all who approach it.”

Later Years

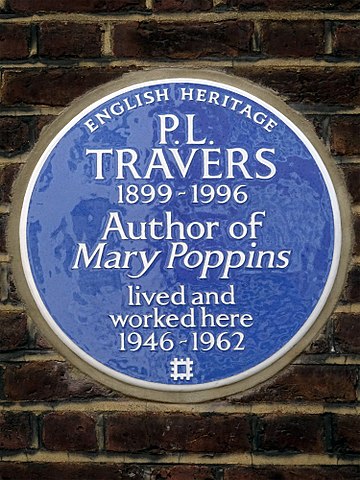

Travers continued to write for Parabola. After a gap of thirty years since her fourth book of Mary Poppins stories was published in 1952, in 1982 Travers published a fifth one; and in 1988, a sixth, her last. Despite the fact that she was plagued at different times throughout her life by various ailments, often gastrointestinal, she was very prolific and is highly regarded for her contributions to literature. In 1977 she was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire.

Travers continued to write for Parabola. After a gap of thirty years since her fourth book of Mary Poppins stories was published in 1952, in 1982 Travers published a fifth one; and in 1988, a sixth, her last. Despite the fact that she was plagued at different times throughout her life by various ailments, often gastrointestinal, she was very prolific and is highly regarded for her contributions to literature. In 1977 she was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire.  The following year she received an honorary doctorate in humane letters from Chatham College, a small women’s college in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

The following year she received an honorary doctorate in humane letters from Chatham College, a small women’s college in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

As Travers grew older, she became increasingly withdrawn, living for seventeen years in a house in Chelsea and seeing few people. A private person for most of her life, she shunned interviewers and biographers, reluctant to disclose details of her past. In 1996 Travers died of an epileptic seizure at the age of 96. Her last essay from Parabola in What the Bee Knows is titled “Only Connect,” E. M. Forster’s epigraph to his novel Howard’s End. These words, she had long felt, summed up her concept of our need to find meaning in our lives by relating them to the wisdom of the ages in myth and tale.

Author: Dorian Brooks

Links

Please note: not all links listed here have been evaluated for their veracity or accuracy. Please refer to the Literature and Sources section for reliable material used in the biographical essay.

PL Travers, The Real Mary Poppins - Part 1 of 6. Video references the 2004 musical, not discussed in the Fembio biography.

Barlass, Tim. 2014-01-05. The truth behind Mary Poppins creator P.L. Travers. The creator of Mary Poppins was practically imperfect.

Online: https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/movies/the-truth-behind-mary-poppins-creator-pl-travers-20140104-30akz.html (last downloaded 2019-02-26)

Brockes, Emma. 2018-11-23. Mary Poppins: why we need a spoonful of sugar more than ever. The Emily Blunt reboot reintroduces PL Travers’ nanny for uncertain times but is she a feminist?

Online: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2018/nov/23/mary-poppins-why-we-need-a-spoonful-of-sugar-more-than-ever (last downloaded 2019-02-26)

Dooley, Ian. 2016-01-22. More than Mary Poppins: The Archive of P.L. Travers and Mary Shepard at Cotsen Children’s Library.

Online: https://blogs.princeton.edu/cotsen/2016/01/more-than-mary-poppins-the-archive-of-p-l-travers-and-mary-shepard-at-cotsen-childrens-library/ (last downloaded 2019-02-26)

Inge, M. Thomas. 2012. P. L. Travers, Walt Disney, and the Making of Mary Poppins. Palack´y University, Olomouc.

Online: https://moravianjournal.upol.cz/files/MJLF0302Inge.pdf (last downloaded 2019-02-26)

Revtai, Donna M. 1997. The domestic Sybil: Feminist concerns in P. L. Travers's “Mary Poppins” and “Mary Poppins Comes Back”. Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters.Thesis (M.A.)Florida Atlantic University.

Online: http://fau.digital.flvc.org/islandora/object/fau%3A12727/datastream/OBJ/view (last downloaded 2019-02-26)

Mandanas, Laura. 2014-13-01. “Saving Mr. Banks” Erases P.L. Travers’ Queer Identity, Misses Amazing Opportunity for Representation.

Online: https://www.autostraddle.com/saving-mr-banks-erases-p-l-travers-queer-identity-misses-amazing-opportunity-for-representation-216786/ (last downloaded 2019-02-26)

The Secret Life of Mary Poppins: A Culture Show Special. BBC. (07.12.2013, Molly Ipek)

Ellen. 2014-02.13. Pamela Lyndon Travers.

Online: https://reveriesunderthesignofausten.wordpress.com/2014/02/13/pamela-lyndon-traverswomanwriterchildrensbooks/ (last downloaded 2019-02-26)

Picardie, Justine. 2008-10.28. Was P L Travers the real Mary Poppins? The Telegraph.

Online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/donotmigrate/3562643/Was-P-L-Travers-the-real-Mary-Poppins.html (last downloaded 2019-02-26)

P.L. Travers Biography. Encyclopedia of World Biography.

Online: https://www.notablebiographies.com/supp/Supplement-Sp-Z/Travers-P-L.html (last downloaded 2019-02-26)

Edmund, Aiyana. 2018-04-19. P.L. Travers. Literary Ladies Guide. Inspiration for Readers and Writers from Classic Women Authors.

Online: https://www.literaryladiesguide.com/author-biography/travers-p-l/ (last downloaded 2019-02-26)

Biography.com Editors. 2014-04-02. P.L. Travers Biography.

Online: https://www.biography.com/people/pl-travers-21358293 (last downloaded 2019-02-26)

The Mary Poppins Effect. New perception of P.L. Travers and her mythical creation.

Online: https://themarypoppinseffect.com (last downloaded 2019-02-26)

The Real Mary Poppins -Mary Poppins Documentary. (27.12.2017, Timeline)

Literature & Sources

Patricia Demers, P. L. Travers (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1991)

Eller Dooling Draper and Jenny Koralek, eds., Lively Oracle: A Centennial Celebration of P. L. Travers, Creator of Mary Poppins (New York: Larson Publications, 1999)

Giorgia Grilli, Myth, Symbol, and Meaning in Mary Poppins: the Governess as Provocateur (New York and London: Routledge, 2007)

Julia Kunz, Intertextuality and Psychology in P.L.Travers’s Mary Poppins Books. (Frankfurt am Main and New York. Peter Lang Edition, 2014)

Valerie Lawson, Mary Poppins, She Wrote (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999)

Sharyn M. Peare, The business of myth-making: Mary Poppins, P.L. Travers and the Disney effect. Queensland Reviw, 22(1), pp. 62-74.

Online: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/93153/9/93153.pdf (last downloaded 2019-02-26)

P. L. Travers, About the Sleeping Beauty (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1975)

___________, Aunt Sass: Christmas Stories (New York and Boston: Hachette Books, 2014)

___________, the Mary Poppins books – six collections of stories, plus two related books:

- Mary Poppins (London: Collins, 1934)

- Mary Poppins Comes Back (London: Collins, 1935)

- Mary Poppins Opens the Door (London: Collins, 1943)

- Mary Poppins in the Park (London: Collins, 1952)

- Mary Poppins in Cherry Tree Lane (London: Collins, 1982)

- Mary Poppins and the House Next Door (London: Collins, 1989)

- Mary Poppins from A to Z (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1962)

- Mary Poppins in the Kitchen: A Cookery Book with a Story (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975)

___________, What the Bee Knows: Reflections on Myth, Symbol and Story (London: Penguin Books, 1989)

Also, numerous interesting essays in a current online blog: https://themarypoppinseffect.c

om/

om/

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.