(geb. Reizes)

(née Reizes)

born 30 March 1882 in Vienna

died 22 September 1960 in London

Austrian–English psychoanalyst, "Mother of Psychoanalysis"

60th anniversary of death 22 September 2010

Biography • Quotes • Weblinks • Literature & Sources

Biography

Psychoanalysis could be described in the first half of the 20th century as relating to the founder of the discipline, Sigmund Freud, as if he were an authoritarian father. At least he was seen that way by many, although this is undoubtedly a caricature. However, the second half of the 20th confirmed Melanie Klein as the psychoanalyst whose impact on both the theoretical framework of psychoanalysis, as well as its clinical practice, remarkably has been as great as that of the 'father' of psychoanalysis. Should we then think of her as the 'mother' of psychoanalysis?

It was Klein’s extraordinary ability to enter into the world of very young children that brought us the whole new concept of the existence of an internal world.

Born in Vienna of Jewish parentage, she was the youngest child of four. In 1910 she married and moved to Budapest where she went into an analysis with Sandor Ferenczi, becoming a psychoanalyst herself in her 30’s. She had wanted to do a medical training but her father’s early death prevented this. At the age of 38, separated from her husband and on her own with small children, an asylum seeker from the anti-Semitism in Budapest, she moved to Berlin, the most exciting psychoanalytic centre of the time. She had little money and few friends but believed that her interest in child psychoanalysis would be welcomed. In her unpublished autobiography she said, ‘My interest in children’s minds goes back a very long way. I remember that even as a child of eight or nine I was interested in watching younger children. I was wildly keen on knowledge, and deeply ambitious.’ She persuaded (pleaded with) Karl Abraham to take her into analysis and, impressed by her work with children, he was soon proclaiming: ‘The future of psychoanalysis rests with child analysis.’

In a sense, Kleinian thinking began in Berlin. There she began the series of analyses of children that were to become the basis of her newly found method on which she built her psychoanalytic thinking. The children were as young as 2 , and her reports of these analyses met with much hostility, especially in Berlin, but also stimulated great interest, particularly in England. After Abraham’s sudden death in 1925, she felt isolated and unsupported in Berlin and by the end of 1926 she had emigrated to London where she spent the rest of her life.

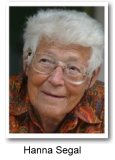

All agreed she was a formidable presence. Very beautiful when young, Hanna Segal reports she was known as ‘The black beauty’. Alix Strachey who befriended Klein in Berlin and was immensely impressed by her psychoanalytic creativity, described her as “hearty, very direct and surprisingly ‘naïve’ for someone with such subtle analytic understanding.”

All agreed she was a formidable presence. Very beautiful when young, Hanna Segal reports she was known as ‘The black beauty’. Alix Strachey who befriended Klein in Berlin and was immensely impressed by her psychoanalytic creativity, described her as “hearty, very direct and surprisingly ‘naïve’ for someone with such subtle analytic understanding.”

According to Hanna Segal, her close friend and follower in London, Klein was passionate about discovering human nature. That insatiable interest led to her interest in literature. She was irresistibly drawn to the classics, Russian, French and English. She was also fond of theatre and of music. She played the piano and attended concerts whenever possible, classical music being her favourite. She liked a good laugh, she liked wine. She even once won a wine tasting competition in the South of France—-a rare achievement for a woman. Although her image was of someone quite dour, she was extremely sociable, enjoying a good party and was even quite flirtatious until her very old age.

On the other hand, Melanie Klein experienced a lot of tragedy throughout her life. When she was 4 her 8 year old sister, said to be mother’s favourite, died. ‘I have the feeling that I never entirely got over the feeling of grief for her death.’ And indeed Klein suffered from episodes of depression throughout her life. In her 20’s, the brother to whom she was extremely close died. And she experienced the sudden loss of her second analyst, Abraham, when he died soon after she started analysis with him. She also lost a son, possibly through suicide, and eventually her daughter turned against her in the most publicly violent way. As well as having to uproot from her homeland, she had much to contend with in her professional life with all the rivalries and intense hostility towards her ideas.

Klein was something of an iconoclast within a profession dominated by medically trained men. Her early collaborators were women and the contribution of women analysts to this school has remained important to the present day. As Michael Rustin points out, there are few theoretical advances in the social sciences, apart from feminism itself, of which this can be said. (1991) Kleinian theory does give enormous emphasis to the mothering role—about which the Women’s Movement sometimes had ambivalent feelings.

After having written a number of articles on her work, in 1932 Klein published The Psychoanalysis of Children, which was almost immediately recognized as one of the most original psychoanalytic contributions to date. Where Freud proposed a model of the mind with clearly differentiated structures and stages of development, Klein presented a much more dynamic set of processes in which a number of emotions and developmental levels operated simultaneously and with tumultuous intensity—‘a mosaic of turbulence’ (Grosskurth). Early in her work she began to use small toys and came to consider the play of children equivalent to free association of adults. In the child’s play she witnessed violent phantasies which were accompanied by acute anxiety.

It was Melanie Klein’s thinking about and imagining what was happening inside her child patients that transformed our understanding of human experience and gave a reality to the idea of an internal world. She almost immediately began to hear things from these children about spaces and particularly about a very special space that was inside themselves in their bodies in a very concrete way and inside their mothers' bodies in particular. By listening to her child patients she discovered that in our minds we live in an internal as well as an external world and that the internal world, from which our dreams are created, is as real and alive as the external one. The idea that we were relating to internal objects that were alive in our minds, rather than merely relics from the past, changed dramatically our understanding of states of mind and our view of major psychoanalytic concepts.

As Donald Meltzer described it, if Freud had been able to develop the concept of an inner world he could have leapt forward the way Melanie Klein’s work leapt forward the moment she discovered that children were preoccupied with the inside of their mothers’ bodies and that it was really a place, a world in which life was going on. It took somebody like Mrs Klein, listening to little children talking about the inside of the mother’s body with absolute conviction as if it were Budapest or Vienna as an absolutely geographical place, to realise that there really is an inner world and that it is not just allegorical or metaphorical, but has a concrete existence—in the life of the mind. (1978)

Her emphasis on the experience of ambivalence, on the contradictory feelings of the child, the love and the hate felt toward the mother, led to a whole new understanding of the development of the mind and the importance of the mother/infant dynamic.

Kleinian theory also offers a distinctively uncompromising view of human destructiveness, and the continuing and unavoidable problem in human lives of coping with this. The omnipresence of envy is perhaps one distinguishing emphasis of Kleinian understanding of human experience. Klein’s developmental theory, in which attaining maturity means reaching what she calls the ‘depressive position’, is of huge importance in the external world where polarization and discrimination abound. The ‘depressive position’ arises from the recognition of the pain suffered by, or inflicted on, the other. Individuality is shown to be not the starting point but rather the emergent result of a prolonged and delicate process of dependency. Similarly, concern for the well-being of the other is seen as the result of a struggle with a state of mind in which the other is alien. (Klein came to call this the paranoid-schizoid position.) As the depressive position is reached (though never finally achieved), there are experiences of guilt and remorse for attacks on one’s objects (the others) in the paranoid-schizoid position.

Despite the ongoing controversies which her theories provoked, she continued to work, surrounded by devoted colleagues, until she died at 78. She was, even in her 70’s, a handsome woman, fond of big hats and dressing well. She lived alone with a maid and a visiting secretary and her cat in a fair sized first floor flat in Hampstead, on a hill with views. According to Hanna Segal, she was extremely vigorous with a remarkable memory. Right to the end she never missed a meeting. She had lots of friends but she did feel lonely and quite often depressed. Her last paper was in fact on loneliness as a lifelong reality, but also the special plight of old age. However, she delighted in having grandchildren, the children of her son Erich, and she was working to the end.

Author: Mary Adams

Quotes

Sie ist ein bisschen übergeschnappt, das ist alles. Es gibt aber keinen Zweifel daran, dass ihr Geist übersprudelt von sehr, sehr interessanten Dingen. (Alix Strachey, Übersetzerin von Psychoanalyse des Kindes, gefunden hier)

Links

The Melanie Klein Trust. Enthält u.a. biografische Informationen, Fotos und Bibliografie. (Link aufrufen)

Berlin.de (2008): Gedenktafel für Melanie Klein. (Link aufrufen)

Goddemeier, Christof: 50. Todestag von Melanie Klein: Pionierin der Kinderanalyse. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt, 10.09.2010. (Link aufrufen)

Gondek, Hans-Dieter (2002): Streit um die Phantasie. Die Kontroverse Anna Freud – Melanie Klein. Buchbesprechung. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 3. Januar 2002. (Link aufrufen)

Google-Buchsuche: Melanie Klein. (Link aufrufen)

Kuhl, Walter (1999): Das Frauenbild in der Psychoanalyse – Melanie Klein. Manuskript einer Sendung auf Radio Darmstadt am 22. März 1999. (Link aufrufen)

Psychoanalytikerinnen. Biografisches Lexikon. Melanie Klein geb. Reizes (1882-1960). Biografie und Auswahlbibliografie. Bitte Eintrag über das Register auswählen. (Link aufrufen)

Voos, Dunja: Melanie Klein und die »Kleinianer«. Kurze Darstellung der Kleinianischen Theorien. medizin-im-text. (Link aufrufen)

Bitte beachten Sie, dass verlinkte Seiten im Internet u. U. häufig verändert werden und dass Sie die sachliche Richtigkeit der dort angebotenen Informationen selbst überprüfen müssen.

Letzte Linkprüfung durchgeführt am 01.10.2010 (AN)

Literature & Sources

For additional information please consult the German version.

The collected Writings of Melanie Klein, London: Hogarth Press. Volume 1 - Love, Guilt and Reparation: And Other Works 1921-1945 Volume 2 -The Psychoanalysis of Children Volume 3 -Envy and Gratitude Volume 4 -Narrative of a Child Analysis, Claudia Frank, Melanie Klein in Berlin: her first psychoanalyses of children, tr. Sophie Leighton and Sue Young, Routledge New Library of Psychoanalysis 2009 Phyllis Grosskurth, Melanie Klein: Her World and Her Work, Alfred A Knopf, Inc. 1986 Robert Hinshelwood, A Dictionary of Kleinian Thought, Free Association Books 1989 Robert Hinshelwood, Clinical Klein, Free Association Books 1993 Mary L Jacobus, The Poetics of Psychoanalysis: In the Wake of Klein, Oxford University Press, 2006 Julia Kristeva, Melanie Klein, tr. Ross Guberman, Columbia University Press, 2001 Meira Likierman, Melanie Klein: Her Work in Context, Continuum, 2001 Monique Lauret et Jean-Philippe Raynaud, Melanie Klein, une pensée vivante, Presses Universitaires de France, 2008 Donald Meltzer, The Kleinian Development, Karnac Books, 1978 Jacqueline Rose, Why War?—Psychoanalysis, Politics, and the Return to Melanie Klein, Blackwell Publishers, 1993 Michael Rustin, The Good Society and the Inner World, Verso, 1991 Janet Sayers, Mothering Psychoanalysis: Helene Deutsch, Karen Horney, Anna Freud, Melanie Klein, London; Hamish Hamilton, 1991 Hanna Segal, Klein, Karnac Books, 1989 Julia Segal: (1992). Melanie Klein. London: Sage. Elizabeth Spillius, ed. Melanie Klein Today Vol I & II Developments in Theory and Practice Routledge, 1988

Melanie Klein was the subject of a 1988 play by Nicholas Wright, entitled Mrs. Klein. Set in London in 1934, the play involves the conflict between Melanie Klein and her daughter Melitta Schmideberg, after the death of Melanie's son Hans Klein. The play was broadcasted on the British radio station BBC 4 in 2008 and revived at the Almeida Theatre in London in October 2009.

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.