(Marie Julia Paneth (Fuerth) )

Born August 15 1895 in Sukdull (near Wurzing), Austria

Died November 30, 1986 in the Hazlewell nursing home in Putney

Austrian-British artist, pioneering child therapist and writer

125th birthday August 15th, 2020

Biography • Weblinks • Literature & Sources

Biography

In 1945, three months after Germany and Austria were occupied by Allied Forces, 300 Jewish children (many Polish) were brought from concentration camps to a school by the shores of Lake Windermere in the UK. They are known as the Windermere Children, about whom a very moving BBC dramatized documentary has been made. In photos of the group, one notices a tall beautiful woman. This was Marie Paneth, then 50, an artist, art therapist and writer, and herself a Jewish exile born in Austria.

The newly liberated children were flown over on Sterling bombers to Carlisle and Marie Paneth was there to receive them. In preparation for the arrival a staff of around 35 had repurposed a set of barracks built during the war for aircraft factory workers:

They had scrubbed and rescrubbed the dormitories. The beds had crisp white sheets. Little bowls of sweets had been placed on the nightstands. The staff wanted the children to feel welcome, but none knew quite what to expect of these children who had been found in or near the liberated ghetto-camp of Theresienstadt in Czechoslovakia.

They knew little about what had gone on in Hitler’s concentration camps, but had all seen shocking photos in newspapers and footage in newsreels of the liberation of Bergen-Belsen and Buchenwald in April 1945: the corpses of the dead, and the starved and broken bodies of the living, peering out of skull-like faces, witnesses to conditions so horrific they stretched the human imagination. An estimated 90% of Europe's Jewish children were killed in the Holocaust. The children due to arrive that afternoon had seen the inside of the concentration camps. How would they behave? What would they need? Would the staff at Windermere be able to help them at all?

Expecting the children to be very young, the staff went around placing dolls and teddy bears on the beds. Then they waited for the planes. The hours crept by. The first plane arrived at around 4pm. The assembled crowd pressed forwards: staff, journalists from the local papers, customs officials and a welcoming party from the local Women’s Voluntary Service. But to the surprise of those waiting, the children who stepped off the plane were teenagers. Plane after plane arrived, but there were no young children among the passengers….Finally, long after dark, the last two planes arrived, and among the passengers were nine children between the ages of four and ten, and six three-year-old toddlers. (Goldberger)

We are indebted to Marie Paneth for her own detailed accounts of her extraordinary work with young children both in Windermere and previously in the slums of London. She was highly sophisticated psychologically, full of intelligent questioning and self-reflection.

To give a sense of the passion with which she worked, I quote from her description of the Windermere children:

Snatched from the cremation kilns, saved from the firing squad, stolen from the “sleeping shelves” of Theresienstadt and Auschwitz, 450 Jewish children landed in England a few days after Berlin was occupied. Were they children indeed? Their ages were those of children, but their sizes were puny, and their minds so twisted, parcelled and mutilated that they behaved only with the predictability of wild and hunted beasts. Insane? Perhaps. Psychopathic? Certainly. Permanently? We didn’t think so, and because we didn’t think so we worked to rebuild those shattered lives.

On the gentle shores of Lake Windermere, one of England’s most beautiful, the busses arrived late at night with 300 of these children. As the busses spilled them into our arms they were talking. Talking, talking, talking, a frenzy of talking horror. They had lived a cadenza of horror that would have finished off any of us, and it was as if they wanted to give us their credentials by talking. It was a nightmare. There was no stemming the flood. Excitedly, but unemotionally, they rattled off their tales, while without the slightest unruliness they did what they were told: undressed, were inspected by the doctors, waited, had baths, went to bed. (Paneth, 1946)

She describes how carefully the staff worked together, developing ways to gain the children’s trust and bring a sense of normality and safety into their lives. One example of her acute perception was her realisation that while in the concentration camps the children’s belief in any future had been wiped out—-they had learned not to plan and not to hope. In Windermere, the staff would talk through with them plans for the next day—-but nobody turned up! It was as though any image of a future had to be blocked. Paneth also describes how plagued with guilt each child was, guilt they had survived and regrets they hadn’t acted differently in the camps.

In the Windermere Children documentary, some of those still alive convey how life-saving and important their time at Windermere had been. It was a mere four months, but with dedication, insight and constant discussion and reflection, the staff were able to transform the lives of these children. They were led by a brilliant psychiatrist, Oscar Friedman (1903-1958), himself a German-Jewish survivor of the camps, [see Winnicott 1959 obituary] who, along with Paneth and Alice Goldberger (1897-1986), the former superintendent at Anna Freud’s Hampstead Nurseries [see M. Friedmann 1986 obituary by Winnicott], believed that more than anything the children needed freedom to develop their own way of thinking. Paneth ascribed the fact that no major disaster occurred there to this lack of pressure and the resulting atmosphere of ease: “None of the boys or girls committed suicide in these critical weeks; none killed any other; nobody got seriously ill; nor were there any serious accidents. On the other hand, the straightforward outspokenness of their conversations with us showed their trust in the sanity of their surroundings.” (1946: 54)

“It was paradise,” said one of the children. “There were boys in a pair of underpants and a vest, running about in the streets!” “We weren’t guarded, we were free,” said another. “It was a wonderful time for us. We really started living in Windermere - slowly.”

The six under-fives who had survived Theresienstadt came to Windermere with no sense of the world before the war. “I had no clothes of my own, no toys, no possessions, no passport, no parents, no family,” said one. “I barely knew who I was.” They were kept together and formed a family. “If one had a nightmare, we didn’t go to the grown-ups; it was always one of us that would help out. We really were totally self-sufficient, even at that age.” Observations of the children were sent to Anna Freud, a long-term friend of Marie Paneth, who continued to work with the six youngest children after they left Windermere and who published a detailed study in 1951. Anna Freud’s later work on child development was very much influenced by the Windermere children. [See: https://www.thetcj.org/child-care-history-policy/an-experiment-in-group-upbringing-by-anna-freud-and-sophie-dann]

Before she came to England, Marie Paneth had already led a very full life. From the age of five she lived in Vienna and crucial to her later work with children was her early training under the renowned and revolutionary Austrian painter and educationalist Franz Cizek (1865-1946). This was an exciting and experimental time in the art world and Cizek, a friend of Gustav Klimt, became famous for his art classes with underprivileged children encouraging improvisation and complete freedom of expression. Stefan Zweig described Austrian education in 1900 as relentlessly rigid: “Every detail was supervised by the Ministry of Religion and Education. The spirit was authoritarian.” There is much written on the subordination of women artists at that time—-in 2019 the Belvedere Museum in Vienna curated an exhibition, The Forgotten Women Artists of Vienna 1900—-but Cizek and Klimt seem to have been among the more progressive thinkers and practitioners:

Officially women remained barred from membership in the male artists’ leagues…and fought a long and bitter battle to gain admission to the Academy of Fine Arts (1920/21). The major exception was the Klimt Group’s progressive attitude towards including the art of women—and even children (for example, Franz Cizek’s influential Jugendkunstkurse at the School of Applied Arts). (Johnson, 2012.)

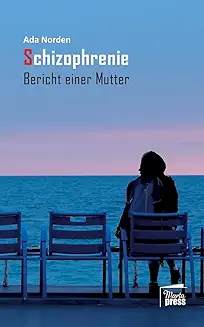

Cizek offered classes free of charge for any child between the ages of two and fourteen, but was most happy when the children were two to three years of age: “This is the age of the purest art, when the child expresses what is in him.” Paneth was clearly greatly influenced by Cizek’s teaching and maintained the courage of her conviction in this anti-authoritarian approach. It allowed her to persevere in working with the most deprived and difficult children in London during the war. As she describes in her book Branch Street, the local children completely destroyed the first project she set up, but when given responsibility to develop their own play centre in a bombed-out building, they were highly creative, developing a place complete with playground and a self-managed cafe. Sadly, her book Branch Street is hard to come by now and used mainly by art therapists, but it is a brilliant, lively and very moving study. It was published already in 1944 and reviewed in the Observer by no less than George Orwell:

Cizek offered classes free of charge for any child between the ages of two and fourteen, but was most happy when the children were two to three years of age: “This is the age of the purest art, when the child expresses what is in him.” Paneth was clearly greatly influenced by Cizek’s teaching and maintained the courage of her conviction in this anti-authoritarian approach. It allowed her to persevere in working with the most deprived and difficult children in London during the war. As she describes in her book Branch Street, the local children completely destroyed the first project she set up, but when given responsibility to develop their own play centre in a bombed-out building, they were highly creative, developing a place complete with playground and a self-managed cafe. Sadly, her book Branch Street is hard to come by now and used mainly by art therapists, but it is a brilliant, lively and very moving study. It was published already in 1944 and reviewed in the Observer by no less than George Orwell:

A valuable piece of sociological work has been done by Mrs Marie Paneth. …For nearly two years Mrs Paneth has been working at a children’s play centre…When she first went there the children were little better than savages. In behaviour they resembled the troops of ‘wild children’ who were a by-product of the Russian civil war. They were not only dirty, ragged, undernourished and unbelievably obscene in language and corrupt in outlook, but they were all thieves, and as intractable as wild animals.

... The boys simply smashed up the play centre over and over again, sometimes breaking in at night to do the job more thoroughly.

...It took a long time for this gentle, grey-haired lady, with her marked foreign accent, to win the children’s confidence. The principle she went on was never to oppose them forcibly if it could possibly be avoided, and never to let them think that they could shock her. …During the last war she worked in a children’s hospital in Vienna and later in a children’s play centre in Berlin. She describes the ‘Branch Street’ children as much the worst she has encountered in any country…but with certain redeeming traits: the devotion which even the worst child will show in looking after a younger brother or sister.

…The surprise which this book caused in many quarters is an indication of how little is still known of the underside of London life. …It would be difficult to read the book without conceiving an admiration for its author, who has carried out a useful piece of civilising work with great courage and infinite good-temper. (13 August 1944.)

The descriptions of the children’s abject living conditions caused a stir in the English press and became a matter of national concern. Orwell himself demanded an investigation of the effect of war and evacuation on the welfare of children, but sadly public opinion seemed far from sympathetic to these children, calling them ‘thugs’ and a threat to democracy. [Kozlovsky, 2013]

The 2020 Tom Stoppard play, Leopoldstadt, is a moving portrayal of the Vienna Paneth grew up in. Her father, Alfred Fuerth, died suddenly in 1899 at the age of 40 when Marie was only four. Her mother, also Marie, was left with four young children but supported by her own relatives, the Jeitteles, a prominent Jewish family in Bohemia. Her mother lived until she was 80 and her siblings all emigrated.

Before her forced emigration to England at the end of 1939, Marie had lived in a number of different countries. During WWI she married an Austrian doctor, Otto Paneth, with whom she had two sons and a daughter. After the War, they were in Amsterdam in the 1920s and in Indonesia in the 1930s. There her marriage ended and Marie spent time in Paris and New York where she had a relationship with the renowned psychoanalyst, Heinz Hartmann, also originally from Vienna

Along with her beauty and her height of 6’1”(growing up in Vienna she was known as the ‘Belle of Vienna’), Paneth was clearly a formidable presence who elicited awe and respect. One of her great friends in England was the writer Elizabeth Jane Howard whom she met in 1941 when learning to type at the famous Pitman’s school. Howard described her as larger than life, unusual and exotic, self-assured and engaging company: “She had a kind of seductive liveliness, an inward amusement at anything we said, enjoying amazing and shocking people with her stories.” (2002, 114).

There is a description of her in the April 1939 issue of The New Yorker focussed on her height. Describing her as ‘the tallest woman painter in the world’ the magazine checked to see if she was actually taller than another painter:

Ms Paneth is 6’1”, a clear inch and a half taller. She’s currently living, and painting, in a roomy studio in Carnegie Hall, and is not overly self-conscious about her height. When she lived in Paris, small boys would stare at her wonderingly and cry out, ‘Madame la Marquise!’ evidently believing that stature and nobility were inseparable, but Americans, used to anything, never do more than ask how the weather is up there. ...Ms Paneth, who has a brother a husband and a son taller than she, is an amiable, dark haired lady with an inventive mind. She’s been here for five months, and her studio is filled with innumerable canvases, pots of ivy and a Chianti tree—her own somewhat surrealistic idea. It consists of four empty Chianti bottles tied on a lamp with lilacs sprouting from the bottles. Takes the place of a lampshade. She is apt to concoct something like this when she’s in a stormy mood.

Marie Paneth seems, in fact, to have stood tall in many senses of the word and is one of the unsung heroes who worked with Holocaust survivors and deprived children.

Paneth was in her mid-40s during WWII when, through her friendship with the Freud family, she became involved in the London East End shelters after visiting them with other volunteers from the Anna Freud Hampstead Nursery. Her approach with the children diverged from Cizek’s in that, while his motto was ‘not to teach, in order to reveal the child’s innate capacity to create ‘primitive’ art,’ her strict rule was: ‘rigorously stick to not interfering at all.’ She used their paintings to assess the effect of war on the child’s psychological makeup and was surprised by the rarity of paintings of destruction and the abundance of drawings of homes. She redefined the healing function of art as that of metaphorically rebuilding a damaged self:

If a child draws a house, be it ever so young and the drawing ever so primitive, the child has made the house and it is filled with the same pride as any grown-up man feels who has just finished building a house…It is the material which, when it fills the soul of the growing individual, will leave less and less room for aggression, depression and bad luck. (1942)

Paneth’s work in Branch Street led to the development of the adventure playground as a place for re-enacting a second childhood – to redeem the damage of the ‘first’. Following Anna Freud’s theory of parental love as an essential component of the socialising process, Paneth explained:

Normally a child gets its first orders from a parent whom it loves. For the sake of this love it starts obeying and, in return for its good behaviour, receives praise and further proofs of love. Then gradually it becomes ready for more and more sacrifice, self-denial, harder work….I was quite sure that our Branch Street children had missed that experience, and the only way by which one could hope to get results which might counterbalance their unlucky start was to give them, now, in some form or other, what they must have missed earlier. (1944, 46-7)

She ends her book saying:

We should also remember that the horde which Hitler employed to carry out his first acts of aggression—murdering and torturing peaceful citizens—was recruited mainly from desperate Branch Street youths, and that to help the individual means helping Democracy as well. (1944, 120)

Her papers, some 600 items, which are held in the Marie Paneth section of the Sigmund Freud Collection in the Library of Congress, include a novel, short stories and an autobiography called Fälschung (Fake), written in both English and German which covers her life until she returned from Indonesia. One can only wonder at this title, ‘Fake’. She herself relentlessly fought to stay true to her psychoanalytically-informed principles. ‘Fake’ has an emphatic anger to it not evident in the gentle, questioning, reflective and humorous narrator of Branch Street.

Her three children all lived in England and her oldest son, Matthias, became a renowned surgeon in London and her daughter married an architect. In 1955 her youngest son, Tony, also a doctor, committed suicide. This would have been an impossible blow and for a while she moved back to New York where she was known as one of the earliest exponents of art therapy, working with psychiatrists and facilitating drawing by their patients.

In the 1960’s she bought a farm near Grasse in the hills north of Cannes where she retired to focus on her own painting, continuing to exhibit her work into her eighties.

She died on November 30, 1986 in the Hazlewell nursing home in Putney. She was ninety-one.

(Text from 2020)

Author: Mary Adams

Links

Library of Congress archive: https://www.loc.gov/item/mm82058735/

First time publication of Marie Paneth's poetic memoir Rock the Cradle, recently discovered in the Library of Congress: https://inews.co.uk/news/long-reads/the-windermere-children-marie-paneth-diary-rock-the-cradle-845857

'Lost Girls' Artwork from the Holocaust, January 15, 2020 by Mark Hartsell: https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2020/01/lost-girls-artwork-from-the-holocaust/

Museum of Modern Art https://documentcloud.adobe.com/link/review?uri=urn:aaid:scds:US:47e6c5f7-ea2b-4ee3-a8e3-c4e5dd2cb614#pageNum=1

Children who came to Windermere: https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2020/jan/05/windermere-children-arek-hersh-survivor-bbc-drama

M.K.Smith https://infed.org/mobi/marie-paneth-branch-street-the-windemere-children-art-and-pedagogy/

Anna Freud account: https://www.thetcj.org/child-care-history-policy/an-experiment-in-group-upbringing-by-anna-freud-and-sophie-dann

The Windermere Children: https://www.historyextra.com/period/second-world-war/orphans-holocaust-children-stories-survivors-lake-district-uk/

Literature & Sources

Avery, T. (2020). The Windemere Project, talking in The Windermere Children. In their own words. (Producer Francis Welch), BBC 4. [https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000dt7g. Retrieved February 12, 2020]

Block, S. (Writer). (2020). The Windemere Children (Director Michael Samuels). First shown: January 27, 2020. IMDb details: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt10370380/

Clifford, R. (2020) https://www.historyextra.com/period/second-world-war/orphans-holocaust-children-stories-survivors-lake-district-uk/

Freud, A. (1937). The ego and the mechanisms of defence. London: Hogarth Press.

Freud, A. in collaboration with Dann, S. (1951). An experiment in group upbringing, The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 6:127-168. Reproduced in 1968 in The writings of Anna Freud. Volume IV Indications for Child Analysis and other papers 1945-1956. (New York: International Universities Press Inc.). The writings of Anna Freud can be borrowed from the Internet Library

[https://archive.org/details/writingsofannafr0004freu/page/162/mode/2up]

Geni.com. Genealogy [https://www.geni.com/people/Marie-Paneth/6000000007470155807. Retrieved January 12, 2020].

Gutteridge, M. V. (undated). The classes of Franz Cizek, The Free Library. [https://www.thefreelibrary.com/The+classes+of+Franz+Cizek.-a08934232. Retrieved: January 17, 2020]

Hartnell, M. (2020). ‘Lost Girls’ Artwork from the Holocaust, Library of Congress Blog January 15, 2020. [https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2020/01/lost-girls-artwork-from-the-holocaust/. Retrieved: January 18, 2020].

Hogan, S. (2001). Healing Arts: The history of art therapy. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Howard, E. J. (2002). Slipstream. A memoir. London: Macmillan

Jeffs, T. (2003). Classic texts revisited – Branch Street by Marie Paneth. Youth & Policy 81. [https://www.youthandpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/y-and-p-81.pdf. Retrieved January 14, 2020].

Johnson, J.M (2012). The Memory Factory; The Forgotten Women Artists of Vienna 1900. Purdue University.

Kelly D. (2004). Uncovering the history of children’s drawing and art.

Koslovsky, R.: The Junk Playground. Creative destruction as an antidote to delinquency. Paper presented at the Threat and Youth Conference, Teachers College, April 1, 2006. [http://threatnyouth.pbworks.com/f/Junk%20Playgrounds-Roy%20Kozlovsky.pdf. Retrieved: January 16, 2020]

Koslovsky, R. (2007). Adventure Playgrounds and Post-war Reconstruction in Gutman, M./de Coning-Smith, N. (Hg.): Designing modern childhoods: History, Space and Material Culture of Children: An International Reader. Rutgers.

Koslovsky, R. (2013). The Architectures of Childhood; Children, Modern Architecture and Reconstruction in Postwar England. Poutledge.

Korotin, I and Stupnicki, N. (2018). Biografien bedeutender österreichischer Wissenschafterinnen»Die Neugier treibt mich, Fragen zu stellen. Wien – Köln – Weimar: Böhlau Verlag. [https://austria-forum.org/web-books/biografienosterreich00de2018isds/000667. Retrieved January 12, 2020].

McAleer, M. (2010). Marie Paneth Papers. A Finding Aid to the Papers in the Sigmund Freud Collection in the Library of Congress. Washington DC.

Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) (1948a). Art Work by Children of Other Countries. Exhibition Record [https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3236?. Retrieved December 19, 2019].

Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) (1948b). Concentration camp children’s art from Europe to be compared with the work of D.P. children, in America. Press Release. New York: MOMA. [https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_press-release_325598.pdf. Retrieved: January 14, 2020].

The National Archives; Kew, London, England; HO 396 WW2 Internees (Aliens) Index Cards 1939-1947; Reference Number: HO 396/67 [Retrieved May 28, 2020]. [NB there are two cards with the same reference – one for the appeal, another detailing the exemption].

Paneth, M. (1944). Branch Street. A sociological study. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Paneth, M. (1946). Rebuild those lives, Free World, April 1946. [https://www.unz.com/print/FreeWorld-1946apr-00053/. Retrieved January 15, 2020]

Smith, M. K. (1999-2019) ‘Social pedagogy’ in The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education, [https://infed.org/mobi/social-pedagogy-the-development-of-theory-and-practice/. Retrieved: January 16, 2020].

Smith, Mark K. (2006). George Goetschius, community development and detached youth work, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/george-goetschius-community-development-and-detached-youth-work/. Retrieved: December 22, 2019].

Smith, M. K. (2007a). M. Joan Tash, youth work, and the development of professional supervision, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/m-joan-tash-youth-work-and-the-development-of-professional-supervision/. Retrieved: December 22, 2019].

Smith, M. K. (2007b) ‘Classic studies in informal education – Working with unattached youth’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/classic-studies-working-with-unattached-youth/. Retrieved: December 22, 2019].

Smith, M. K. (1996, 2020). Marie Paneth – Branch Street, The Windemere Children and art therapy and pedagogy. The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/marie-paneth-branch-street-the-windemere-children-art-and-pedagogy/].

Viola, W. (1936). Child Art and Franz Cizek. Vienna: Austrian Junior Red Cross | New York: Reynal and Hitchcock. [https://another-roadmap.net/articles/0002/8598/viola-cizek-textteil.pdf. Retrieved January 16, 2020]

Weininger, S. S. (2020). Society of Independent Artists [SIA], Oxford Art Online/Grove Art Online. [https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T079485. Retrieved January 15, 2020].

Winnicott, D. W. (1959). Obituary: Oscar Friedman in L. Caldwell and H. T. Robinson (eds.). The Collected Works of D. W. Winnicott: Volume 5, 1955-1959. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.