(Marianne von Werefkin; Марианна Владимировна Верёвкина; Marianna Wladimirowna Werjowkina; Marianna Vladimirovna Verëvkina [wissenschaftliche Transliteration])

born 11 September 1860 in Tula, Russia

died 6 February 1938 in Ascona, Switzerland

Russian painter, art theorist and patroness/sponsor

160th Birthday September 11, 2020

Biography • Literature & Sources

Biography

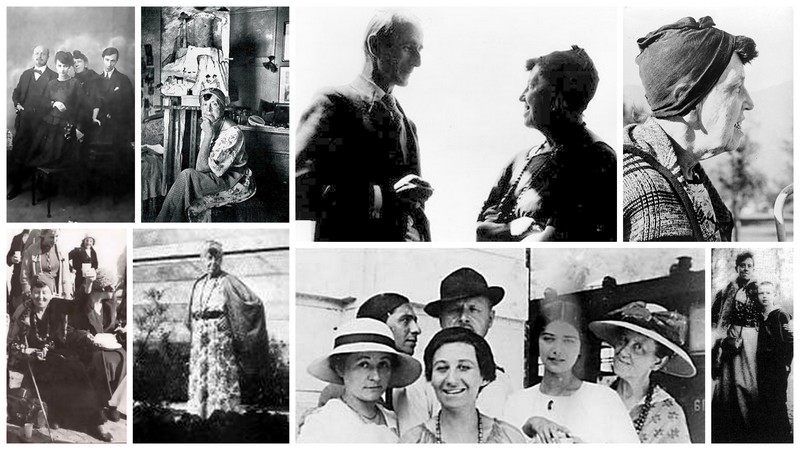

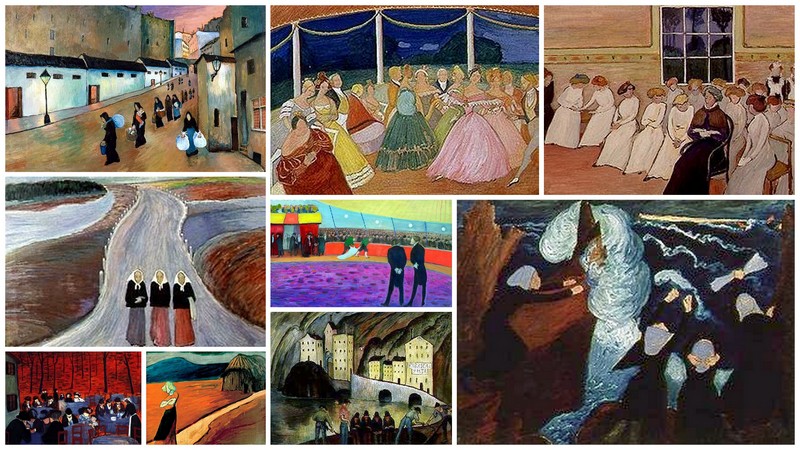

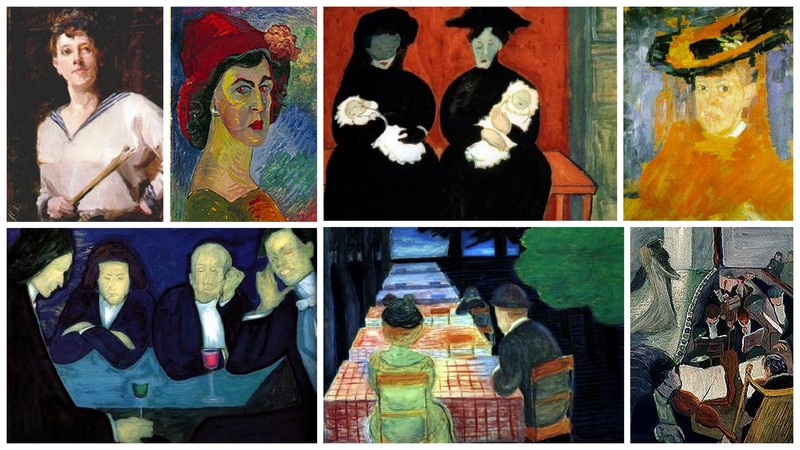

The bold self-portrait of Marianne Werefkin at 50 is a favorite cover choice for books about women painters, with its red, passionately glowing eyes, its proud gaze, and its “unnatural colors and whirling brushstrokes.” It took a long time for women artists to win admission to their profession, and the revolutionary Werefkin embodies and depicts this breakthrough more triumphantly and convincingly that almost any other. Her self-portrait reflects “the personal dramatic self-image of Werefkin” (Mangold) and thus appears quite the opposite of what was expected of a lady. Werefkin was ahead of her time not only as an artist and a theoretician of art, but also as a woman – but only after she had first carried the “feminine” ideal of self-sacrifice and renunciation to an extreme hard for us to understand today, and then overcome it.

Werefkin grew up in a cultivated and wealthy aristocratic family; her mother was a painter, her father a general – for his meritorious service during the Crimean War, Czar Alexander II granted him the estate Blagodat in Lithuania, the family’s beloved summer retreat. There Werefkin had her own studio house. After her parents had discovered their daughter’s extraordinary talent in 1874, they immediately saw to it that she received professional drawing instruction. In 1880 the most distinguished realist painter of Russia, Ilya Repin, became her private teacher.

In 1888 Werefkin had a hunting accident and shot herself in the right hand, her painting hand. She would not have been Werefkin, however, if she had allowed a missing middle finger to keep her from pursuing her goals. A far greater obstacle would be her 27-year-long relationship to Jawlensky. She met the impoverished officer, four years her junior, in 1892; he had just begun painting, while she had already exhibited and was recognized as the “Russian Rembrandt.”

Werefkin knew that Jawlensky was a skirt-chaser: “Love is a dangerous matter, especially in Jawlensky’s hands.” She declined to marry him not least because of the generous pension from the Czar which she would have lost as a married woman. But she had decided that she wanted to promote and encourage him as an artist in every way possible. He should achieve in her stead and realize artistically everything from which, after all, a “weak woman” was barred anyway. “Three years passed in indefatigable care of his mind and heart. Everything, everything that he received from me I pretended to take – everything that I poured into him I pretended to receive … so that he wouldn’t feel jealous as an artist, I hid my art from him.” (Werefkin, in Fäthke 1980:17).

Jawlensky thanked her by sexually abusing nine-year-old Helene Nesnakomoff, the helper of Werefkin’s maid, with whom he was also already involved. In 1902 Helene gave birth to a son. In the same year Werefkin began her journal “Lettres à un Inconnu.” With his penchant for the kitchen help Jawlensky had failed as a partner to such a degree that she had to invent an “Unknown” as her vis-à-vis. Twenty years later, when Werefkin was impoverished, it suited Jawlensky to distance himself completely from her, and he deigned to marry the mother of his son.

In 1896, after the death of her father, Werefkin hat moved with her entourage to Schwabing in Munich, where she was soon hosting a famous salon where the art world gathered to discuss the latest developments. Werefkin was the primary theorist and stimulator of new ideas. By 1906 she had overcome her decade-long Jawlensky-crisis and returned to painting herself, and in the years up to the beginning of World War I she created groundbreaking works (such as her famous self-portrait) that, far ahead of their time, anticipated the trends of the future.

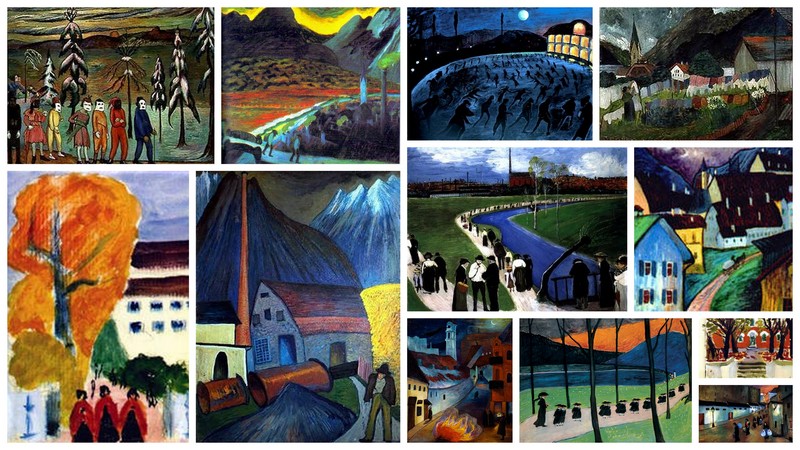

The village of Murnau in the Bavarian Alps became the birthplace of abstract painting in the summer of 1908, when the artist couple Gabriele Münter and Wassily Kandinsky joined Werefkin and Jawlensky to live, paint, and debate there together. Kandinsky, with his essay “Über das Geistige in der Kunst” (1911/12; “Concerning the Spiritual in Art”), has usually been considered the leading thinker of the group. But it has since been shown by Werefkin’s biographer Fäthke that he took many of his ideas from Werefkin, without, however, mentioning their source.

In 1909 the Neue Künstlervereinigung München (NKVM; Munich New Artists’ Association) was founded. After an ugly intrigue, initiated by Kandinsky, Marc and Macke, the “Blaue Reiter” (Blue Rider group) split off from the NKVM. Werefkin also left the NKVM in 1912 and became “des blauen Reiterreiterin” (the Blue Rider’s woman rider), as her friend, the poet Else Lasker-Schüler called her.

With the outbreak of the first World War Werefkin moved with Jawlensky to neutral Switzerland. She lost her Czarist pension through the Russian revolution. Completely impoverished, but creatively unbroken, and supported by good friends and admirers of her work, she spent the last quarter of her long life in Ascona. She donated many of her paintings to the city, which today possesses the largest collection of Werefkin’s works. They can be admired in the Museo comunale di Ascona, where the Fondazione Marianne Werefkin is based.

trans. Joey Horsley

For additional information please consult the German version.

Author: Luise F. Pusch

Literature & Sources

Behling, Katja & Anke Manigold. 2009. Die Malweiber: Unerschrockene Künstlerinnen um 1900. München. Sandmann.

Behr, Shulamith. 1988. Women Expressionists. New York. Rizzoli.

Berger, Renate. 1982. Malerinnen auf dem Weg ins 20. Jahrhundert: Kunstgeschichte als Sozialgeschichte. Köln. Dumont TB 121.

Brögmann, Nicole. 1996. Marianne von Werefkin: Œuvres peintes, 1907-1936. Texte von Madeleine Strobel Neumann u.a. Gingins, Schweiz. Fondation Neumann en coopération avec le Museo communale d'arte moderna, Ascona.

Fäthke, Bernd. 1988. Marianne Werefkin: Leben und Werk; 1860-1938. München. Prestel.

Fäthke, Bernd. 2001. Marianne Werefkin. München. Hirmer.

Fäthke, Bernd. 2004. Jawlensky und seine Weggefährten in neuem Licht. München. Hirmer.

Gagel, Hanna. 2005. So viel Energie: Künstlerinnen in der dritten Lebensphase. Berlin. AvivA.

Krause, Barbara. 2000. Der blaue Vogel auf meiner Hand: Marianne Werefkin und Alexej Jawlensky. Romanbiographie. 2. neuausgestatt. Aufl. Freiburg. HerderSpektrum.

Marianne Werefkin: Gemälde und Skizzen. 1980. Ausstellungskatalog. Wiesbaden. Museum Wiesbaden.

Möller, Hildegard. 2007. Malerinnen und Musen des “Blauen Reiters”. München; Zürich. Piper.

Salmen, Brigitte, Bernd Fäthke & Annegret Hoberg. 2008. 1908-2008, vor 100 Jahren, Kandinsky, Münter, Jawlensky, Werefkin in Murnau. Eine Sonderausstellung im Schloßmuseum Murnau, 11. Juli bis 9. November 2008. Murnau. Schloßmuseum.

Weidle, Barbara. Hg. 1999. Marianne Werefkin: Die Farbe beisst mich ans Herz. Vorwort Margarethe Jochimsen. Illustr. Fondazione M. Werefkin, Ascona. Bonn. August Macke Haus.

Werefkin, Marianne. 1999. Lettres à un inconnu. Présentation par Gabrielle Dufour-Kowalska. Paris. Klincksieck.

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.