Biographies Margarete von Tirol

(Margarethe Maultasch, Margarete Maultasch, Margarethe von Tyrol; Margaretha Maultasch)

Margarete of Tyrol

called Margarete Maultasch

Born 1318 in Tyrol

Died 3 October 1369 in Vienna

Ruler of Tyrol

Biography

Margarete, called »Maultasch« (“Mouthpocket”), was the daughter of Adelheid of Braunschweig (Brunswick) and the Tyrolean count Heinrich, also Duke of Kärnten (Carinthia). She was twelve when she was married to the son of the king of Bohemia, three years her junior. After the death of her father in 1335 young Margarete took charge of political affairs in the entire country, which was threatened at the time by the most powerful European dynasties. She lost Kärnten, but successfully defended Tyrol in alliance with its nobility. In 1341 she denied her husband entry to Schloss Tirol (the Castle of Tyrol), thereby forcing him to flee. She accused him of being violent and infertile. Emperor Ludwig (Louis) of Bavaria, who had been cultivating expansionist aims for some time, urged her to marry his son Ludwig of Brandenburg. He declared Margarete’s first marriage to be null and void and went forward with the match between her and his son despite the resistance of the pope. As a result of this new, ecclesiastically unsanctioned marriage, the Church imposed a ban on Margarete and her country which lasted for 17 years.

Times were hard for Tyrol to begin with: several times between 1338 and 1341 locusts devastated the fertile lands; in 1344 a violent earthquake rocked the area between Bolzano and Merano, the same region which had been flooded a few years earlier and would be afflicted by plague four years later. In 1347 Margarete was able to stave off the renewed attacks of Emperor Karl (Charles) IV, the brother of her first husband; he had hoped to take advantage of Ludwig’s absence to conquer Tyrol. Margarete put up heroic resistance and defended her land effectively until her husband’s return. Ludwig died suddenly in 1361 during a visit to Munich. Two years later Margarete’s only surviving son, Meinhard III, also died. On 29 September 1363 she gave over her familial land of Tyrol to the Habsburgs and withdrew to Vienna. Isolated and lonely, she died there in 1369 at age 51. ***

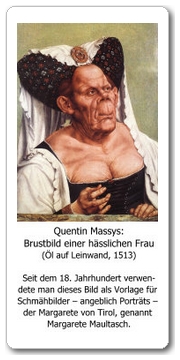

Many legends have grown up around the figure of Margarete Maultasch. In the collective imagination and imagery she was made into the epitome of an ugly, violent and sex-hungry virago. She was almost certainly never in Kärnten – and yet the legends tell in detail of her military exploits there, of destroyed forts and castles, mercilessly devastated regions, incredible outrages against women, children and old people. In the Steiermark (Styria) and the region of Salzburg she is described as an Amazon in armor who rode on a black horse with illuminated breath visible at night. She fed on raw meat, grabbed and clung to men and sucked out or bathed in their blood. Elsewhere the following episode is recounted: Margarete, widowed for the second time, promises to give her country to the most sexually potent man. Many attempt the challenge, but none succeeds in satisfying Margarete. A number of nobles refuse to participate, because the sovereign is allegedly so ugly and misshapen. Abundantly grotesque mystifications concerning Margarete’s death are also part of the tradition: after having had enough of lascivious sex with men she gives herself to a mule for whom she orders a large bed built. She ends miserably, pressed to death by the animal.

Such distorted tales are nothing new in the history of women. Since antiquity powerful women have been accused of having an overwhelming, ungovernable sexual life; the association of female power and wild, excessive sexuality runs through history as a literary topos. And in the case of Margarete as well, historiography blends autonomous power, ugliness and sexual immorality.

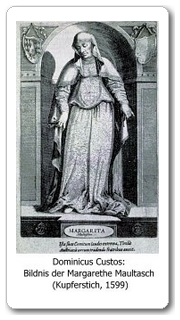

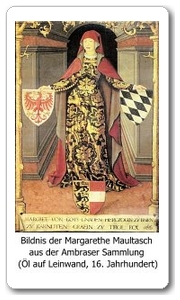

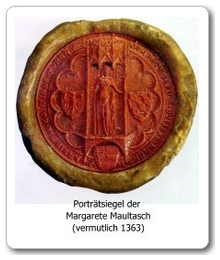

The legends assume that the sobriquet “Maultasch” derives from her large, distorted mouth and loose-hanging jaw. Reality tells a different story: the only portrait that stems from her time is a seal-image made in connection with the document transferring Tyrol to the Habsburgs; it shows a comely, lissome, elegant female image, which is, however, not clearly recognizable. And in the written documents of her time Margarete’s beauty is praised. Johann von Winterthur (d. 1348) describes her as pulchra nimis (very beautiful); Heinrich von Herford (d. 1370) as tam pulchra tam generosa (as beautiful as she is generous).

Even today the figure of Margarete Maultasch eludes our grasp, primarily because of the layers of interwoven history and myth that have accumulated over the years. Margarete was made into a “monster” over time. And yet she remains simultaneously the symbol of distinctive differentness and many-sidedness which cannot be reduced to a single formula.

“Love’s long absence is the hook to catch my heart” (»Liebes langer Mangel ist maines Herzen Angel«?) is engraved in the silver bridal chalice that Margarete received as a wedding gift from Ludwig of Brandenburg.

trans. Joey Horsley

For additional information please consult the German version.

Author: Barbara Ricci und Donatella Trevisan

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.