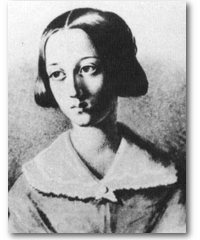

Biographies Malvida von Meysenbug

(Malwida Rivalier [birth name]; Malwida Freiin von Meysenbug)

Born October 28, 1816 in Kassel

Died April 26, 1903 in Rome

German writer and intellectual

Biography • Quotes • Weblinks • Literature & Sources

Biography

The popular movements for greater freedom of the Revolution of 1848 as well as their failure were defining events in the extraordinary life of Malvida von Meysenbug. Her father was a high-ranking government official in the Electorate of Hesse-Kassel. Her mother, Ernestine Hansel, was an exceptionally well-educated woman who taught her children herself. Her daughter Malvida was born in 1816 at Schöne Aussicht No. 7 in Kassel; she was the second youngest of ten children. In 1830, when the unrest of the July Revolution in France spread to Kassel, the Prince-elector was ultimately forced to leave Kassel and turned over the government to his son. Malvida’s father followed him into exile, and his family had to leave Kassel as well. Following a long series of temporary stays, the mother finally settled with her youngest children at her daughter’s home in Detmold, a city in present-day North-Rhine Westphalia.

Malvida von Meysenbug was introduced to the liberal democratic ideals of the Vormärz period that preceded the 1848 March Revolution through her relationship with the theologian Theodor Althaus, a democrat who had renounced the church and become an adherent of the Free Thought movement. He was six years younger than Meysenbug and still at the beginning of his professional career. Although Meysenbug did not wish to impede his advancement through a bond of marriage, she was deeply disappointed when Althaus turned his affection to another woman. As Meysenbug’s commitment to democratic ideas grew, so too did the chasm between her and her family until it was finally irreconcilable.

During a visit to Frankfurt in March 1848, Meysenbug enthusiastically followed – from a hiding place in the gallery of the Church of St. Paul (Paulskirche) – the debates leading up to the first German national parliament. When after her father’s death in 1847 it was revealed that his estate was more meager than expected, Meysenbug took the opportunity to assert her financial independence. She found a new pursuit at the Hochschule für das weibliche Geschlecht, a women’s college in Hamburg run by Johanna and Karl Froebel, and joined the Free Church. In so doing, she renounced the state church and relinquished her right as a noblewoman to be cared for in old age in an endowed monastery.

The Revolution of 1848 had failed; the democrats were persecuted and jailed. The Hamburg women’s college had to close in 1852 due to financial problems and internal disputes, and Theodor Althaus died the same year. Deeply depressed, Meysenbug sought solace from a friend in Berlin. Following a visit from Meysenbug’s brother, who tried to dissuade her from her religious and political ideas, her residence was searched by the police. Meysenbug averted looming deportation from Germany by fleeing to London. She earned her living in exile as a teacher and governess and became friends with the married couple and fellow exiles Johanna and Gottfried Kinkel. She lived with the widowed Russian writer and socialist Alexander Herzen and assumed responsibility for the education of his daughters. Meysenbug left Alexander Herzen because of rivalries with a married couple who were also Russian émigrés, but continued to translate articles for him from Russian.

In 1859, Malvida von Meysenbug left London and, after several stays in Paris, finally settled in Rome, where at Alexander Herzen’s request she resumed the education of his daughter, Olga. Rome was where Meysenbug produced her most important writings, most notably Memoiren einer Idealistin (Memoirs of an Idealist). She maintained contact with prominent artists and philosophers of her day, was an ardent admirer of the music of Richard Wagner, spent several weeks in Bayreuth, and became a motherly friend to Friedrich Nietzsche and Romain Rolland. Malvida von Meysenbug died at age 86 on April 26, 1903 in Rome.

(Text from 2002; transl. Julie Niederhauser, 2021)

Author: Hiltrud Schroeder

Quotes

To be independent is my most fervent wish.

Life itself is the purpose of life. To have lived is our task. However lofty or humble one

understands it to be is up to each individual.(From: Der Lebensabend einer Idealistin [Twilight Years of an Idealist].

Links

“Malwida von Meysenbug”, Blog, available at: malwidameysenbug.blogspot.de/ (accessed 10 February 2021).

“Malwida von Meysenbug-Gesellschaft e.V.”, available at: www.meysenbug.de/ (accessed 10 February 2021).

Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek, “Malwida von Meysenbug”, available at: www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/entity/118582054 (accessed 10 February 2021).

Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, “Meysenbug, Malwida von”, available at: d-nb.info/gnd/118582054 (accessed 10 February 2021).

Freie Universität Berlin, Universitätsbibliothek (2013), “Malwida von Meysenbug”, available at: web.archive.org/web/20131011170626/http://www.ub.fu-berlin.de/service_neu/internetquellen/fachinformation/germanistik/autoren/autorm/meysenbug.html (accessed 10 February 2021).

Geschichtswerkstatt Bayreuth e. V. (2012), “Malwida von Meysenbug”, available at: www.geschichtswerkstatt-bayreuth.de/frauen.htm#Malwida (accessed 10 February 2021).

Häntzschel and Hiltrud, “Meysenbug, Malwida Freiin von”, In: Neue Deutsche Biographie 17 (1994), S. 407-409 [Onlinefassung]; URL: https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/gnd118582054.html#ndbcontent, available at: www.deutsche-biographie.de/gnd118582054.html#ndbcontent (accessed 10 February 2021).

Nerger, K., “Grabstätten weltweit – Schriftsteller 57 – Malvida Freiin von Meysenbug”, available at: www.knerger.de/html/meysenbuschriftsteller_57.html (accessed 10 February 2021).

Projekt Gutenberg, “Malwida von Meysenbug Leben und Werk”, available at: gutenberg.spiegel.de/autor/malwida-von-meysenbug-1064 (accessed 10 February 2021).

Verbundkatalog HAN, “Nachlass Malwida von Meysenbug (1816-1903)”, available at: aleph.unibas.ch/F/?local_base=DSV05&con_lng=GER&func=find-b&find_code=SYS&request=000069859 (accessed 10 February 2021).

Zeno, “Meysenbug, Malwida Freiin von”, available at: www.zeno.org/Literatur/M/Meysenbug,+Malwida+Freiin+von (accessed 10 February 2021).

.

Literature & Sources

Sources

Goodman, K. (1986), Dis/closures: Women's autobiography in Germany between 1790 and 1914, New York University Ottendorfer series, Vol. 24, Lang, New York, Berne etc.

Leisner, B. (1998), Malwida von Meysenbug: »Unabhängig sein ist mein heißester Wunsch«, Econ & List, 26515 Rebellische Frauen, Orig.-Ausg, Econ-und List-Taschenbuch-Verl., München.

Meysenbug, M.v. (1876), Memoiren einer Idealistin und ihr Nachtrag: Der Lebensabend einer Idealistin, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Berlin.

Meysenbug, M.v. (1985), Memoiren einer Idealistin, Insel-Taschenbuch, Vol. 824, 1st ed., Insel-Verl., Frankfurt am Main.

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.