Biographies Karoline von Günderrode

German author

Born 11 February 1780 in Karlsruhe

Died 26 July in Winkel in Rheingau

200th anniversary of death on 26 July 2006

Biography • Quotes • Literature & Sources

Biography

Karoline, the oldest of six siblings, came from a cultivated but impoverished aristocratic family. In 1797 she entered a residence for noblewomen in Frankfurt, an institution in which poor unmarried aristocratic ladies were cared for and could live respectably while still keeping an eye out for a suitable marriage partner. Karoline was described as beautiful, gentle and shy. She and her friend Lisette Mettingh discussed society’s discrimination against women. One way to escape such limitations was education, which Karoline acquired by indefatigable reading. She was soon as knowledgeable as the best-educated of her time. Karoline concerned herself with literature, philosophy, far-eastern and Norse mythology, chemistry, geography, history of religion, physiognomy, Latin and prosody. She also wrote dramas, poetry, and above all letters—the letter established itself during the Romantic period as a literary genre in its own right. Letters were a demonstration of intellectual cultivation and emotional sensitivity and, since they were usually read aloud, were always written with a semi-public audience in mind. Because of an eye ailment Karoline suffered her life long from severe headaches and wrote on green paper to spare her eyes.

Karoline, the oldest of six siblings, came from a cultivated but impoverished aristocratic family. In 1797 she entered a residence for noblewomen in Frankfurt, an institution in which poor unmarried aristocratic ladies were cared for and could live respectably while still keeping an eye out for a suitable marriage partner. Karoline was described as beautiful, gentle and shy. She and her friend Lisette Mettingh discussed society’s discrimination against women. One way to escape such limitations was education, which Karoline acquired by indefatigable reading. She was soon as knowledgeable as the best-educated of her time. Karoline concerned herself with literature, philosophy, far-eastern and Norse mythology, chemistry, geography, history of religion, physiognomy, Latin and prosody. She also wrote dramas, poetry, and above all letters—the letter established itself during the Romantic period as a literary genre in its own right. Letters were a demonstration of intellectual cultivation and emotional sensitivity and, since they were usually read aloud, were always written with a semi-public audience in mind. Because of an eye ailment Karoline suffered her life long from severe headaches and wrote on green paper to spare her eyes.

Karoline was a friend of Bettina, Gunda and Clemens von Brentano. Bettina and Karoline enjoyed role-playiing, and Karoline always took on the male role and was jokingly named “Günter” by Bettina. Karoline was unable to come to terms with the prescribed feminine role and, ahead of her time, observed: “Masculinity and femininity, as they are usually understood, are obstacles to humanity.” She suffered severely under the limitations of these roles. In a letter to Gunda von Brentano she writes: “I’ve often had the unfeminine desire to throw myself into the wild chaos of battle and die. Why didn’t I turn out to be a man! I have no feeling for feminine virtues, for a woman’s happiness. Only that which is wild, great, shining appeals to me. There is an unfortunate but unalterable imbalance in my soul; and it will and must remain so, since I am a woman and have desires like a man without a man’s strength. That’s why I’m so vacillating and so out of harmony with myself….” Karoline suffered from a nervously induced melancholy and had an unpredictable temperament that alienated some. At the same time she enjoyed going to parties and was interested in social dancing, housekeeping, needle-work and making music. At one social evening she met Friedrich Karl von Savigny, at the time still a law student, and fell passionately in love. They grew close enough for her to hope for a wedding, but Savigny, put off by Günderrode’s high level of education, preferred to marry the less intellectual Gunda von Brentano.

Karoline was a friend of Bettina, Gunda and Clemens von Brentano. Bettina and Karoline enjoyed role-playiing, and Karoline always took on the male role and was jokingly named “Günter” by Bettina. Karoline was unable to come to terms with the prescribed feminine role and, ahead of her time, observed: “Masculinity and femininity, as they are usually understood, are obstacles to humanity.” She suffered severely under the limitations of these roles. In a letter to Gunda von Brentano she writes: “I’ve often had the unfeminine desire to throw myself into the wild chaos of battle and die. Why didn’t I turn out to be a man! I have no feeling for feminine virtues, for a woman’s happiness. Only that which is wild, great, shining appeals to me. There is an unfortunate but unalterable imbalance in my soul; and it will and must remain so, since I am a woman and have desires like a man without a man’s strength. That’s why I’m so vacillating and so out of harmony with myself….” Karoline suffered from a nervously induced melancholy and had an unpredictable temperament that alienated some. At the same time she enjoyed going to parties and was interested in social dancing, housekeeping, needle-work and making music. At one social evening she met Friedrich Karl von Savigny, at the time still a law student, and fell passionately in love. They grew close enough for her to hope for a wedding, but Savigny, put off by Günderrode’s high level of education, preferred to marry the less intellectual Gunda von Brentano.

After her unrequited love for Savigny Karoline devoted herself primarily to art, in order to perfect her personality, as she said. She wanted to unite life and writing in art. Here she oriented herself especially on Schelling, who became her favorite thinker, along with Fichte, Schlegel and Novalis. She wrote dramas, such as Hildegund und Nikator and Mora, in which strong, heroic women usually played a central role. In her works she criticized the ideals of bourgeois society and its traditional gender roles.

She became increasingly lonely as her sister and two of her female friends married. Writing now became more and more a means of self-assertion. Under the male pseudonym Tian she published Gedichte und Phantasien (Poems and Fantasies), a work consisting of lyrical-epic poems, dramatic fragments and prose pieces. Her poetic works are stamped by the philosophy of the Romantic movement and transmit notions of death as rebirth which she sought in myths and religions of Asia and ancient Egypt. She wanted to be able to think and simultaneously experience the unity of ego and world. The high point of her poetic creativity is Die Idee der Erde (The Idea of the Earth). Here she develops the principle of “the splendid,” by which she understands the process of becoming one with nature.

In August 1804 she met the Heidelberg philologist and archeologist Friedrich Creuzer, who was married to a woman 13 years his senior. A great love developed between them; they were compatible both personally and in scholarly and literary terms. They shared common interests and encouraged each other’s work. They even had plans for a joint project—ideal conditions for a life together. Creuzer’s wife had even agreed to a divorce, but Creuzer suffered depression and anxiety about a public scandal because of his secret love for Günderrode. He sought advice from two colleague friends and put off the divorce. His friends adviced him against marriage to Günderrode: she would never be a respectable housewife, and moreover, her devotion to the study of Schelling’s ideas was cause for serious concern. Now Creuzer demanded of her that she write his friends a letter in which she promised to lead a quiet married life and give up reading Schelling. Karoline resisted these unreasonable expectations and developed a plan to flee with Creuzer to Alexandria or else to travel in male disguise to Russia. She also claimed she wanted to die with Creuzer. Under all this tension Creuzer became ill and asked his friend Daub to write a farewell letter to Günderrode. Karoline found herself at the time in Winkel im Rheingau. She set off on a walk to the Rhine and killed herself with a dagger.

In August 1804 she met the Heidelberg philologist and archeologist Friedrich Creuzer, who was married to a woman 13 years his senior. A great love developed between them; they were compatible both personally and in scholarly and literary terms. They shared common interests and encouraged each other’s work. They even had plans for a joint project—ideal conditions for a life together. Creuzer’s wife had even agreed to a divorce, but Creuzer suffered depression and anxiety about a public scandal because of his secret love for Günderrode. He sought advice from two colleague friends and put off the divorce. His friends adviced him against marriage to Günderrode: she would never be a respectable housewife, and moreover, her devotion to the study of Schelling’s ideas was cause for serious concern. Now Creuzer demanded of her that she write his friends a letter in which she promised to lead a quiet married life and give up reading Schelling. Karoline resisted these unreasonable expectations and developed a plan to flee with Creuzer to Alexandria or else to travel in male disguise to Russia. She also claimed she wanted to die with Creuzer. Under all this tension Creuzer became ill and asked his friend Daub to write a farewell letter to Günderrode. Karoline found herself at the time in Winkel im Rheingau. She set off on a walk to the Rhine and killed herself with a dagger.

(translated by Joey Horsley)

Author: Sibylle Duda

Quotes

I can’t understand the change in your feelings. How often have you told me that my love brightens, enlivens your whole existence, and now you find our relationship damaging. How much would you have given once to win this “damage” for yourself! But that’s the way you [men] are, what you’ve conquered always seems to be lacking….You seem to me like a boatsman to whom I’ve entrusted my whole life, but now the storms are raging, the waves rise up. The winds bring me scattered sounds; I listen and hear how the boatsman takes counsel with his friends whether he shouldn’t throw me overboard or put me ashore on the barren coast? (Karoline von Günderrode to Friedrich Creuzer)

Literature & Sources

Karoline von Günderrode in the German National Library

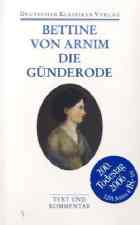

Arnim, Bettina von. 1992 [1840]. Die Günderode. Mit einem Essay von Christa Wolf. Frankfurt/M. Insel TB.

Arnim, Bettina von. 1992 [1840]. Die Günderode. Mit einem Essay von Christa Wolf. Frankfurt/M. Insel TB.

Arnim, Bettina von. 2006 [1840]. Die Günderrode. [Text und Kommentar]. Hg. Walter Schmitz. Frankfurt/M. Deutscher Klassiker-Verlag im Taschenbuch.

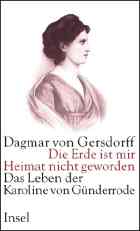

Gersdorff, Dagmar von. 2006. Die Erde ist mir Heimat nicht geworden: Das Leben der Karoline von Günderrode. Frankfurt/M. Insel.

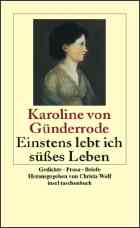

Günderrode, Karoline von. 1997 [1979]. Der Schatten eines Traumes: Gedichte, Prosa, Briefe, Zeugnisse von Zeitgenossen. Hg. und mit einem Essay von Christa Wolf. München. dtv.

Günderrode, Karoline von. 1998. Gedichte, Prosa, Briefe. Hg. von Hannelore Schlaffer. Stuttgart. Reclam.

Hille, Markus. 1999. Karoline von Günderrode. Reinbek b. Hamburg. rororo monographie.

Wolf, Christa. 2002 [1979]. Kein Ort. Nirgends. München. Luchterhand.

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.