(Käthe Ida Kollwitz geb. Schmidt)

born 8 July 1867 in Königsberg

died 22 April 1945 in Moritzburg near Dresden

German graphic artist and sculptor

150th birthday on July 8, 2017

Biography • Literature & Sources

Biography

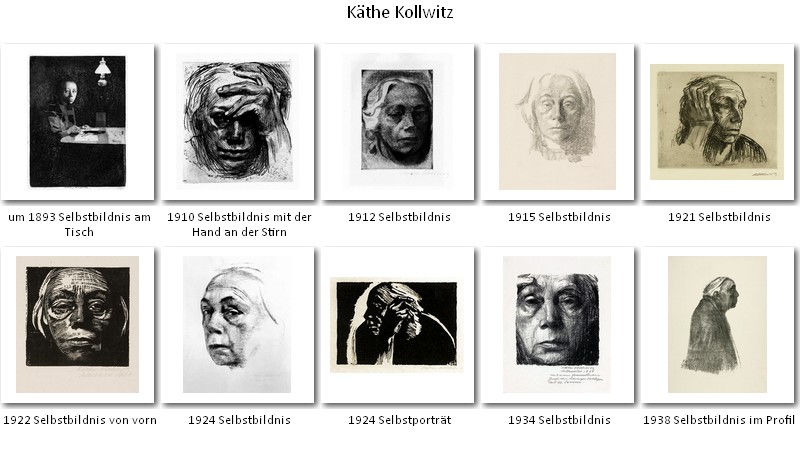

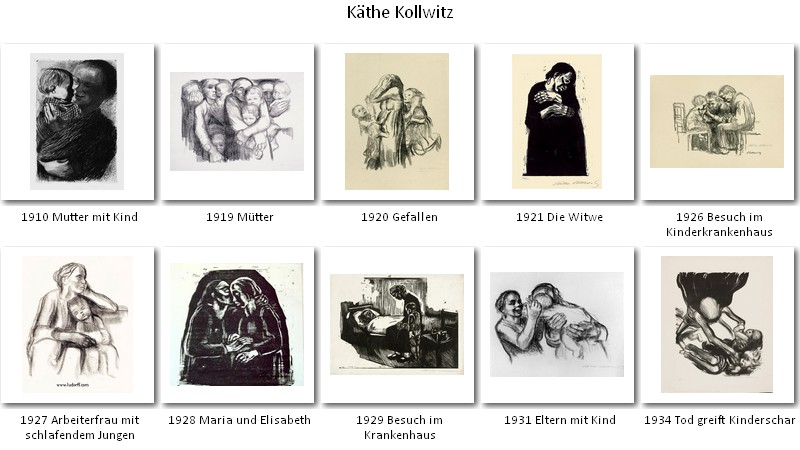

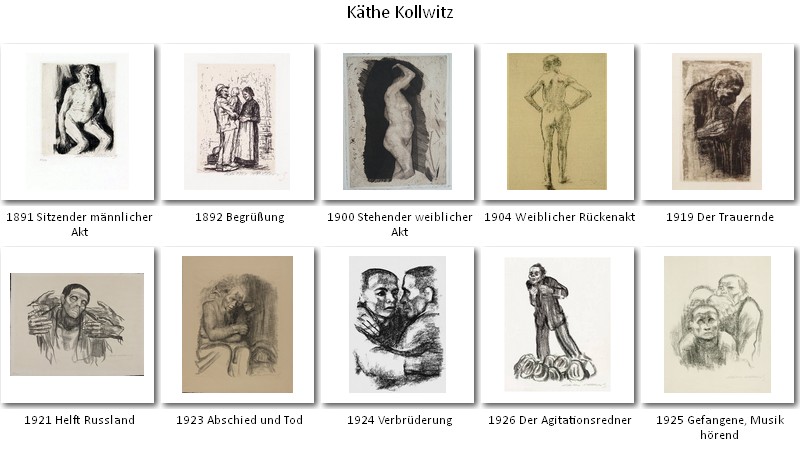

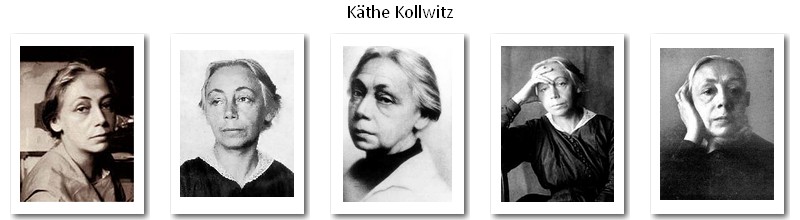

Käthe Kollwitz, in her lifetime – and after – Germany’s best-known female artist, is also famous as a public figure who spoke out in her art and her words for the values she believed in: social democracy, international pacifism, concern for the poor and downtrodden. Her most important graphic and sculptural works reflect aspects of life that she herself experienced deeply; the protective or grieving mother is a recurrent theme. As a female artist Kollwitz was in many respects a pioneer, overcoming traditional barriers to become the first woman admitted to the Prussian Academy of Arts (1919) and the first to receive the highest honor of the Weimar Republic, the “Orden Pour le Mérite” (1929). Her life spans the years from the Prussian monarchy and so-called Second Reich through the devastating First World War, tumultuous Weimar Republic, repressive Third Reich and Second World War. Through it all Kollwitz was a keen observer and conscientious participant, as her deeply thoughtful diaries (1908-1943) and other writings, as well as her art, reveal. The diaries further testify to Kollwitz’ lifelong interrogation of her own positions and feelings as she wrestled with personal yet universal themes such as death or an artist’s relationship to her art. The multitude of self-portraits she created over her lifetime, comparable in quantity to those of Rembrandt, underscores the probing, self-reflective nature of this artist. Her letters and diaries also reveal struggles with depression and phases of creative discouragement, as well as a strong capacity for joy and sensuality.

Käthe was born and grew up in Königsberg, the city where Immanuel Kant had preached the ideas of Enlightenment, and where her grandfather, theologian and preacher Julius Rupp, was removed from his post in the state church for his insistence on absolute freedom of conscience. Rupp subsequently founded the Freie Gemeinde (Free Congregation), a religious community based on Biblical ideas of a classless society, one which granted women an unusual degree of equality. Käthe’s mother was Rupp’s oldest daughter Katharina. Like her grandfather, Käthe’s father Carl Schmidt was a “republican,” a supporter of the 1848 revolution, as well as a member of the Freie Gemeinde; he too lost his government job (as a jurist) because he refused to leave the dissenting religious community. He began a new career, learning masonry “from the ground up” and eventually becoming a very successful builder and property owner.

Käthe was born and grew up in Königsberg, the city where Immanuel Kant had preached the ideas of Enlightenment, and where her grandfather, theologian and preacher Julius Rupp, was removed from his post in the state church for his insistence on absolute freedom of conscience. Rupp subsequently founded the Freie Gemeinde (Free Congregation), a religious community based on Biblical ideas of a classless society, one which granted women an unusual degree of equality. Käthe’s mother was Rupp’s oldest daughter Katharina. Like her grandfather, Käthe’s father Carl Schmidt was a “republican,” a supporter of the 1848 revolution, as well as a member of the Freie Gemeinde; he too lost his government job (as a jurist) because he refused to leave the dissenting religious community. He began a new career, learning masonry “from the ground up” and eventually becoming a very successful builder and property owner.

Käthe was the fifth child of seven; the two older children had died early, as would the youngest. Käthe was closest to her younger sister Lise; like the von Lengefeld sisters Charlotte and Caroline a century earlier, Käthe and Lise swore never to marry and always remain together. The two wanted to become artists, and in their day women could not expect to combine marriage and a career. Käthe was allowed to read whatever books she wanted from the extensive family library, and she and Lise enjoyed an unusual degree of freedom to wander about the city. They especially loved to explore the docks and watch the sailors and dockworkers. Käthe later wrote: “If a whole period of my later work drew exclusively from the world of laborers, then the explanation can be found in those ramblings through the narrow, worker-filled commercial city.” (“Wenn meine späteren Arbeiten durch eine ganze Periode nur aus der Arbeiterwelt schöpften, so liegt der Grund dazu in jenen Streifereien durch die enge, arbeiterreiche Handelsstadt.” Knesebeck 11)

Her father encouraged her desire to become an artist – he believed she was not attractive enough to find a husband (!) – and paid for private art lessons for her from the age of 14, as well as supporting her art studies in Berlin and Munich. Women were not yet admitted to the official art academies and had to enroll in less well-regarded schools for female art students. After a year in Berlin, where her older brother Konrad was a student and where she studied drawing under Karl Stauffer-Bern, Käthe Schmidt spent another year painting and studying historical painting back in Königsberg with Professor Emil Neide, whom she now perceived as artistically retrograde. Contrary to her father’s expectations, Käthe had become secretly engaged to the medical student Karl Kollwitz in 1885, a fellow Social Democrat and member of the Freie Gemeinde. When the engagement was announced in 1888 father Schmidt was deeply disappointed, convinced that a woman could not successfully combine career and marriage; perhaps hoping to end the engagement, he sent his daughter far away from Königsberg and Karl to continue her studies in Munich (1888/89).

At the women’s art school in Munich Käthe Schmidt studied painting under Professor Ludwig Herterich and relished the the free and unconventional life of an art student: “The free style of the ‘paintgirls’ delighted me.” (“Der freie Ton der ‘Malweiber’ entzückte mich.” “Rückblick auf frühere Zeit” (1941) TB 738). Together with best friend Emma Beate Jeep and other art students, both male and female, she reveled in the famous celebrations and costume balls of Schwabing, Munich’s bohemian section. The group of women colleagues, including some in lesbian relationships, was an important aspect of her Munich experience. She later wrote of herself (1923):

At the women’s art school in Munich Käthe Schmidt studied painting under Professor Ludwig Herterich and relished the the free and unconventional life of an art student: “The free style of the ‘paintgirls’ delighted me.” (“Der freie Ton der ‘Malweiber’ entzückte mich.” “Rückblick auf frühere Zeit” (1941) TB 738). Together with best friend Emma Beate Jeep and other art students, both male and female, she reveled in the famous celebrations and costume balls of Schwabing, Munich’s bohemian section. The group of women colleagues, including some in lesbian relationships, was an important aspect of her Munich experience. She later wrote of herself (1923):

From my first infatuation on I’ve always been in love; it was a chronic condition, sometimes just a slight undertone, sometimes it grabbed me more powerfully. I wasn’t choosy in my choice of love-object. Sometimes it was women that I loved. The ones I was in love with seldom noticed. [….] Looking back over my life I must add that, although the inclination to the male sex was dominant with me, I nevertheless repeatedly felt an attraction to my own sex, which I mostly only much later understood how to interpret correctly. I also believe that bisexuality is almost a necessary prerequisite for artistic activity, that in any event the element of masculinity in me was helpful in my work.

(Von meiner ersten Verliebtheit an bin ich immer verliebt gewesen, es war ein chronischer Zustand, mal war es nur ein leiser Unterton, mal ergriff es mich stärker. In den Objekten war ich nicht wählerisch. Mitunter waren es Frauen, die ich liebte. Gemerkt haben es die, in welche ich verliebt war, selten. [….] Rückblickend auf mein Leben muss ich zu diesem Thema noch dazufügen, dass, wenn auch die Hinneigung zum männlichen Geschlecht die vorherrschende war, ich doch wiederholt auch eine Hinneigung zu meinem eigenen Geschlecht empfunden habe, die ich mir meist erst später richtig zu deuten verstand. Ich glaube auch, dass Bisexualität für künstlerisches Tun fast notwendige Grundlage ist, dass jedenfalls der Einschlag M. in mir meiner Arbeit förderlich war. – Erinnerungen, TB 725)

Given her exhilarating experience of independence, Käthe did begin to question her decision to marry. “The free life in Munich that I found so pleasing raised doubts in me as to whether I had done the right thing in committing myself so early though an engagement to marry. The free, independent life of an artist was very tempting.” (“Das freie, mir sehr wohl gefallende Leben in München erweckte Zweifel in mir, ob ich wohlgetan hätte, mich so frühzeitig durch Verlöbnis zu binden. Die freie Künstlerschaft lockte sehr.” Ibid 739).

Nonetheless she returned to Karl Kollwitz, married and settled with him in Berlin in 1891, where he opened a practice as “Kassenarzt” or physician for those insured as members of the tailors’ trade. The couple lived at Weißenbergstraße 25 (today Kollwitzstraße 59a) in the Prenzlauer Berg section of Berlin, a once upper-middle class neighborhood which had become increasingly working class. Since two rooms of the apartment were devoted to Karl’s medical practice Käthe had to use a neighbor’s living room – when available – for her studio; she was determined to continue her career as an artist, even after Hans and Peter were born in 1892 and 1894. She nonetheless also enjoyed motherhood, as Hans later remembered:

How mother lived with us! How she took part in our fantasy games […] in general play-acting was a very big part. She affirmed that and enjoyed it, as well as the occasional episodes of unintentional humor that resulted too.

(Wie hat die Mutter […] mit uns gelebt. Wie nahm sie Teil an unseren phantastischen Spielen […] überhaupt spielte die Schauspielerei eine große Rolle. Sie bejahte sie und hatte Freude an ihr, aber auch an mancher unfreiwilliger Komik, die sich dabei ergab. – 1948, in Knesebeck 28)

Karl Kollwitz saw up to 40 patients per day in his office in addition to making some 7 house calls. The antithesis of the typical patriarchal husband, he was absolutely devoted to Käthe and saw his role in serving her. Käthe benefitted from getting to know the working-class women who sat in her husband’s waiting room; they appealed to her aesthetic sense and some sat as models for her work. Through their stories she also gained a deeper insight into the hardships of proletarian life. Despite their demanding work and family obligations these were happy years for the couple. There would be times when Käthe confided to her diary that she did not feel as much love for her husband as he did for her and wished to be free of marriage and children; she also felt occasional very strong attraction to others (especially the Viennese journalist, editor, book dealer and arts promoter Hugo Heller), but she realized that an affair was not an option for her. In later years the marriage partners remained united in strong commitment and solidarity.

Käthe Kollwitz was decisively inspired in her artistic path by the privately performed play Die Weber (1893) of naturalist playwright Gerhart Hauptmann, which dramatized the unsuccessful revolt of Silesian weavers in 1844; it was considered so revolutionary that public performance was prohibited by the Kaiser. “This performance signified a milestone in my work.” (“Diese Aufführung bedeutete einen Markstein in meiner Abeit.” Rückblick, TB 740). Abandoning her previous project, she immediately began work on a series depicting the life and revolt of the weavers. The three lithographs and three etchings of “Ein Weberaufstand” were a technical and artistic challenge for her and were not completed until 1897. They brought her immediate recognition at the Große Berliner Kunstausstellung of 1898, and the jury selected her to receive a gold medal. Kaiser Wilhelm refused on the grounds that she was a woman (although the radical theme of her work surely also offended the conservative ruler):

Please, gentlemen, a medal for a woman – that would go too far. That would be the same as degrading every high award! Medals and decorations belong on the chests of deserving males.

(Ich bitte Sie, meine Herren, eine Medaille für eine Frau, das ginge doch zu weit. Das käme ja einer Herabwürdigung jeder hohen Auszeichnung gleich! Orden und Ehrenzeichnungen gehören auf der Brust verdienter Männer. - As quoted in Winterberg 145)

From now on Käthe Kollwitz was recognized as an important artist; she was invited to join the Berliner Secession in 1899 as one of three women among the 65 founding members.

Two trips to Paris, in 1901 and ’04, brought Kollwitz into contact with the latest developments in modern art, including the young Picasso’s choice of subjects from among the common people. She met Rodin and began studies in sculpture at the Académie Julian. In 1907 Kollwitz was awarded the Villa Romana Prize, which allowed her to spend several months in Florence. For her, however, the high point of this stay was a three-week journey on foot to Rome with the young Englishwoman Stan Harding; they traveled alone, frequently by night, and were often fed and sheltered by Italian peasants who took the two women for pilgrims. Only occasionally were they forced to take recourse to Stan’s revolver to scare off would-be molesters.

From 1903-08 Kollwitz worked on her second major graphic series “Bauernkrieg” (Peasants’ War), seven etchings based on historical research, illustrating the revolt and ultimate defeat of the German peasants against their overlords in 1525-26. Especially powerful is her representation of “Losbruch” (Outbreak), in which the monumental figure of “die Schwarze Anna” (Black Anna), the only historically documented woman of the war, whips up the revolutionary fervor of the repressed masses. The drastic scene “Vergewaltigt” (Raped) shows the violated body of a woman lying among rampant vegetation. With this dramatic series Kollwitz became known as “die Künstlerin der Revolution” (“the artist of the revolution” Kramer 47). Her work now focused predominantly on the lives of the working class and poor, the oppressed of her society. In part this was the result of her own political convictions and social empathy; in part because she had always been drawn to proletarian figures as aesthetically more interesting, indeed beautiful.

The actual reason, however, why I chose to represent working class life almost exclusively from this point on was that the motifs I chose from this sphere simply and unconditionally gave me what I experienced as beautiful. Beautiful for me […] was the generosity of movement of the people. People from the middle class had no aesthetic appeal for me at all. The entire bourgeois way of life appeared pedantic to me. By contrast the proletariat seemed to have much more on the ball. Only much later did I fully recognize the fate of the proletariat. Unsolved problems like prostitution, unemployment tormented and worried me and added to my reasons for portraying the underclass; and by repeatedly representing them I found relief, or a way of enduring life.

(Das eigentliche Motiv aber, warum ich von jetzt an zur Darstellung fast nur das Arbeiterleben wählte, war, weil die aus dieser Sphäre gewählten Motive mir einfach und bedingungslos das gaben, was ich als schön empfand. Schön war für mich [...] die Großzügigkeit der Bewegungen im Volke. Ohne jeden Reiz waren mir Menschen aus dem bürgerlichen Leben. Das ganze bürgerliche Leben erschien mir pedantisch. Dagegen einen großen Wurf hatte das Proletariat. Erst viel später […] erfasste mich mit ganzer Stärke das Schicksal des Proletariats […]. Ungelöste Probleme wie Prostitution, Arbeitslosigkeit, quälten und beunruhigten mich und wirkten mit als Ursache dieser meiner Gebundenheit an die Darstellung des niederen Volkes, und ihre immer wiederholte Darstellung öffnete mir ein Ventil oder eine Möglichkeit, das Leben zu ertragen. – “Rückblick” in TB 741)

In 1908 and ’09 Kollwitz provided 14 charcoal drawings of proletarian life for the left-liberal Munich satirical magazine Simplizissimus; these drawings, many showing women and mothers, reveal the increasing socially-critical stance of her work.

In 1908 and ’09 Kollwitz provided 14 charcoal drawings of proletarian life for the left-liberal Munich satirical magazine Simplizissimus; these drawings, many showing women and mothers, reveal the increasing socially-critical stance of her work.

With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 Germany was swept up in patriotic fever; both Kollwitz sons were eager to join the army and even sacrifice their lives for the “Fatherland.” As Social Democrats Karl and Käthe were opposed to the war. Käthe, however, allowed herself to be swayed by Peter’s idealistic enthusiasm and persuaded her husband to give the required permission for the 18-year-old to vounteer. He was dispatched to Belgium and was almost immediately killed, among the first of millions of deaths. Käthe was devastated, but only gradually came to distance herself from the idea of a patriotic “Heldentod” (hero’s death), which she had embraced out of loyalty to Peter and his idealism. Processing her reflections in her diary, she questioned the idea of such sacrifice, made by the youth of England, France and Russia as well as Germany. She wrote in 1916: “The result was a raging against each other, Europe’s deprivation of its most valuable possession. Have our youth been betrayed all these years?” (“Die Folge war, das Rasen gegeneinander, die Verarmung Europas am Allerschönsten. Ist also die Jugend in all diesen Jahren betrogen worden?” – in Knesebeck 66; find Q in TB). By 1918, when the war was clearly lost, Kollwitz publicly opposed those intellectuals like Richard Dehmel who urged continuing the fight to the bitter end. In an open letter she argued that enough young lives had been lost, finishing with a quotation from her beloved Goethe: “Saatfrüchte sollen nicht vermahlen werden.” (Grain for the planting must not be ground up).

With many discouraging interruptions and shifting artistic variations Kollwitz dedicated herself for years to memorializing her son – and ultimately all the fallen volunteers of the war. Begun in 1914 with her dead soldier son as centerpiece, the final memorial took a different form: a monumental sculpture of two grieving parents. Finally completed in 1931, it was installed the following year at the cemetery of Roggevelde in Flanders, where Peter lay buried. Later, when Peter's grave was moved to the nearby Vladslo German war cemetery, the statues were also moved.

Beginning in 1915 Kollwitz also explored her responses to the war in the series “Krieg” (War). Strongly affected and influenced by the woodcuts of Ernst Barlach in 1920, she chose this medium, a favorite of the Expressionists, for her project, which presents in seven images the pain and suffering she had experienced. Starting with the “sacrifice” of a mother offering her newborn to the world, she moves to scenes of young enlistees being swept into battle by the drummer Death, of grieving parents, mothers, widows and finally “das Volk.” The series was completed in 1922.

With the coming of the Weimar Republic in 1919 Kollwitz could be given official, public recognition; she was admitted to the Prussian Akademie der Künste (Academy of Arts) as the first woman and given the title of Professor. She also participated actively in political demonstrations and protests and was increasingly called upon to produce art in support of democratic and proletarian causes. After the murders of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht in 1919 Kollwitz produced a woodcut memorializing Liebknecht. Her posters against war (“Nie wieder Krieg!”) and against the anti-abortion Paragraph 218 (1923-24) have survived to inspire movements of the 1960’s -1980’s. As a committed pacifist Kollwitz worked together with Albert Einstein and Romain Rolland on behalf of European understanding during the chaotic early years of the Weimar Republic. She saw her artistic representations neither as art for art’s sake nor as propaganda, but rather as aimed at helping people grapple with with the issues of the day:

I accept the fact and agree that my art has a [social] purpose. I want to have an effect in these times when people are so at a loss and in need of help.

(Ich bin einverstanden damit, das meine Kunst Zwecke hat. Ich will wirken in dieser Zeit, in der die Menschen so ratlos und hilfsbedürftig sind. – 4. Dezember 1922, TB 542)

Kollwitz’ 60th birthday in 1927 marked the high point of her recognition; she received more than 500 congratulatory letters and telegrams, including from high government dignitaries. Her fame had spread beyond Germany to Russia, China and the US, as well as other European countries. In 1929 she was awarded the highest honor of the Weimar Republic, the Order “Pour le Mérite,” once again as the first woman recipient.

In 1933, however, her reputation as a supporter of Social Democracy and her early warnings and protests against the new Hitler regime brought about her forced exit from the Akademie der Künste; author Heinrich Mann experienced the same fate. Kollwitz’ works were gradually removed from museums and exhibitions. Following an article published in the Soviet Union that was unflattering concerning her treatment by the Nazi government she was visited by the Gestapo and threatened with internment in a concentration camp. But she was able to share a communal studio and continue working, completing the lithograph series “Tod” (Death) and sculptures such as “Mutter mit zwei Kindern” and “Turm der Mütter” (Tower of Mothers). Meanwhile, although her works were no longer shown in Germany, they gained new currency in the USA and Switzerland, as emigrant families sold their art to raise money.

Karl Kollwitz died in 1940; Käthe gave up her studio space and withdrew to her Berlin apartment. In 1941, as war again raged, she created her signature lithograph of an anxious but determined mother protecting three young boys under her coat; it bears the title that had come to be her testament: ““Saatfrüchte sollen nicht vermahlen werden.” (Grain for the planting must not be ground up). Yet tragically, despite her passionate belief in this commandment, her grandson Peter, the namesake of his fallen uncle, was killed in Russia in 1942. As Berlin came under attack from Allied bombing in 1943 Käthe Kollwitz was evacuated to Nordhausen to shelter with other refugees at the home of sculptor Margarete Böning. Soon afterwards the Kollwitz house was hit by a bomb and went up in flames. When Nordhausen also became too dangerous, in 1944, she was invited to live in a farmhouse in Moritzburg near Dresden by Prince Ernst Heinrich of Sachsen, an admirer and collector of her work. Here the increasingly frail artist was cared for by her granddaughter Jutta Kollwitz until her death just before the end of the war, on 22 April 1945.

Karl Kollwitz died in 1940; Käthe gave up her studio space and withdrew to her Berlin apartment. In 1941, as war again raged, she created her signature lithograph of an anxious but determined mother protecting three young boys under her coat; it bears the title that had come to be her testament: ““Saatfrüchte sollen nicht vermahlen werden.” (Grain for the planting must not be ground up). Yet tragically, despite her passionate belief in this commandment, her grandson Peter, the namesake of his fallen uncle, was killed in Russia in 1942. As Berlin came under attack from Allied bombing in 1943 Käthe Kollwitz was evacuated to Nordhausen to shelter with other refugees at the home of sculptor Margarete Böning. Soon afterwards the Kollwitz house was hit by a bomb and went up in flames. When Nordhausen also became too dangerous, in 1944, she was invited to live in a farmhouse in Moritzburg near Dresden by Prince Ernst Heinrich of Sachsen, an admirer and collector of her work. Here the increasingly frail artist was cared for by her granddaughter Jutta Kollwitz until her death just before the end of the war, on 22 April 1945.

In 1993, on the initiative of Chancellor Hemut Kohl, Kollwitz’ small, intimate “Mother with Dead Son” or “Pietà” (1938) was reproduced in bronze as a much larger sculpture and installed in Berlin’s Neue Wache as a memorial to the victims of war and totalitarian brutality.

Author: Joey Horsley

Literature & Sources

For images, links and additional resources, please see the German version.

Bonus-Jeep, Beate. 1948. 60 Jahre Freundschaft mit Käthe Kollwitz. Boppard.

Kearns, Martha. 1976. Käthe Kollwitz. Woman and Artist. New York: Feminist Press.

Knesebeck, Alexandra von dem. 2016. Käthe Kollwitz. Köln: Wienand Verlag.

Kollwitz, Käthe. 2012. Die Tagebücher 1908-1943. Herausgegeben und mit einem Nachwort versehen von Jutta Bohnke-Kollwitz. München: btb Verlag. (=TB)

Krahmer, Catherine. 1981. Käthe Kollwitz in Selbstzeugnissen und Bilddokumenten (= Rowohlts Monographien 294). Reinbeck bei Hamburg: Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag.

Schymura, Yvonne. 2014. Käthe Kollwitz 1867-2000. Biographie und Rezeptionsgeschichte einer deutschen Künstlerin. Essen: Klartext.

Schymura, Yvonne. September 2016. Käthe Kollwitz. Die Liebe, der Krieg und die Kunst. Eine Biographie. München: Beck.

Winterberg, Yury und Sonya Winterberg. 2015. Kollwitz. Die Biographie. München: Bertelsmann.

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.