(Ruth Keller [Pseudonym])

Born 25 June 1926 in Klagenfurt, Austria

Died 17 October 1973 in Rome

Austrian poet and author

45th Anniversary of death on 17 October 2018

Biography • Quotes • Literature & Sources

Biography

“What actually is possible, however, is transformation. And the transformative effect that emanates from new works leads us to new perception, to a new feeling, new consciousness.”

This sentence from Ingeborg Bachmann’s Frankfurt Lectures on Poetics (1959-60) can also be applied to her own self-consciousness as an author, and to the history of her reception. Whether in the form of lyric poetry, short prose, radio plays, libretti, lectures and essays or longer fiction, Bachmann’s œuvre had as its goal and effect “to draw people into the experiences of the writers,” into “new experiences of suffering.” (GuI 139-140). But it was especially her penetrating and artistically original representation of female subjectivity within male-dominated society that unleashed a new wave in the reception of her works.

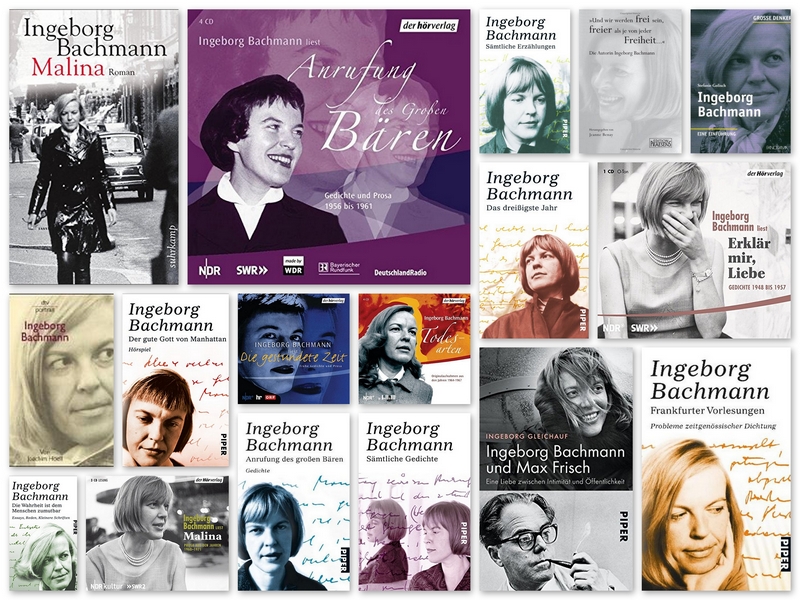

Although Bachmann’s spectactular early fame derived from her lyric poetry (she received the prestigious Prize of the Gruppe 47 in 1954), she turned more and more towards prose during the 1950’s, having experienced severe doubts about the validity of poetic language. The stories in the collection Das dreißigste Jahr (The Thirtieth Year; 1961) typically present a sudden insight into the inadequacy of the world and its “orders” (e.g. of language, law, politics, or gender roles) and reveal a utopian longing for and effort to imagine a new and truer order. The two stories told from an explicitly female perspective, “Ein Schritt nach Gomorrha” (“A Step towards Gomorrah”) and “Undine geht” (“Undine Goes/Leaves”), are among the earliest feminist texts in postwar German-language literature. Undine accuses male humanity of having ruined not only her life as a woman but the world in general: “You monsters named Hans!” In her later prose (Malina 1971; Simultan 1972; and the posthumously published Der Fall Franza und Requiem für Fanny Goldmann) Bachmann was again ahead of her time, often employing experimental forms to portray women as they are damaged or even destroyed by patriarchal society, in this case modern Vienna. Here one sees how intertwined Bachmann’s preoccupation with female identity and patriarchy is with her diagnosis of the sickness of our age: “I’ve reflected about this question already: where does fascism begin? It doesn’t begin with the first bombs that were dropped…. It begins in relationships between people. Fascism lies at the root of the relationship between a man and a woman….”(GuI 144)

As the daughter of a teacher and a mother who hadn’t been allowed to go to university, Bachmann enjoyed the support and encouragement of both parents; after the war she studied philosophy, German literature and psychology in Innsbruck, Graz and Vienna. She wrote her doctoral dissertation (1950) on the critical reception of Heidegger, whose ideas she condemned as “a seduction … to German irrationality of thought” (GuI 137). From 1957 to 1963, the time of her troubled relationship with Swiss author Max Frisch, Bachmann alternated between Zurich and Rome. She rejected marriage as “an impossible institution. Impossible for a woman who works and thinks and wants something herself” (GuI 144).

From the end of 1965 on Bachmann resided in Rome. Despite her precarious health—she was addicted to pills for years following a faulty medical procedure—she traveled to Poland in 1973. She was just planning a move to Vienna when she died of complications following an accidental fire.

(Original of the shorter version from Pusch/Gretter, Berühmte Frauen: 300 Portraits, 1999)

Author: Joey Horsley

Quotes

I myself am a person who has never resigned myself, who is absolutely never resigned, who can’t imagine it at all. I simply observe, and I observe in so many people, and often very quickly, a resignation that terrifies me, that’s it. (Interview with Volker Zielke, 7.Oct 1972. (GuI 118/9)

Nonetheless even in capitulation there is still hope, and this hope of human beings never ends, will never end. (GuI 128)

And I don’t believe in this materialism, in this consumer society, in this capitalism, in this outrageous horror that happens / takes place here…. I really do believe in something, and I call it “a day will come.” And one day it will come. Well, probably it won’t come, since they’ve always destroyed it for us…. It won’t come, and I believe in it anyway. Because if I can’t believe in it anymore then I can’t write anymore either. (June 1973. GuI 145)

Literature & Sources

GuI = Bachmann, Ingeborg. Wir müssen wahre Sätze finden. Gespräche und Interviews. München: Piper 1983 (3. Auflage 1991).

Achberger, Karen. 1995. Understanding Ingeborg Bachmann. Columbia, S.C. : University of South Carolina Press.

Bachmann, Ingeborg. 1993. Werke in vier Bänden. Hg. von Christine Koschel, Inge von Weidenbaum und Clemens Münster. München. Serie Piper 1700.

Bachmann, Ingeborg. 1993. Werke in vier Bänden. Hg. von Christine Koschel, Inge von Weidenbaum und Clemens Münster. München. Serie Piper 1700.

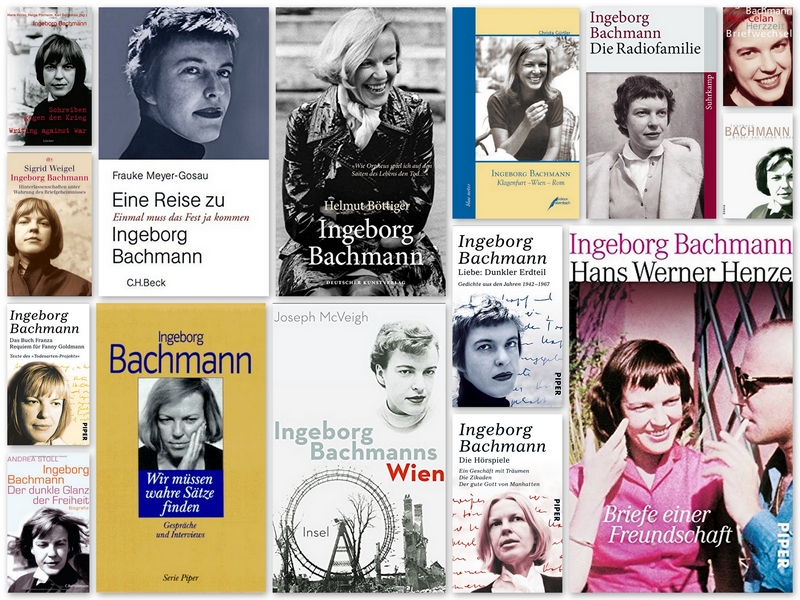

Bachmann, Ingeborg & Hans Werner Henze. 2004. Briefe einer Freundschaft; Hg. Hans Höller; Vorwort von Hans Werner Henze. München. Piper.

Beicken, Peter. 1988. Ingeborg Bachmann. München. Beck'sche Reihe Autorenbücher (BsR 605).

Beicken, Peter. 1988. Ingeborg Bachmann. München. Beck'sche Reihe Autorenbücher (BsR 605).

Höller, Hans. 1987. Ingeborg Bachmann. Das Werk. Von den frühesten Gedichten bis zum “Todesarten”-Zyklus. Frankfurt/M.

Höller, Hans. 1999. Ingeborg Bachmann. Reinbek bei Hamburg. rororo monographie.

Lennox, Sara. „Ingeborg Bachmann.”The Literary Encyclopedia. 18 Sep. 2004. The Literary Dictionary Company. 19 June 2006.

Lennox, Sara. „Ingeborg Bachmann.”The Literary Encyclopedia. 18 Sep. 2004. The Literary Dictionary Company. 19 June 2006.

Text + Kritik. Sonderband: Ingeborg Bachmann. 1984. Gastredaktion Sigrid Weigel. Darin: Otto Bareiss: Vita Ingeborg Bachmann, S. 180-185; Otto Bareiss: Auswahlbibliographie 1953-1983/84, S. 186-215. München.

Weigel, Sigrid. 1999. Ingeborg Bachmann: Hinterlassenschaft unter Wahrung des Briefgeheimnisses. Wien. Zsolnay.

For additional references and many weblinks, see the German page.

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.