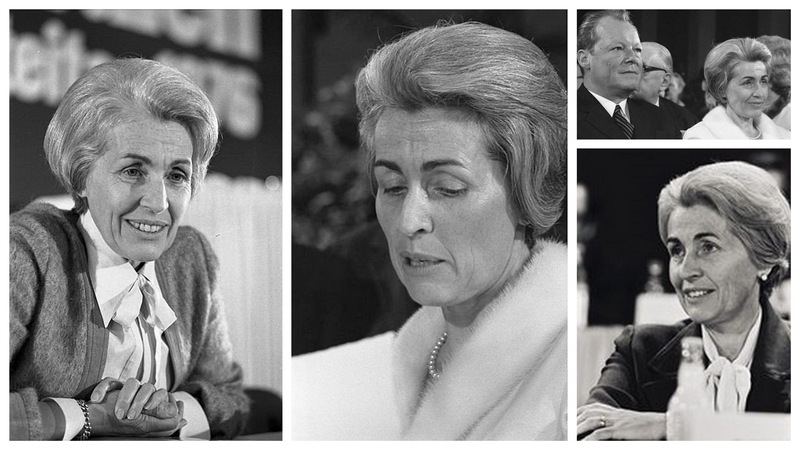

Biographies Hildegard Hamm-Brücher

((Dr. Dr. h.c. Hildegard Hamm-Brücher, née Brücher))

Born May 11, 1921 in Essen

Died December 7, 2016 in Munich

German politician (FDP), chemist, editor, journalist

100. birthday May 11, 2021

Biography • Quotes • Weblinks • Literature & Sources

Biography

“Gesinnungsliberale” (“liberal of conscience”) and “grande dame of the Liberals” are labels that were attached to Hildegard Hamm-Brücher decades ago. (The “liberal,” or Free Democratic Party, is a political party in Germany.) Democracy – both as a political system and as a way of life – was her primary passion; partisan political interests were secondary for her. She was the first woman to run for the office of President of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Hildegard Brücher was the third of five children born to a factory owner’s daughter and a business executive. She spent the early years of her life in Berlin. When she was eleven years old, her parents died and she was raised along with three siblings by her grandmother, Else Pick, in Dresden. Hildegard Brücher had to leave boarding school in Salem after just one year because of her “non-Aryan” heritage. Her grandmother’s family had long ago been baptized and assimilated in the Protestant church, but this was of no concern to the Nazis. Else Pick took her own life in 1942, shortly before she was to be deported to a concentration camp.

Because Hildegard Brücher was considered a “Halbjüdin” (“half-Jew”), she could only complete her Abitur (school-leaving exam and university entrance qualification) in a roundabout way. Starting in 1940, she studied chemistry in Munich – including with the Nobel laureate Heinrich Wieland, who arranged for special permission for her to enroll at the university and under whose supervision she received her doctorate in 1945. During her studies, she became acquainted with the siblings Hans and Sophie Scholl and other members of the White Rose resistance group. She escaped imminent arrest by the Gestapo through the intervention of Heinrich Wieland.

After the war ended, Hildegard Brücher worked for three years as an editor of Die Neue Zeitung in Munich. During an interview in 1948 with Theodor Heuss, who would be elected Germany’s first president a year later, she was persuaded to join the FDP (Free Democratic Party, or Liberals). That same year, she became the youngest elected representative to the Munich city council, of which she was a member for the next six years. In 1956, she married Erwin Hamm, a city council member for the Christian Social Union (CSU) and – unusually for the time – adopted the double surname Hamm-Brücher. Their children Florian and Verena were born in 1954 and 1959.

From 1950 to 1966, Hildegard Hamm-Brücher was a member of the Bavarian state assembly. In 1964, she spearheaded the campaign calling for the resignation of the Bavarian minister of education and culture, Theodor Maunz; during the Nazi era he had written legal commentaries justifying anti-Jewish regulations and statutes as lawful, and even after the war he considered the Gestapo as “unobjectionable from a legal point of view.” Two years later, Hamm-Brücher organized the first referendum in Bavaria against denominational schools and in favor of secular schools; the campaign was not successful, however, until a second attempt in 1969. She also campaigned for comprehensive education reform. From 1967-69, she was a state secretary in the ministry of education and cultural affairs in the state of Hesse; she subsequently joined the Social Democratic-Liberal coalition government under Chancellor Willy Brandt as a state secretary in the Federal Ministry of Education. In 1972, she returned to the Bavarian state parliament as a representative, where she became chairwoman of the FDP parliamentary group.

From 1976 (until 1990), Hildegard Hamm-Brücher was a member of the Bundestag. She was a strong supporter of the Social Democratic-Liberal (SPD-FDP) coalition. As a state secretary in the Federal Foreign Ministry, she was responsible for foreign cultural policy. With her speech opposing the vote of no confidence in Chancellor Helmut Schmidt in the autumn of 1982 – which also received much public attention – she broke ranks with her own parliamentary faction but was unable to prevent its support from shifting to a new coalition government with the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) under Helmut Kohl. Unlike some other critics of this move, however, she remained in the FDP.

From 1976 (until 1990), Hildegard Hamm-Brücher was a member of the Bundestag. She was a strong supporter of the Social Democratic-Liberal (SPD-FDP) coalition. As a state secretary in the Federal Foreign Ministry, she was responsible for foreign cultural policy. With her speech opposing the vote of no confidence in Chancellor Helmut Schmidt in the autumn of 1982 – which also received much public attention – she broke ranks with her own parliamentary faction but was unable to prevent its support from shifting to a new coalition government with the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) under Helmut Kohl. Unlike some other critics of this move, however, she remained in the FDP.

Hamm-Brücher advocated in vain for a more rigorous party finance law and for parliamentary reform; she called for increased participatory democracy and criticized factionalism, party bureaucracy and a lack of legislative awareness among elected representatives. In 1994, she became the first woman to run for the office of Federal President but dropped out after the second round of voting once it became clear that the CDU candidate, Roman Herzog, was also backed by members of her own party.

In protest against the coalition statement of the Bavarian FDP in favor of the CSU in the state parliamentary election, Hildegard Hamm-Brücher resigned from the state FDP in 1998, while remaining a member of the national party. Until 2001, she chaired the Theodor Heuss Foundation, which she co-founded and which awards the annual Theodor Heuss Prize for civil courage and civic commitment.

Hildegard Hamm-Brücher’s many accolades included the Bavarian Constitution Medal in gold and the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (Grand Cross of Merit with Star and Sash) as well as an honorary doctorate from Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena. In 1995, she became the first woman ever to be named an honorary citizen of the city of Munich. In the fall of 2002, she resigned from the national FDP after 54 years, due to continued rightwing-populist and antisemitic statements made by party vice-chair Jürgen W. Möllemann and tolerated by FDP chairman Guido Westerwelle.

(Text from 2010; transl. 2021 by Julie Niederhauser)

For additional information please consult the German version.

Author: Christine Schmidt

Quotes

“I believe: if it is true that the natural resources, the energy and food reserves of our world, are not inexhaustible, then it is really high time to enable more and more people to channel their intellectual energies and their behavior towards the preservation of our world instead of towards its over-exploitation.” […]

“A democratic meritocracy most certainly cannot be ruined by giving more people better educational opportunities and therefore better opportunities in life…”

(From her book »Bildung ist kein Luxus« / “Education Is Not a Luxury,” 1976)

“I think that neither of them deserved this: Helmut Schmidt to be brought down without a vote of the electorate and you, Helmut Kohl, to attain the chancellorship without a vote of the electorate. There is no doubt that both of these processes are constitutional. But in my view, they have the odium of violated democratic decency.”

(From the opposition speech against the motion of censure of Chancellor Helmut Schmidt brought by the CDU/CSU and FDP parliamentary groups on October 1, 1982)

“To be sure, no one can tell anyone precisely how to be ‘a representative of the whole people.’ But it is equally sure that it certainly cannot mean being exclusively a representative of party interests.” […]

“In any case, the political conscience of women, I find again and again, is generally more sensitive, and this is independent of their party affiliation or their feminine self-image. This also explains why female politicians for the most part enjoy greater trust among the public than their male colleagues. For this reason alone, the demand that more women belong in parliaments is extremely justified.”

From her book »Der Politiker und sein Gewissen« / “The Politician and His Conscience,” 1983)

“It is traditionally male principles which are concerned with power and advantage rather than balance and fairness. This cannot but result in the atrophy of mental powers. ‘Partnership’ is spoken of at best in after-dinner speeches.”

(From an address to women’s organizations in Lucerne, 1985)

“That is why I am against quotas, because I do not believe that they really help. No woman can avoid her own individual emancipation – given the legal prerequisites which enable her access in the first place. But the actual steps in asserting oneself, in getting involved, these things every woman must do herself.”

(Interview in »Zeugen des Jahrhunderts« / “Witnesses of the Century,” 1993)

Links

Internet Movie Database: Hildegard Hamm-Brücher. Films.

Available online at http://www.imdb.com/name/nm1863105/, checked on 4/24/2021.

Katalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Hamm-Brücher, Hildegard, 1921-. Publications.

Available online at http://d-nb.info/gnd/118545396, checked on 4/24/2021.

Wikimedia Commons: Hildegard Hamm-Brücher. Fotos aus dem Bundesarchiv.

Available online at http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Hildegard_Hamm-Br%C3%BCcher?uselang=en, checked on 4/24/2021.

Literature & Sources

Sources

Hamm-Brücher, Hildegard (1986): Kämpfen für eine demokratische Kultur. Texte aus 4 Jahrzehnten. Vorwort von Helmut Schmidt. München, Zürich. Piper. (Serie Piper, 624) ISBN 3-492-10624-2. (Eurobuch-Suche | WorldCat-Suche)

Hamm-Brücher, Hildegard (1981): Mut zur Politik. Gespräch mit Carola Wedel in der Reihe »Zeugen des Jahrhunderts«. . Herausgegeben von Ingo Hermann Göttingen. Lamuv. 1993. (Zeugen des Jahrhunderts) ISBN 3-88977-325-7. (Amazon-Suche | Eurobuch-Suche | WorldCat-Suche)

Hamm-Brücher, Hildegard (1996): Freiheit ist mehr als ein Wort. Eine Lebensbilanz. München. Dt. Taschenbuch-Verl. 1997. (dtv, 30644) ISBN 3-423-30644-0. (Amazon-Suche | Eurobuch-Suche | WorldCat-Suche)

Hamm-Brücher, Hildegard (1997): »Zerreißt den Mantel der Gleichgültigkeit«. Die »Weiße Rose« und unsere Zeit. . Herausgegeben von Wilhelm von Sternburg Berlin. Aufbau. (Aufbau-Taschenbücher, 8515 : Aufbau-Thema) ISBN 3-7466-8515-X. (Amazon-Suche | Eurobuch-Suche | WorldCat-Suche)

Hamm-Brücher, Hildegard (2001): Erinnern für die Zukunft. Ein zeitgeschichtliches Nachlesebuch 1991 bis 2001. München. Dt. Taschenbuch-Verl. (dtv, 24254 : Premium) ISBN 3-423-24254-X. (Amazon-Suche | Eurobuch-Suche | WorldCat-Suche)

Salentin, Ursula (1987): Hildegard Hamm-Brücher. Der Lebensweg einer eigenwilligen Demokratin. Freiburg. Herder. (Herderbücherei) ISBN 3-451-08315-9. (Amazon-Suche | Eurobuch-Suche | WorldCat-Suche)

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.