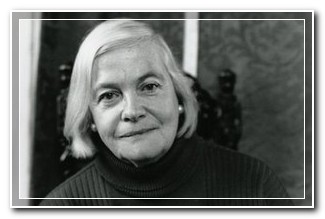

(Hélène Serafia (Hella) Haasse; Hélène Serafia Lelyveld-Haasse [Ehename]; C. J. van der Sevensterre [Pseudonym])

born February 2, 1918 in Weltevreden, Batavia, Dutch India, (since 1945/49 Djakarta, capital of the Republic of Indonesia)

died September 29, 2011 in Amsterdam

Dutch writer

10th anniversary of death on September 29, 2021

Biography • Literature & Sources

Biography

“Writing is my way of being present”. When Hella S. Haasse - her nom de plume - described herself in this way in 2005, she was looking back on 60 years of “presence,” during which she had created some 60 works[I.], among them mainly novels, but also plays and literary reflections. She was active for two more years before old age and finally a brief illness prevented her from continuing to work.

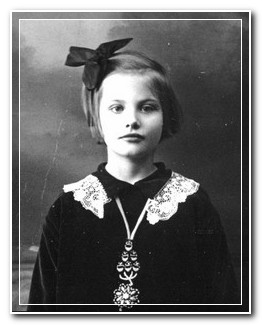

Haasse[II] was the eldest child of the concert pianist and composer Katharina Diehm Winzenhöhler and Willem Hendrik Haasse, a senior official in the Dutch-Indian colonial administration who worked as a tax investigator. Under a pseudonym, he wrote more than a dozen crime novels. For most of her childhood and adolescence, Haasse lived in the Dutch Indies (“Indië,” as opposed to the Indian subcontinent, which is called “India”).  In 1920/21, while her father was on home leave, she attended preschool in Holland, then Catholic elementary school in Surabaja, East Java. In 1924, she accompanied her mother to Davos, Switzerland, where she was treated in a sanatorium. She went to school with the nuns. Afterwards she lived with her grandmother in Heemstede, NL, and in the children's home in Baarn. She began writing stories at the age of eight. In 1928 she returned with her parents to Batavia, where she attended the “middelbare school” (grammar school) until graduating in 1938.

In 1920/21, while her father was on home leave, she attended preschool in Holland, then Catholic elementary school in Surabaja, East Java. In 1924, she accompanied her mother to Davos, Switzerland, where she was treated in a sanatorium. She went to school with the nuns. Afterwards she lived with her grandmother in Heemstede, NL, and in the children's home in Baarn. She began writing stories at the age of eight. In 1928 she returned with her parents to Batavia, where she attended the “middelbare school” (grammar school) until graduating in 1938.

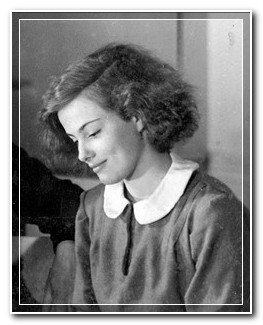

In the same year she finally moved to Amsterdam for a long time to study Scandinavian linguistics and literature. She now lived without family, because her father was interned until the end of the war in 1942 after the invasion of the Indonesian archipelago by the Japanese, like tens of thousands of Dutch people. Her first attempts at writing also date from this time, and it was at the satirical-critical student newspaper Propria Cures, to which she wrote only one contribution, that she met her future partner Jan van Lelyveld in 1939. In 1941 she broke off her studies and enrolled at the Amsterdamse Toneelschool, the academy for the stage professions. To make a living, she became a member of the “Centraal Toneel,” a theater society by Nazi occupier's grace, including forced membership in the Nederlandsche Kultuurkamer, also NS.

On February 18, 1944, she married Jan van Lelyveld and gave up her stage career, but continued to write for the theater. By 1951 she had given birth to three daughters, the eldest of whom died as early as 1947. In 1945 her literary debut appeared, a book of poems called “Stroomversnelling” (Rapids, also used metaphorically), and in 1947 the feminist story “Clothes Make the Woman.” In 1948, her book “Oeroeg” (Engl. The Black Lake, 1994) was published as a Book Week gift. In this annual custom, Dutch booksellers invite young authors to write a book at association expense to be given away to book buyers at Book Week. Oeroeg brought her an immediate literary breakthrough. She was invited twice more in this way: in 1959 with “Dat weet ik self niet” and in 1994 with the autobiographical book “Transit”.

In 1969 and 1976, she traveled to Java again to satisfy her longing. Afterwards she formulated the realization: “Now I have seen it, I only now understand that I am a stranger, even if it is the country where I was born.”[III] In 1981 she moved to France with her husband. She spent the last years of her life back in Amsterdam. She was indifferent to digital media and the usefulness and information value of the Internet, but three days after her 90th birthday she herself opened the virtual Hella Haasse Museum, wherein she published her entire personal archive, in it documents, family photos, letters as well as book fragments. In 2017 the museum was taken off the net and was not continued.[IV.]

Of the more than thirty novels, only a few can be cited and considered here that have received particular attention or have been declared important by Hella Haasse herself. Oeroeg (pronounced “Urúkh”) is about a Sundanese (West Javanese) boy of that name and his best friend, the unnamed son of a colonial estate manager and first-person narrator. After Indonesia's independence and the so-called police actions - the four-year brutal as well as futile attempt by the Dutch to prevent it and regain sovereignty from the Japanese - he sets out to find points of connection from the time of this boyhood friendship. Already in this novella Haasse works with many flashbacks and a highly complex narrative structure, which she constructs with increasing virtuosity in her later work. The essential theme here is the contrasts and consequences of Dutch colonial history, portrayed through the deeds and thoughts of the characters involved, as in two later “Indian” novels, historical-documentary in “Heren van de thee” 1992 (Engl: The Tea Barons 1995) and Sleuteloog (“Keyhole”; Engl: The Indonesian Secret) 2002. In this novel, generally regarded as the crowning achievement of her oeuvre, a Dutch art historian searches for the traces and scenes of her memories in Java. The key lies in her cassette full of documents, but she has lost the key. As the narrative progresses, more and more facts come to light, some of which her memory has suppressed, so that the reader eventually knows more of the truth than she does.

Of the more than thirty novels, only a few can be cited and considered here that have received particular attention or have been declared important by Hella Haasse herself. Oeroeg (pronounced “Urúkh”) is about a Sundanese (West Javanese) boy of that name and his best friend, the unnamed son of a colonial estate manager and first-person narrator. After Indonesia's independence and the so-called police actions - the four-year brutal as well as futile attempt by the Dutch to prevent it and regain sovereignty from the Japanese - he sets out to find points of connection from the time of this boyhood friendship. Already in this novella Haasse works with many flashbacks and a highly complex narrative structure, which she constructs with increasing virtuosity in her later work. The essential theme here is the contrasts and consequences of Dutch colonial history, portrayed through the deeds and thoughts of the characters involved, as in two later “Indian” novels, historical-documentary in “Heren van de thee” 1992 (Engl: The Tea Barons 1995) and Sleuteloog (“Keyhole”; Engl: The Indonesian Secret) 2002. In this novel, generally regarded as the crowning achievement of her oeuvre, a Dutch art historian searches for the traces and scenes of her memories in Java. The key lies in her cassette full of documents, but she has lost the key. As the narrative progresses, more and more facts come to light, some of which her memory has suppressed, so that the reader eventually knows more of the truth than she does.

In the winter of 1944/45, as a result of the German occupation, there was a terrible and deadly famine in the west and north of Holland. At this time Haasse began her work on “Het woud der verwachting” (Engl. In a dark wood wandering, 1989) about the life of Charles of Orleans, nobleman and poet, who always stood up for peace, although he was in English captivity for 25 years. In 1949 this novel was published, on which she had worked for five years so that no formulation was left standing with which she was not satisfied. Even in this first of her historical novels, she repeatedly breaks through the novel structure in search of clues to answers that ultimately fail to materialize, in order to make it clear that neither historiography nor literature alone offers a complete picture.

Considered her most important historical novel, “De scharlaken stad” 1952 (Engl The scarlet city. A novel of 16th-century Italy, 1952) is an exciting game of confusion about the identity of Giovanni Borgia (or Farnese?) against the backdrop of the intertwining of power and the game of intrigues in Rome around 1500. As always, Haasse offers few explanations or opinions, but leaves the reader to unravel. In 1966, the novel “Een nieuwer testament” (Engl. Threshold of fire. A novel of fifth century Rome, 1993) was published. The story takes place in Rome on July 5 and 6, 417. The two main characters know each other from their childhood together on the Nile. Ten years earlier, Hadrian, now a defendant for Christian activities, had banished his current judge from Rome. The past interferes more and more embarrassingly in the present trial, at a time when Rome's religious future is still entirely open. The tragedy takes its course. In her historical works after 1976, Haasse increasingly devotes herself to novelistic documentation, incorporating real letters and archival materials, for example in “Mevrouw Bentinck, of, Onvereinigbaarheid van karakter: een ware geschiedenis” 1978 (“I always contradict: the irrepressible life of Countess Bentinck,” 1997). As so often, the German book title does not seem fortunate: “Eine wahre Geschichte,” for example, is simply omitted.

Considered her most important historical novel, “De scharlaken stad” 1952 (Engl The scarlet city. A novel of 16th-century Italy, 1952) is an exciting game of confusion about the identity of Giovanni Borgia (or Farnese?) against the backdrop of the intertwining of power and the game of intrigues in Rome around 1500. As always, Haasse offers few explanations or opinions, but leaves the reader to unravel. In 1966, the novel “Een nieuwer testament” (Engl. Threshold of fire. A novel of fifth century Rome, 1993) was published. The story takes place in Rome on July 5 and 6, 417. The two main characters know each other from their childhood together on the Nile. Ten years earlier, Hadrian, now a defendant for Christian activities, had banished his current judge from Rome. The past interferes more and more embarrassingly in the present trial, at a time when Rome's religious future is still entirely open. The tragedy takes its course. In her historical works after 1976, Haasse increasingly devotes herself to novelistic documentation, incorporating real letters and archival materials, for example in “Mevrouw Bentinck, of, Onvereinigbaarheid van karakter: een ware geschiedenis” 1978 (“I always contradict: the irrepressible life of Countess Bentinck,” 1997). As so often, the German book title does not seem fortunate: “Eine wahre Geschichte,” for example, is simply omitted.

A third group of novels and stories deals with themes after 1945. “De verborgen bron” from 1950 (The Hidden Source, no German translation) and “De ingewijden” 1957 (The Initiates, 1961) belong together. In the first work, the main character tries to find out more about the life of his own mother, who committed suicide or disappeared long ago. In The Initiates, we learn that she apparently lives in Crete. Six narrators tell of seemingly separate events until it becomes clear that all of their stories are part of one. Incidentally, the last of the narrators, a German soldier gone mad, is the only - indirect - reference to World War II in Haasse's work. In Dutch literary studies, these books belong to the psychological or idea novels, as do “Huurders en onderhuurders” in 1971 (The Tenement, 2001), “Berichten van het blauwe huis” in 1986 (The Blue House, 1998) and “De wegen der verbeelding” in 1983 (The Little Garden, 1999).

Hella Haasse's writing style is always clear and unsentimental, she likes to play with historical and literary allusions and leaves no doubt about her feminist basic attitude, although without militant elements. In “Een gevaarlijke verhouding, of Daal-en-Bergse brieven” 1976 (no German translation) she tries to rehabilitate the Marquise de Merteuil from Pierre Choderlos de Laclos' “Les liaisons dangereuses”, where she is portrayed as decadent and wicked, in a fictional correspondence. One of the means she most often uses to do this is to problematize the male gaze on women. She avoids programmatic statements and preconceived opinions. In an obituary of Hella Haasse, her style of writing is described as “The style of detour”.[V.] It is striking that, despite her precise knowledge of life in Indonesia, she does not say a word about the purely matrilineal and matriarchal Minankabau culture of South Sumatra, which was still unbroken in her youth, or about the fact that in large parts of Java in her time the indigenous population did not enter into marriages in the European sense, but partnerships for a limited period. Offspring born from these partnerships belonged to the women and were brought up in communally run children's homes. Both phenomena were only destroyed by the monotheistic religions from the Middle East, which were becoming more and more prevalent. It is also striking that the bibliographical study of Hella brings to light almost no light-heartedly cheerful scenes. However, she was never considered humorless.

Hella Haasse's writing style is always clear and unsentimental, she likes to play with historical and literary allusions and leaves no doubt about her feminist basic attitude, although without militant elements. In “Een gevaarlijke verhouding, of Daal-en-Bergse brieven” 1976 (no German translation) she tries to rehabilitate the Marquise de Merteuil from Pierre Choderlos de Laclos' “Les liaisons dangereuses”, where she is portrayed as decadent and wicked, in a fictional correspondence. One of the means she most often uses to do this is to problematize the male gaze on women. She avoids programmatic statements and preconceived opinions. In an obituary of Hella Haasse, her style of writing is described as “The style of detour”.[V.] It is striking that, despite her precise knowledge of life in Indonesia, she does not say a word about the purely matrilineal and matriarchal Minankabau culture of South Sumatra, which was still unbroken in her youth, or about the fact that in large parts of Java in her time the indigenous population did not enter into marriages in the European sense, but partnerships for a limited period. Offspring born from these partnerships belonged to the women and were brought up in communally run children's homes. Both phenomena were only destroyed by the monotheistic religions from the Middle East, which were becoming more and more prevalent. It is also striking that the bibliographical study of Hella brings to light almost no light-heartedly cheerful scenes. However, she was never considered humorless.

Haasse was a brilliant speaker. Even at an advanced age, she could extemporize twenty-minute lectures without once appearing unconceptualized.[VI] She did not participate in the hype of the mass media, despite great fame. Almost all of her works reached double-digit print runs, including “De ingewijden” with over fifty. Three of her novels served as models for film adaptations, and she received a large number of awards and prizes, including the Audience Award several times, all the Dutch literary prizes from 1961 to 2004, and two honorary doctorates, in addition to being made an officer and, seven years later, Commander of the French Order of Arts and Letters and Officer of the Legion of Honor. Her works have been translated into 13 languages and are among the most widely read Dutch titles in the German-speaking world.

There is no star-studded Walk of Fame for literary figures, but since July 2007 the planetoid 10250 has been named Hellahaasse.

(Text from 2018; translated with DeepL translation software, edited by Luise F. Pusch Sept. 2021)

For additional information please consult the German version.

Author: Hans Reiners

Literature & Sources

Truijens, Aleid. 2022. Leven in de verbeelding, Hella S. Haasse 1918–2011. Amsterdam. ISBN 978 90214 3638 8/ NUR 320

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.