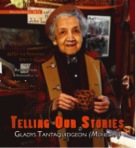

Biographies Gladys Tantaquidgeon

(Dr. Gladys Iola Tantaquidgeon)

born June 15, 1899 in Mohegan Hill, Uncasville, Connecticut, USA

died November 1, 2005 in Mohegan Hill, Uncasville, Connecticut, USA

American Indian (Mohegan) anthropologist, medicine woman, tradition bearer

125th Birthday on 15 June 2024

Biography • Literature & Sources

Biography

“Remember to take the best of what the white man has to offer…and use it to still be an Indian.” This quote was a favorite of Mohegan Indian Gladys Tantaquidgeon, who has been described as “an archetype of Mohegan culture.” She died at the age of 106 after a lifetime of dedication to preserving the culture of her tribespeople and of Indian people generally, even though during much of her life the prevailing view was that Indians should abandon their culture and assimilate to the ways of white people.

Gladys was born on Mohegan Hill, a few miles north of New London, Connecticut on the Thames (formerly called the Pequot) River. The Mohegans were at one time part of the powerful Pequot tribe, an Algonquian-speaking tribe that was based on the eastern side of the river and controlled much of southern New England. But in the early 1600s, due to a dispute between two Pequot leaders—sachem (chief) Sassacus, and sagamore (subchief) Uncas, of whom Gladys was a descendant—a group under Uncas split from the rest of the Pequots and established themselves on the western side of the river, taking the name Mohegan. Sassacus chose to fight against the ever-increasing influx of (primarily English) colonists, whereas Uncas befriended the colonists as the best way to keep his people safe. The animosity between the two Indian groups led the Mohegans to side with the English against the Pequots in the devastating Pequot War in 1637 - 1638, after which the power of the Pequots was virtually eradicated. Forty years later the Mohegans’ mostly positive relationship with the English helped keep the tribe relatively safe during King Philip’s War. Uncas received much criticism for his policy, but unlike many New England tribes, the Mohegans have endured.

Even at a very early age, Gladys showed promise as a future herbalist and culture bearer, often accompanying three Mohegan women elders into the fields to gather plants and learning how to prepare them for healing and spiritual purposes. One of these women—whom Gladys called her nanus or grandmothers—was in fact her maternal grandmother Lydia Fielding. Together with Gladys’s great aunt Fidelia Fielding, the last living speaker of the Mohegan-Pequot language, they imbued Gladys with a strong sense of the importance of carrying forward traditional Mohegan practices in herbal medicine, handicrafts, story-telling, and spiritual observance. They effectively chose Gladys to continue a long line of Mohegan women faithkeepers who for centuries had worked to maintain the Mohegans’ identity in the face of encroachment by often hostile, land-hungry colonists. (The nanus did not teach Gladys much of her native language, however, as they feared she would be punished for speaking it, as they had been when young.)

Recalling some of the nanus' customs around gathering healing plants, Gladys wrote:

While the medicinal properties of many of the plants were quite generally known, there were, it is said, certain of the old women who were more adept in the art of preparing and administering the medicines….The cures were regarded to be, to a certain extent, secret property. The women went out at odd times to places where desired roots and plants grew, when others would not know of their whereabouts….The teachings of those women have been handed down to posterity through individuals considered by them worthy of the right to minister to their kindred.

In connection with the preparation of roots and herbs to be used for medicinal purposes, there are certain rules which must be observed in order to preserve the potent properties of the plants and to cause the remedy to effect a cure. The plants must not be gathered during “dog days,” but just prior to that period. It is believed that the sun is a great healer and strengthener, therefore plants and herbs to be used for medicine should be dried in the sun. [Simmons p. 101]

Sometimes [the women] gathered as many as ten different plants to effect a single cure. They taught me…never to pick more than you need….In the spring, early plants were referred to as weeds, and they were gathered and cooked as weeds—a spring tonic: dandelion, poke, milkweed, plantain, and dock, to name a few. Other plants were more important as sources of healing ingredients, such as bloodroot, boneset, motherwort, ginseng….Some plants are actually poisonous when green. They are dried, ground with a stone or wooden mortar, and gathered. [Fawcett 2000, p. 39]

In other ways, too, Gladys’s early childhood experiences shaped her sensitivity to and reverence for all aspects of nature and the importance of giving thanks for life’s blessings. She learned the Mohegans’ traditional symbols and designs and became adept at stitching and beading them on ceremonial clothing. She accepted tribal beliefs (dismissed by some as superstitions) about such figures as the “Little People” (Makiawisug) who watched over Mohegan Hill, their leader Granny Squannit, and Granny’s husband the giant Moshup, and joined in making offerings to them. Gladys attended a non-Indian school only briefly, and never went to high school. She later remarked, “My maternal grandmother taught me most of what I learned. I don’t recall if I had any books or not.” [Fawcett 2000, p. 14]

When Gladys was only five, the eminent anthropologist Frank Speck from the University of Pennsylvania, whose family were friends of Fidelia Fielding and who had visited and stayed with her in earlier years, returned to the Mohegan tribe to do ethnographic research. Impressed with Gladys’s intelligence and ability, he urged her to “hurry up and grow up little girl, and when I get married I’ll come back with my wife and take you away.” [quoted in Fawcett 2000, p. 64] And he did. Starting when she was ten, Gladys accompanied the Specks on research trips and visited them at their summer home in Cape Ann in Massachusetts; when she was nineteen, Speck invited her to go with him to Penn to work as his assistant and to study anthropology.

When Gladys was only five, the eminent anthropologist Frank Speck from the University of Pennsylvania, whose family were friends of Fidelia Fielding and who had visited and stayed with her in earlier years, returned to the Mohegan tribe to do ethnographic research. Impressed with Gladys’s intelligence and ability, he urged her to “hurry up and grow up little girl, and when I get married I’ll come back with my wife and take you away.” [quoted in Fawcett 2000, p. 64] And he did. Starting when she was ten, Gladys accompanied the Specks on research trips and visited them at their summer home in Cape Ann in Massachusetts; when she was nineteen, Speck invited her to go with him to Penn to work as his assistant and to study anthropology.

While she was at Penn, Gladys encountered Indians from many other tribes. One was a woman from the Penobscot tribe in Maine, Molly Dellis Nelson—like Gladys a protegée of Speck—who later became well known as a dramatic performer and dancer (under the name Molly Spotted Elk), one of many Indians at the time who were able to make a living as entertainers. Often low on cash, occasionally the two would put on shows together, with Molly dancing and Gladys speaking about Indian culture. In the 20s and 30s Gladys did field research among other Algonquian-speaking tribes such as the Gay Head and Mashpee Wampanoag tribes in Massachusetts, the Nanticoke in Virginia, the Cayuga on Ontario, and the Naskapi in Quebec, thus broadening her knowledge of Indian lifeways and in particular, Indian herbal medicine.

Among the Indians from other tribes with whom Gladys worked while at Penn was Witaponoxwe, a medicine man from the Delaware, or Lenni-Lenape tribe, which was anciently related to the Mohegans. Comparing notes with him, she discovered many similarities in the stories, beliefs, and customs of the two tribes, including herbal healing practices. On the basis of this work, in 1942 she published A Study of Delaware Indian Medicine Practice and Folk Beliefs. Thirty years later, she combined this work with a study of Mohegan folk and medical beliefs and practices in Folk Medicine of the Delaware and Related Algonkian Indians.

Gladys received many gifts from the various tribes she visited, such as snowshoes and painted animal skin (parfleche) clothing given to her by the Montagnai Naskapi people, and a Penobscot birch bark canoe. In 1931, with her brother Harold and their father John, she founded the Tantaquidgeon Indian Museum to display these items as well as many that were created and given by Mohegan people, including baskets and other woodwork made by her father. The museum had great significance for Mohegans for a number of reasons. Previously, in the early nineteenth century, the threat of removal hung over the tribe. The US government wanted to move the “uncivilized” and “unchristianized” Mohegans from their lands, as it did the Cherokees and other southern tribes, who were forced to march on the Trail of Tears to settle in Oklahoma. To guard against this, Mohegans—especially women—fought to build a church. Melissa Jayne Fawcett, tribal historian and Gladys’s great-niece, explains in her book Medicine Trail, “Its purpose was to prevent Mohegans from being relocated, for by the 1830s, federal law required any unschooled or nonchurchgoing Indians to go West.” [Fawcett 2000, p. 12] Elsewhere she notes, “Mohegans resisted Federal relocation by claiming to be already ‘civilized’ and ‘christianized.’ To support that claim, the founded a Christian church and school on their reservation in 1831.” [Fawcett 1996, p. 21] The Mohegan Congregational Church became a focal point for the tribe, a place where people could meet socially, work on handicrafts, and discuss tribal politics and other matters.

Now the museum afforded another such setting. It also had an educational purpose. In the following decades, Indian and non-Indian visitors to the museum—the oldest Native American-run museum, still operating today—would learn much about Indian and Mohegan history and lore as Gladys enthusiastically explained the provenance and meaning of each object. As stated in her biography on the Mohegan tribe’s website, “She shared her brother's philosophy that education was the best cure for prejudice. ‘You can't hate someone that you know a lot about.’”

In 1934, the Indian Reorganization Act, a reform effort intended to improve federal policies toward Indians, was set up under the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). On Speck’s recommendation, Gladys headed west, taking a position with the BIA as a community worker at the Yankton Sioux Reservation in South Dakota. There she saw at first hand the hunger, sickness, and death that resulted from a lack of food, clothing, shelter, and medicine, as well as poor education. Two years later she found a way to help the tribe economically: as part of a job with the Federal Indian Arts and Crafts Board, she worked with the Sioux to revitalize their art and sell it. She also taught Indian art and handicrafts on other Indian reservations. Native artistic and sacred ceremonial traditions are often closely intertwined; Gladys played a part in bringing back sacred rituals like the Sun Dance, which the government had forbidden to be performed on reservations. Referring to the Sioux, she later recalled, “In the past, things Indian were rather frowned upon, and every effort was made to try to have these people forget as much of their culture as possible: their language, ceremonies, tribal customs. Part of our work…was to undo that.” [Fawcett 2000, p. 103]

In 1934, the Indian Reorganization Act, a reform effort intended to improve federal policies toward Indians, was set up under the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). On Speck’s recommendation, Gladys headed west, taking a position with the BIA as a community worker at the Yankton Sioux Reservation in South Dakota. There she saw at first hand the hunger, sickness, and death that resulted from a lack of food, clothing, shelter, and medicine, as well as poor education. Two years later she found a way to help the tribe economically: as part of a job with the Federal Indian Arts and Crafts Board, she worked with the Sioux to revitalize their art and sell it. She also taught Indian art and handicrafts on other Indian reservations. Native artistic and sacred ceremonial traditions are often closely intertwined; Gladys played a part in bringing back sacred rituals like the Sun Dance, which the government had forbidden to be performed on reservations. Referring to the Sioux, she later recalled, “In the past, things Indian were rather frowned upon, and every effort was made to try to have these people forget as much of their culture as possible: their language, ceremonies, tribal customs. Part of our work…was to undo that.” [Fawcett 2000, p. 103]

Gladys retired from her travels and returned to Mohegan Hill in 1947. She herself was now a nanu, caring for and playing with nieces and nephews, attending to the sick, advising tribal members about performing ceremonies, and particularly in her role as teacher, meeting with visitors to the museum and educating them about Mohegan history and culture. During the 1950s she worked at a state prison for women in Niantic, observing wryly that having been on an Indian reservation gave her an understanding of the problems women face in difficult circumstances. All the while her reputation as an “archetype of Mohegan culture” was growing. In 1992 she officially became the Mohegan tribe’s Medicine Woman. She received honorary degrees from the University of Connecticut in 1987 and from Yale University in 1994; in 1996 she received the Harriet Tubman award from the National Organization for Women for “consistent endeavor in the area of social justice.” She was also honored by the Connecticut Education Association’s Friend of Education Award, and was elected to the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame.

In 1978 the Mohegans began to seek federal recognition for their tribe—a daunting challenge, as the government required proof that the tribe had existed continuously since historic times. At first they were turned down for lack of sufficient proof, but they finally succeeded in 1994, a victory due in large part to the fact that over the years Gladys had carefully kept many tribal documents—tribal rolls, records of births, graduations, marriages, and deaths, and extensive correspondence with tribal members—and stored them in Tupperware containers under her bed. With the help of her sister Ruth, she organized the documents to make the tribe’s case. The Mohegans’ sovereign status qualified them for federal funds and enabled them to build their highly successful Mohegan Sun casino and luxurious hotel.

Gladys never married; perhaps, living such a full life, she didn’t have time. Speaking of her teenage years, she noted, “There were certain boys in the community. But I always had too many other things going on.” [Fawcett 2000, p. 19] However, when the Mohegans held a big celebration for her 100th birthday on June 15, 1999, her eight-year-old grand-nephew David Uncas Sayet spoke eloquently: “You were chosen by the Creator, which was a very good choice of a medicine woman… I hope you live forever so you can keep continuing your journey, and we will keep giving you our respect. I hope you have a great one hundredth birthday. Thank you for giving us care.” [Fawcett 2000, p. 155] There were many other outpourings of appreciation and gratitude that day for all Gladys had done for the tribe, and the governor of Connecticut declared the day “Gladys Tantaquidgeon Day.” Melissa Jayne Fawcett has observed,

Gladys never married; perhaps, living such a full life, she didn’t have time. Speaking of her teenage years, she noted, “There were certain boys in the community. But I always had too many other things going on.” [Fawcett 2000, p. 19] However, when the Mohegans held a big celebration for her 100th birthday on June 15, 1999, her eight-year-old grand-nephew David Uncas Sayet spoke eloquently: “You were chosen by the Creator, which was a very good choice of a medicine woman… I hope you live forever so you can keep continuing your journey, and we will keep giving you our respect. I hope you have a great one hundredth birthday. Thank you for giving us care.” [Fawcett 2000, p. 155] There were many other outpourings of appreciation and gratitude that day for all Gladys had done for the tribe, and the governor of Connecticut declared the day “Gladys Tantaquidgeon Day.” Melissa Jayne Fawcett has observed,

“Gladys, probably more than anyone else that I can think of, is the epitome of having spent a lifetime working for social justice. Throughout the century that has been her focus, whether it was for her own people or other Indians out west or even with the general public. She has made people aware of forgotten groups of people.” [“Mohegan Medicine Woman Honored for Life’s Work”]

Fawcett also stated, “Much credit for tribal survival is due to Uncas’s decisions and those of the chiefs and tribespeople after him who followed his example.” [Fawcett 2000, p. xiii] Foremost among those tribespeople was Gladys Tantaquidgeon.

Author: Dorian Brooks

Literature & Sources

Fawcett, Melissa Jayne. Medicine Trail: the Life and Lessons of Gladys Tantaquidgeon (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 2000)

Fawcett, Melissa Jayne.The Lasting of the Mohegans: Part 1, the Wolf People (Ledyard, CT: Pequot Printing, 1996)

Gladys Tantaquidgeon biography

Gladys Tantaquidgeon Obituary, New York Times, November 2, 2005

McBride, Bunny. Molly Spotted Elk: a Penobscot in Paris (Norman and London: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995)

“Mohegan Medicine Woman Honored for Life’s Work,“ The Day, March 1, 1995

The Mohegan Tribe official website

Oberg, Michael Leroy. Native America: a History (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010)

Oberg, Michael Leroy. Uncas, First of the Mohegans (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2003)

“Running Against Time: Mohegan Woman Preserves Mohegan Culture” (PENN Arts & Sciences, School of Anthropology Alumni Newsletter, Summer 2001)

Simmons, William S. Spirit of the New England Tribes: Indian History and Folklore, 1620 – 1984 (Hanover and London: University Press of New England, 1986)

Tantaquidgeon, Gladys. Folk Medicine of the Delaware and Related Algonkian Indians (Harrisburg, PA: The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Anthropological Series no. 3, 1995)

Image Sources: Penn Arts and Sciences, Summer 2001 http://www.sas.upenn.edu/sasalum/newsltr/summer2001/running.html

Quinnetukut Magazine, Winter/Spring 2012 http://www.iaismuseum.org/magazine.shtml

The Mohegan Tribe website http://www.mohegan.nsn.us/Heritage/gt_makiawisug.aspx

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.