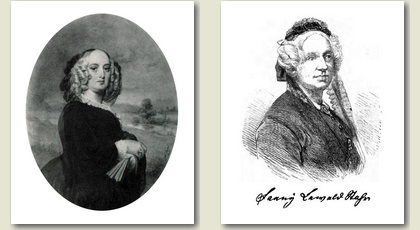

(Fanny Mathilde Auguste Marcus [Name vor Umbenennung]; Fanny Stahr [Ehename]; Fanni Lewald Stahr; Iduna Gräfin H. H. [Pseudonym]; Adriana [Pseudonym])

born 24 March 1811 in Königsberg

died 5 August 1889 in Dresden

German writer

125. anniversary of death day on 5 August 2014

Biography • Quotes • Weblinks • Literature & Sources

Biography

She always thought it fortunate to be born the first child of David and Zipora Marcus and to be raised in the city of Kant. Her “entlightened” father nevertheless expected obedience. He dictates her reading, represses her desire to know, and teaches self-censorship. Religious discussion is forbidden; Fanny learns from a neighbor that she is Jewish. Her father chooses the family name Lewald to disguise their origins. He breaks up her first romance and determines when she must convert to Protestrantism, a nominal conversion she regrets. She accompanies her father on a business trip in 1832, ostensibly to widen her horizon, but in fact he is seeking a suitable husband. More important is his earlier decision to send Fanny to a co-ed Pietist school with her brothers, for this fires her ambition. At age 13 she must stay home once more and be trained for a housewifely role. She begins to see family love as a kind of tyranny. It takes years though for her to emancipate herself. The first step—she refuses to marry a man chosen by her parents.

In her autobiography Meine Lebensgeschichte (1862) Lewald stilizes her development as a novel of education in three stages. She discovers her writing talent by chance, and her early works appear anonymously as the family wishes. Her mother does not live to witness the success of her first three novels—Clementine, Jenny, Eine Lebensfrage—in the 1840s. Lewald can move into an apartment of her own in Berlin and support herself. She need not be forced into a loveless marriage. Rahel Varnhagen’s letters and women friends in Berlin and Rome provide models of independence. In 1846 she falls in love with Adolf Stahr, a teacher an philologist. Soon thereafter her beloved father dies. She takes on the support of two younger sisters and commits herself to her profession, giving up anonymity. Unable to renounce her love for a married man, she treats the liaison openly. The lovers marry in 1855 after Stahr is finally able to divorce, but she makes sure she will control her own finances. As a “female author” she retains the name Lewald.

The 1848-revolution she experiences in Paris and Berlin, and in1850 she travels to England and Scotland. Travel literature becomes a mainstay of her oeuvre. After 1852 Stahr lives with Lewald in Berlin where she maintains a salon. Daily life with the sickly Stahr and raising his two adolescent sons brings joy and sorrows. These decades are her most productive, however, as Stahr supports her ambition. She abandons tendentious novels and fantastic tales in favor of realistic works, subscribing to a vision of an androgynous human wholeness to which each person can strive. In her fiction the most admirable figures are the ones cabale of transformation.

In addition to the major novels—Wandlungen (1853), Von Geschlecht zu Geschlecht (1864-66)—and collections of tales, Lewald publishes essays on the the rights of women—Osterbriefe für die Frauen (1863) and Für und wider die Frauen (1870). She argues for their right to education and self-fulfilling work outside the home. She also envisions marriage as a partnership of equals. Lewald does not think that German women are ready for the franchise as they first need to be educated. Women should go to the same high schools and universities as men. She appeals to her mainly middle-class readership to extend sisterly solidarity to working-class women, and she promotes any innovation that might make housework less onerous, e.g. communal kitchens.

Lewald’s voice was progressive but not radical, and after 1870 she became more conservative, but she continued to demand equality for women in education. After Stahr’s death leaves her adrift in 1876 she seeks renewal in Rome. True to her motto, she does not tire. She publishes novels including the thousand-page Prussian saga Die Familie Darner (1887). She prepares her legacy including a diary of aphorisms, Gefühltes und Gedachtes (1900), and she continues to travel. Four days after her death in Dresden Lewald is buried next to Stahr in Wiesbaden. She is remembered by the next generation in different ways, celebrated on the one hand by some admiring men as a “Prussian female patriarch,” but by younger women with equal justice as a “co-sister” and “path-breaker.”

For additional information please consult the German version.

Author: Margaret E. Ward

Quotes

Quotes by Lewald, transl. by Margaret E. Ward And so I reiterate again and again the demand for women’s emancipation, an emancipation to serious fulfillment of duty and serious responsibility and therefore to equality of opportunity and equal standing in society, which every indivudal who wants to be do serious work among like-minded people must seek to acquire.

I always argued that we should instruct and educate women in a manner that will enable them to provide for themselves completely. This will protect them against the undignified necessity to marry without inclination, in other words— in order not to mince words—to sell themselves for the price of being provided for their whole lifelong.

Everything that people usually propose as counter arguments to the independence of women is both false and a self-deception—the comments about the “El Dorado” of family life that is also supposedly the exclusive vocation for girls, or the imagined dangers that could accrue to women who are out in the work place earning money.

The main thing is to think through times and things, people and their works in order to do them justice through understanding.

One has to first be someone, in order to give something up, one has to have possessed oneself in order to be able to give oneself to another.

If I am to be a writer, I have to be able to say what I think, and to touch on any topic that appears relevant to me. I cannot take any heed of what you might want to hear from me, or what you think it appropriate for the children (as he still referred to all of us) to hear. ... I will not be able to live the way I have up to now forever. If I can earn enough money to do so, I have to see the world and interact more freely with people—with men who can further my career—than it is possible to do here at home around the tea table in the presence of my parents and five sisters.

Links

http://www.zeno.org/Literatur/M/Lewald,+Fanny

Literature & Sources

Lewald, Fanny. 1988-89 [1861-62]. Meine Lebensgeschichte. Hg. Ulrike Helmer. Neuaufl. d. 3-bändigen Originalaufl. Bd. I: Im Vaterhause. Bd. II: Leidensjahre. Bd. III: Befreiung und Wanderleben. 3 Bde. Frankfurt/M. Helmer.

Lewald, Fanny. 1989. Politische Schriften für und wider die Frauen. Hg. Ulrike Helmer. Frankfurt/M. Helmer.

Lewis, Hanna Ballin. 1992. The Education of Fanny Lewald: An Autobiography. Trans., intro., annotated, and abridged. Albany. State U of New York Press.

Ornam, Vanessa van. 2002. Fanny Lewald and Nineteenth-Century Constructions of Femininity. North American Studies in Nineteenth-Century German Literature 29. New York. Peter Lang.

Rogols-Siegel, Linda. 1988. Trans. Fanny Lewald’s Prince Louis Ferdinand. Studies in German Thought and History 6. Lewiston, N.Y. Mellen.

Ward, Margaret E. 2006. Fanny Lewald: Between Rebellion and Renunciation. Studies on Themes and Motifs in Literature 85. New York. Peter Lang.

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.