born on May 11, 1907 in Pirna

died on July 15, 1976 in Dresden

German painter and resistance fighter

115th birthday on May 11, 2022

Biography • Literature & Sources

Biography

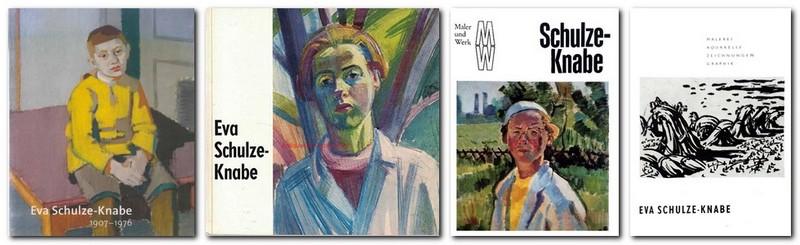

Eva Schulze-Knabe was one of the most important artists of the GDR. She is regarded as a “state-supporting commissioned artist whose past as a resistance fighter against the Nazi dictatorship fitted ideally into the official historical picture”, and who today has been unjustly forgotten, as her daughter and granddaughter sum up. In 1984, a street in Dresden was named after her.

Eva Schulze-Knabe studied in Leipzig and at the Dresden Art Academy, joined the artists' group ASSO and in 1931 the Communist Party of Germany. In the same year she married the like-minded artist Fritz Schulze. Both were friends with Hans and Lea Grundig and the writer Auguste Lazar, among others.

After the beginning of fascist regime, they tried to maintain the structures of the illegal KPD with some comrades. In August 1933 they were arrested for the first time, imprisoned for half a year, but acquitted at the trial.

After the beginning of fascist regime, they tried to maintain the structures of the illegal KPD with some comrades. In August 1933 they were arrested for the first time, imprisoned for half a year, but acquitted at the trial.

They again formed a small resistance circle. In 1941, the group was exposed, and Fritz Schulze and his two comrades were sentenced to death by the ” People's Court” in 1942 and executed in Plötzensee. Eva Schulze-Knabe received a life sentence in a penitentiary.

After her liberation in 1945, she lived in Dresden as a freelance artist and used her artistic skills to help build the new social order in the GDR. She received many awards, including the Medal of Merit, twice the Fatherland Order of Merit and finally in 1969 the National Award of the GDR.

She had been exposed to various influences during her studies - from Expressionism to Cubism to New Objectivity - without joining any one current. Early on, she created frontal portraits of self-confident people, such as “Hilde Ulbricht” (around 1933) and “Laundry Paul” (charcoal, 1934) or the “Portrait of a Negro” (1931) with clear, compact forms. The colors are muted, occasionally glaring, as in “Junge im gelben Pullover” (Boy in a Yellow Sweater, 1931). In small-format linocuts, similar in design to those of Frans Masereel, she focused on the poverty and misery of the Weimar Republic. Her life-size self-portrait of 1931, for which she received a prize in the same year, is reminiscent in expression of wo rks by the Soviet avant-garde of the 1920s. She stands defiantly proud, with a simple smock dress and combed-back hair in front of the viewer, her right leg out in front of her, her left hand on her hip. Also fascinating is her large double portrait with Fritz Schulze on brown-red paper (charcoal, heightened with white) from 1934. She fought for complete equality for women, as a comrade testified to the Gestapo.

rks by the Soviet avant-garde of the 1920s. She stands defiantly proud, with a simple smock dress and combed-back hair in front of the viewer, her right leg out in front of her, her left hand on her hip. Also fascinating is her large double portrait with Fritz Schulze on brown-red paper (charcoal, heightened with white) from 1934. She fought for complete equality for women, as a comrade testified to the Gestapo.

While in prison, she drew herself on envelopes, with sharp lines, disfigured by illness, hunger, and fear. She later processed the horrors of fascist persecution in pastels of the “People's Court,” which were unusual for her.

Her impressions of destroyed Dresden also bear witness to how she tried to shape the nightmarish in new ways. Her most convincing portraits from the GDR era include that of the “Worker's Wife” (“my caretaker”) from 1955 and that of the “Hero of Labor Karl Krüger” (1957), but also that of the young hopeful “Party Secretary Nacke” (1961) and that of the weaver and Volkskammer deputy Elsa Hentschke (1962). Beguiling is the picture of the daughter (“Tina in a striped sweater”, 1966) and touchingly sensitive that of a reading African student, which was acquired by the Dresden Picture Gallery. The people portrayed mostly appear serious, introverted, even closed off - one will look in vain for the famous “laughing brigadier” of Socialist Realism in her work.

In expressionist form and color, she repeatedly painted the landscape of her Saxon homeland, where she had so enjoyed hiking or biking as a young woman.

In 1971, she created her unheard-of “Self-Portrait with Helmet,” which shows her in a miner's outfit and glasses, gaunt, determined, with her right hand on her hip and a brush in her left hand - without any “feminine beauty”. It was the only GDR artwork to be included in the monograph “How Women See Themselves” by the English art historian Frances Borzello, published a few years ago. The way she portrayed herself must have been the way she was - a strong, independent and strong-willed woman who was on her own for most of her life.

In 1971, she created her unheard-of “Self-Portrait with Helmet,” which shows her in a miner's outfit and glasses, gaunt, determined, with her right hand on her hip and a brush in her left hand - without any “feminine beauty”. It was the only GDR artwork to be included in the monograph “How Women See Themselves” by the English art historian Frances Borzello, published a few years ago. The way she portrayed herself must have been the way she was - a strong, independent and strong-willed woman who was on her own for most of her life.

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version), edited by Almut Nitzsche, May 2022. – For additional information please consult the German version.

Author: Cristina Fischer

Literature & Sources

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.