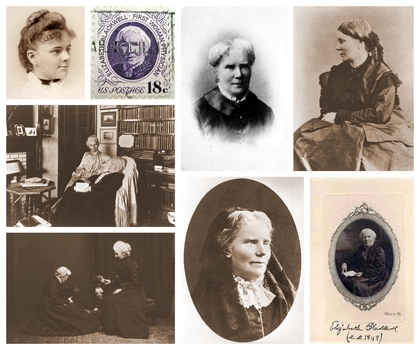

Biographies Elizabeth Blackwell

(Elizabeth Blackwell, M.D.)

born 3 February 1821 in Counterslip near Bristol

died 31 May 1910 in Kilmun, Scotland

First American woman doctor; pioneer of preventive medicine

105th anniversary of death on 31 May 2015

Biography

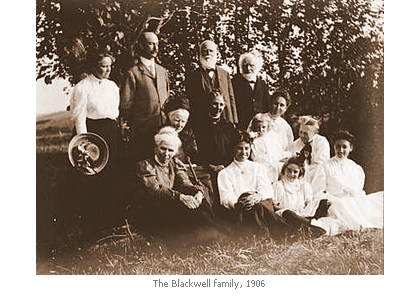

Elizabeth Blackwell was born to Hannah Lane and Samuel Blackwell on February 3, 1821, near Bristol England. A sugar refiner by trade, Samuel also served as a lay preacher for the “Independent” church. Hannah surrounded her family with the music and books she valued from her childhood. In addition to being disciplined in the home by Samuel's four unmarried sisters, Elizabeth and her sisters studied with private tutors, learning the same subjects as their brothers. The Blackwell children grew up surrounded by a progressive social consciousness, including support for women's rights, temperance and the abolition of slavery. Partly as a result of this upbringing, many of the nine Blackwell children led pioneering professional lives: Anna became a newspaper correspondent, Elizabeth and Emily, physicians, Ellen, an author and artist, and Samuel and Henry, reformers, one marrying Antoinette Brown, the first American woman minister, and the other wedding abolitionist and feminist Lucy Stone.

Because of the loss of Samuel's sugar refinery in 1832, the Blackwells moved to the United States, where the family had more success at abolitionist and cultural activities than material prosperity: William Lloyd Garrison became a close family friend during their time in New York City, but when Samuel Sr. died after the Blackwells moved to Cincinnati in 1838, the family was quite poor. After helping her mother and two older sisters run a private school for four years, Elizabeth “determined to seek a career in medicine and thus place a 'strong barrier' between herself and matrimony” (Notable American Women 162).

Although Yale, Harvard, and every medical school in Philadelphia refused admittance to Blackwell because of her gender, she graduated from New York's Geneva College in January, 1849, becoming the first woman doctor in the United States. Between July 1849 and August 1851, Elizabeth sought practical experience in Europe, where she attracted several supporters, including the Herschels and Florence Nightingale. Although she later trained successfully in England under Dr. James Paget, in Paris she was dismayed to find that the only position open to a woman was that of student midwife.

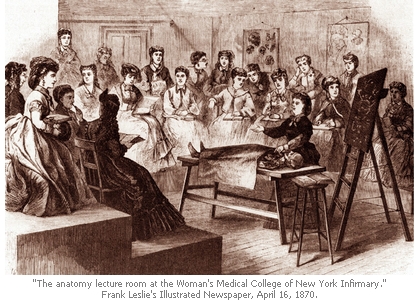

In 1851, Blackwell returned to New York, where she bought a house to use for an office, as no one would rent space to a woman doctor. By 1854, she had delivered and published a series of lectures on good hygiene, entitled The Laws of Life, with Special Reference to the Physical Education of Girls, attracted some loyal Quaker patients, and, to ease her loneliness, adopted a seven-year-old orphan named Katharine Barry. In 1857, Dr. Marie Zakrzewska and Dr. Emily Blackwell helped Elizabeth expand the one-room dispensary she had established in a poor city neighborhood, founding the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. A year later, Elizabeth founded the Woman's Medical College of the NY Infirmary, establishing rigorous entrance and exit examinations to prepare students for the scrutiny they would receive as women in the medical profession. In addition to contributing to such institutional support for female physicians, Blackwell later served as personal mentor to Elizabeth Garrett and Sophia Jex-Blake, both of whom went on to become pioneering doctors in Britain. During the American Civil War, Blackwell helped found the Woman's Central Association for Relief, which helped supervise medical care given to soldiers, and impacted federal policy by (successfully) urging the Department of War to establish the U.S. Sanitary Commission in 1861.

In 1869, Elizabeth and Kitty Barry had returned to England, exactly ten years after Blackwell had been the first woman included in the British Medical Register. Two years later, Elizabeth and like-minded health professionals founded the National Health Society, which espoused Blackwell's motto, “prevention is better than cure” (NAW 164). Blackwell chaired the gynecology department at the New Hospital and London School of Medicine for Women during 1875, but suffering from biliary colic, soon retired with Kitty to an ocean-front home in Hastings.

Before her death in 1910, Elizabeth lectured and published works on moral and socio-economic reform, including Counsel to Parents on the Moral Education of Their Children (1878), Christian Socialism (1882), and The Human Element in Sex (1884). In these works and others, Blackwell criticized the excessive use of surgery in medical practice, combatted economic injustice, and challenged unequal judgment of women's sexual behavior. Although she opposed vaccinations and animal experimentation, and made no direct scientific contribution to medicine, Blackwell was a pioneer in her devotion to preventive medicine, public health and women's advancements in society. Blackwell hesitated to identify directly with the feminist movement of her time, writing, “'I believe that the chief source of the false position of women is the inefficiency of women themselves'” (Forster 55). However, Elizabeth Blackwell's life work demonstrated her belief that “gender [should] not be an obstacle to achievement” (Forster 57).

For additional information please consult the German version.

Author: Sarah K. Horsley

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.