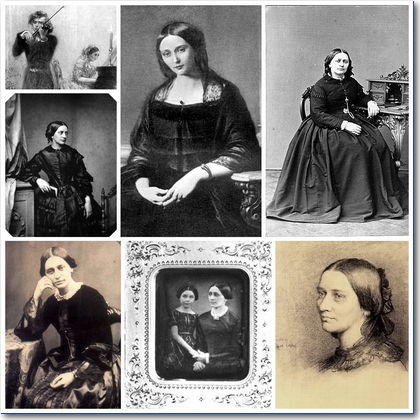

Biographies Clara Schumann, geb. Wieck

(Clara Josephine Schumann, geb. Wieck)

Born 13 September 1819 in Leipzig

Died 20 May 1896 in Frankfurt am Main

German pianist and composer, wife of composer Robert Schumann

200th birthday on 13 September 2019

Biography • Weblinks • Literature & Sources

Biography

Her remarkable early training and discipline, outstanding musical talent, and determined character and sense of mission made Clara Wieck Schumann one of the most widely acclaimed German women of the 19th century. Best known in her time as a consummate performer and tireless promoter of her husband Robert Schumann’s works, as well as a sought-after teacher and composer in her own right, she has remained famous into the 20th century and beyond – memorialized in Germany on postage stamp and currency and the subject of film (e.g. by Helma Sanders-Brahms) and drama (e.g. by Elfriede Jelinek).

From the beginning, her life story has fascinated. As an amazing child prodigy Clara Wieck was praised and fawned over by royalty and the artistic and intellectual elite of the time, from the Austrian emperor to Goethe and the Austrian poet Grillparzer. As a young woman her romance with and marriage to the charismatic and gifted Robert Schumann seemed to offer a unique new model for artistic partnership, as the couple traded musical ideas and shared compositional projects. The preeminence in the marriage of Robert’s work, however, reflected traditional values; although he cherished and relied on Clara’s musical talent and contributions, Robert nonetheless expected his wife to subordinate her creativity to his and to fulfill the roles of managing the home and caring for their seven children. (An eighth child died in infancy.) And Clara was duly celebrated as the devoted wife and mother. Finally, during the 40 years after her husband’s death in 1856 Clara Schumann achieved legendary status as an almost superhuman being, a “priestess” dedicated to her art, her children, and to performing and promoting her husband’s music.

An explosion of new research since the 1980’s, partly stimulated by the women’s movement, has revised the traditional image to reveal a more human struggle for self-assertion and survival amidst competition, personal disappointments, devastating sorrow, and the challenges of managing both family and career. Clara Schumann’s importance as a composer in the “new Romantic” school and as master teacher influencing generations of pianists has also received increased recognition and analysis (especially by Reich, Weissweiler, Klassen).

Clara was the daughter of Marianne Tromlitz Wieck, a talented soprano and pianist, and Friedrich Wieck, an ambitious piano teacher and gifted businessman, owner of a piano rental and parts business in Leipzig. Marianne, a former student of Wieck, contributed to his reputation through her concerts and teaching, but left the domineering, even abusive man when Clara was not quite five. The sensitive child responded to the tensions in the family, including Wieck’s rages, by not speaking until age four, while in the security of her maternal grandparents’ home. Saxon law gave custody of children to the father in cases of divorce, and Wieck reclaimed “his” Clara on her fifth birthday. Determined to capitalize on the then popular fashion of young female piano virtuosi, he set about turning his daughter into a child prodigy. He began a rigorous program of training at the piano which extended to total control of the young girl’s life; instead of attending school – which she did only very briefly – she had a regular routine of hours at the piano, long walks in the outdoors, private lessons in music theory and composition, French and English.

Wieck began a daily diary for his daughter in which he wrote in her name, referring to himself as “Father.” (Clara would be 19 before she gained personal control over her diary.) This seeming assumption of Clara’s personal identity reflects Wieck’s complete dedication to her development as his own life project. Yet such close monitoring also taught Clara practical tips that would prove useful in her adult life about managing concerts and touring, for example. It also made it likely that the girl might absorb some of Wieck’s hypercritical, impatient character. Clara, a responsive and disciplined pupil, worked hard and was grateful for her father’s laser-like atttention, but hardly had a childhood in the traditional sense and missed the love her mother would have given, as she later wrote to Robert Schumann.

Father loved me very much, and I loved him too, but I did not have what a girl needs so much – a mother’s love … and because of that was never really happy. (NR 133)

Wieck’s efforts were richly rewarded by Clara’s stunning success – from her first concert appearance in the Leipzig Gewandhaus at age nine to performances in Dresden and on multiple tours with her father, for example to Paris, Weimar, Vienna, Prague and Berlin. She also began composing; her Opus 1 (“Quatre Polonoises pour le Pianoforte”) was published in 1831. When the charming and gifted piano student Robert Schumann (1810-1856) began living and boarding with the Wieck family in 1830, his and Clara’s mutual interest in composing was one strand in the emotional bond that developed between the two; they traded musical ideas and were inspired by and responded to each other’s compositions. Robert:

In your Romanze I can hear all over again that we must become husband and wife […] Every one of your thoughts comes from my soul, just as I owe all of my music to you. (Schumann, Clara und Robert Schumann. Briefwechsel. Ed Eva Weissweiler. Vol 2, 1839. Critical ed. Basel: Stroemfeld/Roter Stern, 1987. S. 629. Trans. J.H.)

When Wieck learned of the romance between the two he compelled his daughter to break off all contact with the young composer; two years later, in 1837, he vehemently rejected Schumann’s formal request to marry Clara. Wieck feared the loss of his perceived possession and creation, his “golden goose.” Moreover, although he admired Schumann’s gifts he deemed him insufficiently able to support a wife and family. The two were eventually (1839) forced to petition the Court of Appeals to allow them to marry without Wieck’s permission. A year later their appeal was granted despite Wieck’s often outrageous efforts to discredit them both, and the marriage took place on September 12, 1840.

After all, Klara also understands that I have a talent to nurture, and that I’m now at my best and have to take advantage of my youth as long as I have it. That’s the only way it can work in artist-marriages; you can’t have everything together …. (“Ehetagebuch” Oktober 1842, cit. in B 175. Trans. JH)

She had already confided her fears to the diary a year earlier:

My piano playing is falling behind. This always happens when Robert is composing. There is not even one little hour to be found in the whole day for myself! If only I don’t fall too far behind. Score reading has also been given up once again, but I hope it won’t be for long this time…. (“Ehetagebuch” June 2, 1841. Trans NR 88 = Robert Schumann Tagebücher Pt. 2 ed. Gerd Nauhaus. Leipzig: Deutscher Verlag für Musik, 1987,162)

Moreover, to add to her responsibilities, Clara had given birth to a daughter Marie on September 1, 1841, the first of what would be eight children Clara would bear.

Clara’s drive to perform involved accepting invitations to travel to distant cities, something a woman would normally do only together with her husband or in company of a relative or other chaperone. Robert, who had expressed some concern at what people would say if she travelled alone, did accompany her on a few concert tours, but almost always at physical and psychological/emotional cost to him. He was more comfortable in the quiet surroundings of home, where he could work; moreover he had mixed feelings at seeing his wife applauded so publicly, especially before he became well known and celebrated himself. When Clara, by now an experienced concert organizer, did leave him to tour on her own, Robert fell into despondancy and depression. He reluctantly agreed to accompany her on an arduous tour of Russia in 1844 which Clara mastered with bravoura, but during which he endured serious physical and emotional suffering.

It seems that Clara resisted acknowledging the gravity of her husband’s condition until he finally experienced a severe mental and physical breakdown in August 1844. The family, which now included a second daughter, Elise, left the humming musical capital of Leipzig and moved to Dresden, possibly in hopes that a change to the quieter atmosphere would be salutary for Robert. He did in fact compose many of his great works there, but the creative phases were followed by depressions that required his wife to take on more and more responsibility – for family, household and, increasingly, the defense and support of her husband’s career. Moreover, during the five years in Dresden Clara bore four more children and experienced one miscarriage. Despite the fact that her own career took second place during these years, she still was an important source of family income, by giving lessons and through concerts in Dresden, Leipzig, and on tours to Vienna, Prague and Berlin.

In September 1850 the family moved to Düsseldorf, where Robert had been offered the position of music director of the Municipal Orchestra and Chorus. Eventually they settled in an apartment which was spacious enough for Clara, for the first time, to have a room with her own piano where she could practice, even when Robert was composing. A central development of the time in Düsseldorf was the friendship with the young Johannes Brahms, who, still at the beginning of his career, paid a first visit to the admired older composer and his wife in September 1853. Both Schumanns were swept away by Brahms’ personal appeal and the genius of his music. Along with his friend, the violinist Joseph Joachim, Brahms would be among the most important contacts and supports of the Schumann famiily in the difficult months and years ahead. His admiration and love for Clara were certainly returned, and the unique relationship persisted till Clara’s death, although its originally passionate nature gradually resolved into deep friendship.

Soon after Robert Schumann assumed his duties in Düsseldorf it became clear that he was unsuitable for the position; a poor conductor and communicator, he had to rely on his wife for assistance during rehearsals. After mounting dissatisfaction with his performance, the city administrators informed Clara in November 1853 that he would be allowed to conduct only his own works; all other conducting responsibilities would be carried out by the assistant conductor. Robert Schumann’s mental condition had also deteriorated alarmingly in 1852-53; his final breakdown began in 1854, culminating in a suicide attempt on February 27 and his hospitalization at Endenich (near Bonn). He lived on there for two and a half more years with periods of greater and lesser lucidity. Schumann’s doctors did not permit Clara to visit until shortly before his death, presumably out of concern both for their patient’s stability and for Clara’s likely reactions to seeing her husband in such reduced circumstances.

As a mother with a demanding performing career, Clara Schumann conscientiously tried to provide her children with an adequate education, even though it often meant sending them away from home from an early age, to relatives or boarding school – a common practice among middle class families in the 19th century. While she was concerned with their progress and problems, her actions and letters suggest that she was often not as sensitive to their emotional needs as they might have wished.

Clara Schumann died following a series of strokes, forty years after the death of her husband. Her devoted friend Brahms died eleven months later.

Author: Joey Horsley

Links

For additional material and visual images, please see the German version.

Janina Klassen, Artikel „Clara Schumann“, in: MUGI.Musikvermittlung und Genderforschung: Lexikon und multimediale Präsentationen, hg. von Beatrix Borchard und Nina Noeske, Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hamburg, 2003ff. Stand vom 25.4.2018

Clara Schumann, in Schumann Netzwerk.

Clara Schumann, in Diana Ambach, Women of Note, Celebrating 300 Years of Music by women.

Literature & Sources

Borchard, Beatrix. 2015. Clara Schumann: ihr Leben: eine biographische Montage. 3. überarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage. Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag. (= B)

Klassen, Janina. 2009. Clara Schumann: Musik und Öffentlichkeit. Köln: Böhlau.

Reich, Nancy B. 2001 (1985). Clara Schumann, the Artist and the Woman. Revised Edition. Ithaca and London: Cornell UP. (= NR) (Deutsch 1991: Clara Schumann. Romantik als Schicksal. Eine Biographie. Deutsch von Irmgard Andrae. Reinbeck bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, Wunderlich.)

Steegmann, Monica. 2004. Clara Schumann. London: Haus, 2004.

Weissweiler, Eva. 1990. Clara Schumann: Eine Biographie. Hamburg: Hoffman und Campe.

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.