(Elinore Harris [Geburtsname]; Eleanora Fagan [Taufname]; Lady Day [Spitzname]; Eleonora McKay [Ehename])

born on 7 April 1915 in Philadelphia

died on 17 July 1959 in New York City

American Jazz singer

Biography • Quotes • Weblinks • Literature & Sources

Biography

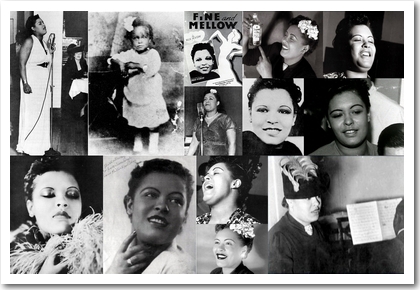

Billie Holiday overcame an impoverished and abusive childhood to become the definitive jazz singer of the 1930’s and 40’s. Although she lacked any formal musical training she had an uncanny ability to “hear” rhythms, syncopations and cadences and developed her own unique improvisational style, influencing the development of jazz and pop music for decades to come with the mesmerizing emotional intensity of her singing. Inspired as a child by recordings of Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith, she eventually sang with virtually all the greats of the Swing era: Count Basie, Artie Shaw, Art Tatum, Teddy Williams and Benny Goodman among many others. Frank Sinatra listed Holiday as his most important influence.

Almost as famous for her life-story as for her music, Billie became a legend in her own time for her role as the “tragic” victim of male abuse, racism, drugs and alcohol, and she appropriated this role for the narrative ballads she chose in the later years of her career, such as “Ain’t Nobody’s Business If I Do.” Her earlier repertoire had also included livelier songs and blues rhythms, but even early on she emphasized the slow torch song, the lament of a woman unlucky in love, such as “Lover Man.” The popular legend of the self-destructive artist, however, represented only a partial aspect of Holiday’s reality. From her earliest days as a singer she gave as good as she got, loved to live it up and enjoyed the life of a Harlem nightclub performer, complete with marijuana, alcohol, and sex (with both men and women). Nightclub owner Barney Josephson characterized her unique personality:

Billie Holiday … did what she liked. If a man she liked came up, she’d go with him; if a woman, the same thing. If she was handed a drink, she’d drink it. If you had a stick of pot, she’d take a cab ride on her break and smoke it. If you had something stronger, she’d use that. …. She didn’t apologize for it and she didn’t feel ashamed. All she wanted was to have fun in whatever way it struck her. She was sensitive, she was proud…. She had a real zest for life. As a performer, she could make you fall in love, she could break your heart.… There was no other person on the face of this earth who was like her. Billie Holiday was a single edition. (Josephson quoted in Nicholson 118)

The source of much of the mythology of her life, Holiday’s “autobiography” Lady Sings the Blues (1954), was ghost-written by New York Post writer William Dufty and is unreliable in many details, and the film of the same name (starring Diana Ross as Billie, 1972) is even less accurate.

Born in Philadelphia to the 19-year-old single domestic worker Sarah (Sadie) Harris (later Fagan and Gough), Elinore Harris (Eleonora Fagan) endured a difficult childhood in Baltimore. Her mother told her that the talented guitarist and banjo player Clarence Holiday was her father. Since Sadie often worked as a maid to white women travelers to earn a living, Eleanora was shunted among relatives and friends. She was twice committed to a Catholic reformatory, the House of Good Shepherd for Colored Girls, once for truancy and again at age 11 after she had been raped by a neighbor. Eleanora dropped out of school in the fifth grade, but had discovered the music of Louis Armstrong, or Pops, as she called him, when she heard it played on a Victrola in a neighborhood brothel.

In 1929 she followed her mother to Harlem, where both were soon arrested in a vice raid and charged with prostitution; Eleanora spent a short time in a workhouse and then, at age 14, began singing for tips in Harlem nightclubs. She adopted her father’s surname and took the name Billie after Billie Dove, her favorite actress on the silent screen.

In 1933 she was “discovered” by the young record producer John Hammond (who also recorded Bessie Smith and fostered the careers of many artists, among them Benny Goodman, Count Basie, Teddy Wilson, Pete Seeger and later Aretha Franklin, Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen). When he heard Billie Holiday singing at Covan’s night club he was amazed; as he later recalled, “The way she sang around a melody, her uncanny harmonic sense and her sense of lyric content was almost unbelievable in a girl of seventeen” (as quoted in Nicholson 39). Hammond arranged her first recording session with Benny Goodman and in 1935 signed her to Brunswick Records to record with pianist Teddy Wilson for the growing jukebox trade. The recordings with Wilson are among her finest; by now she had already established her revolutionary style as a jazz singer who improvises rhythm and melody to achieve compelling expression. During this time she also met the brilliant tenor saxophonist Lester Young, who became a close friend and musical collaborator. For a time he lived with Billie and her mother. He gave her the name “Lady Day,” and she called him “Prez,” for president. They recorded together for Columbia Records until early 1941, leaving “one of the most important recorded legacies in the history not only of jazz, but also of twentieth-century music” (Nicholson 85).

In late 1937 and early 1938 Holiday performed with the Count Basie Orchestra; following this she toured with Artie Shaw and his band, as one of the first Black women to perform with an all-white band. She endured repeated insults and discrimination while on tour, especially in the South, where restaurants and diners would not serve her. Shaw did his best to defend her and insist on equal treatment. He later said of her:

I never heard her hit a bad note that was off by even a sixteenth of a tone. She had a remarkable ear … and a remarkable sense of time …. She had her own thumb-print, when she sang it was unmistakably her … [when] she sang something it came alive, I mean, that’s what jazz is about. (Nicholson 107)

By the late 30’s and early 40’s Holiday had become an established artist in the recording industry and on the radio.

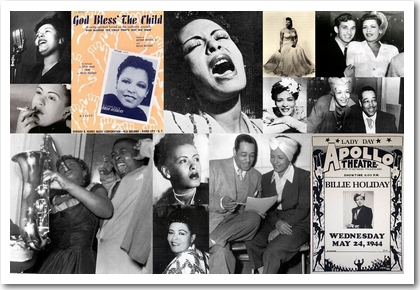

In 1939 Holiday first performed “Strange Fruit,” a powerful song by leftist Abel Meropol (aka Lewis Allen) about the lynching of Black men in the South. It begins with the lines:

Southern trees bear a strange fruit / Blood on the leaves, blood at the root / Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze / Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

Holiday’s performance at Café Society, New York’s first integrated night club, had a major impact on audiences and gave impetus to the anti-lynching movements of the era, though the song was forbidden to be broadcast on the radio and was rejected by Columbia Records as “too inflammatory.” Holiday insisted on recording it, however, and was finally able to do so for Commodore Records; it became her signature song and was later selected for the Grammy Hall of Fame (1978). Black scholar and activist Angela Davis argues that Holiday’s performance of this, “her most important song” and “the aesthetic centerpiece of her career,”

almost singlehandedly changed the politics of American popular culture and put the elements of protest and resistance back at the center of contemporary black musical culture. The felt impact of Holiday’s performance of “Strange Fruit” is as powerful today as it was in the 1940s. (Davis 183)

In 1941 Holiday met and married playboy James Monroe, a glamorous, violent ne’er-do-well, whose occupation was variously described as “sportsman,” “impresario,” “marijuana dealer” and “pimp.” In Billie, who reached her commercial peak during the 1940’s, he “saw a meal-ticket” (Nicholson 119). Monroe probably introduced her to opium, the drug of choice among the hip elite. When Monroe was convicted of drug smuggling, Holiday took up with Joe Guy, a musician who also supplied her with drugs (at outlandish cost). During the war years opium became scarce and was replaced by heroin; at first Holiday simply used it to get high, but by 1945 she was genuinely “hooked” (Nicholson 144).

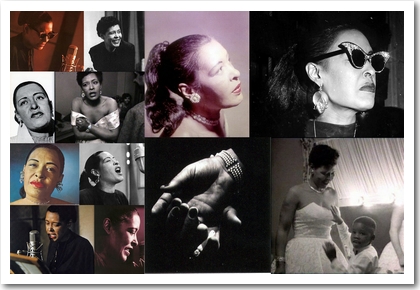

After her mother’s death in October of that year she sank into serious depression and began drinking and using drugs ever more freely. Haunted by a deep fear of loneliness, she became dependent on her male lovers to an abnormal degree, and was even more open to exploitation and abuse (Nicholson 147). Although at the height of her fame and earning power, she never had enough money, given her drug habit and the “friends” around her.

In 1947 Billie Holiday and Joe Guy were arrested and charged with receiving and concealing a narcotic drug; Guy was found innocent, but Billie, whose manager refused to arrange legal counsel for her, pleaded guilty and was sentenced to a year and a day at the Federal Reformatory for Women in Alderston, Virginia. Here she received medical treatment and successfully ended her drug dependency before she was released on parole. However, because of her felony conviction, she was denied the Cabaret Card which would permit her to perform in New York night clubs where alcohol was served. Deprived of her major source of income, Holiday was forced to find other venues and tour other cities. Surrounded once more by her old crowd of pushers and leeches, she soon relapsed. A second arrest for drug possession in 1949 ended in her acquittal.

During this particularly low point in her life and career (she was being exploited by her then lover-manager, John Levy), she turned to her “dearest friend,” the actress Tallulah Bankhead, who connected Billie with her own psychiatrist in California. Stuart Nicholson writes of Holiday’s long-standing relationship with Bankhead, whom she called “Lady Peel”:

Certainly both Lady Day and Lady Peel enjoyed living it up and both enjoyed hanging out together. Indeed, several musicians claim that Billie made no secret about her lesbian relationship with ‘Lula’ and, more sensationally, a brief, explosive affair with Marlene Dietrich. (174)

In the late 40’s and early 50’s Holiday enjoyed some spectacular comeback performances, such as at sold-out concerts in Carnegie Hall in 1948 and in 1954 a successful European tour and appearance at the first Newport Jazz Festival. Her relationship with Louis McKay, starting in 1950, seemed to give her a sense of security and the ability to shake off or at least reduce her drug habit for a time.

But the years of drinking, heavy smoking and drug use were taking a cumulative toll on Billie Holiday’s voice and health; she was increasingly unable to master new material or perform reliably. In 1956 she was again arrested for narcotics possession, this time with Louis McKay. They married in 1957 in order to avoid having to testify against each other. But McKay left when Billie took up with yet another manipulative and abusive pseudo-fan, the attorney Earle Zaidins.

On May 30 1959, after months of declining health – by now she weighed barely 95 pounds – Billie Holiday collapsed and was taken to the hospital. She was diagnosed with a liver ailment brought on by excessive alcohol consumption complicated by cardiac failure, followed by a kidney infection and congestion in the lungs. When a nurse discovered a white powder in the Kleenex box on Billie’s night-stand the police and FBI were called and she was arrested for possession. Her comic books, record player and records were taken away, and guards were posted at her door. But this time Billie Holiday eluded prosecution: she died, virtually penniless, on July 17 at age 44.

Author: Joey Horsley

Quotes

No two people on earth are alike, and it's got to be that way in music or it isn't music. (Lady Sings the Blues)

I'm always making a comeback but nobody ever tells me where I've been. (Lady Sings the Blues)

I hate straight singing. I have to change a tune to my own way of doing it. That’s all I know. (Billie Holiday)

Links

For web resources see the German version.

Literature & Sources

Blackburn, Julia. 2005. With Billie. New York: Pantheon. (Deutsch: Billie Holiday. 2006. Aus dem Engl. von Barbara Christ. Berlin: Berlin-Verl.)

Clarke, Donald. 1994. Wishing on the Moon: The Life and Times of Billie Holiday. New York: Viking. (Deutsch: Billie Holiday: eine Biographie = Wishing on the Moon. 1995. Aus dem Engl. von Barbara Schaden und Ingeborg Schober. München, Zürich: Piper.)

Davis, Angela. 1998. Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, Bessie Smith & Billie Holiday. New York: Pantheon.

Gourse, Leslie. 1997. The Billie Holiday Companion: Seven Decades of Commentary. New York: Schirmer.

Greene, Meg. 2007. Billie Holiday: A Biography. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Holiday, Billie, mit William Dufty. 1956. Lady Sings the Blues. New York: Doubleday. (Deutsch: 6., vom Übers. neu durchgeseh. und überarb. Aufl. 2013. Aus dem amerikan. Engl. und mit einem Nachwort versehen von Frank Witzel. Hamburg: Ed. Nautilus)

Margolick, David. 2002. Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday, Café Society, and an Early Cry for Civil Rights. Edinburgh: Canongate.

Nicholson, Stuart. 1995. Billie Holiday. London: Gollancz; Boston: Northeastern UP.

O’Meally, Robert. 1991. Lady Day: The Many Faces of Billie Holiday. New York: Little Brown.

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.