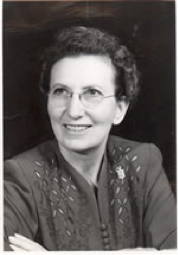

(Angie Elbertha Debo, PhD.)

Angie Debo

* January 31, 1890 in Beattie, Kansas

† February 21, 1988 in Enid, Oklahoma

U.S. historian and writer, author of nine books on American Indian and Western history

135th Birthday on January 30, 2025

Biography • Literature & Sources

Biography

“I violated history by telling the truth.”

And indeed she did. When Angie Elbertha Debo spoke these words near the end of her career, she was referring to the numerous books and many articles she had written or edited about American Indians, in which she tackled issues of harsh, often criminal mistreatment of Indians on the part of US institutions and government – a topic that previous historians had mostly “pussyfooted” around. In investigating what really happened to Indians and writing about them from their point of view, Debo contributed greatly to launching the “new Indian history.”

Angie was born on January 31, 1890, near Beattie, Kansas. Ten years later she traveled in a covered wagon with her parents and younger brother, Edwin, to live in the town of Marshall, in what was then Oklahoma territory. The family arrived a decade after the 1889 land run, in which much of the land was opened to white settlers. The Debos bought a farm, but the land turned out to be unproductive, and the family was poor. Angie always had a love of learning and yearned to attend high school. However, when she finished grade school, there was no high school in Marshall. Several years later, one was built; she attended it for a year, and then had to drop out to help her family financially. At sixteen she obtained a teacher’s certificate and taught for several years in local rural schools. She finally graduated from high school in 1913 at the age of twenty-three.

After two more years of teaching, Angie enrolled in the University of Oklahoma, obtaining a bachelor’s degree in 1918. While she was a student there, one of her professors, Edward Everett Dale, became her lifelong mentor and close friend, even though they did not share the same approach to American history. Dale, who had been a student of the eminent historian Frederick Jackson Turner, inherited Turner’s “frontier thesis,” which emphasized the advancing white settlement of western lands as a distinguishing feature of the young country’s history. Angie had a different perspective: she wanted to study history from the standpoint of the people who were already there – American Indians. Historian Ellen Fitzpatrick writes of “the largely blind eye historians had traditionally turned toward the story of America’s Indigenous people.” But Angie did gain from Dale an appreciation of the American West as a valid subject for study, as well as a commitment to accuracy in historical research.

Following another period of teaching, Angie enrolled in graduate school at the University of Chicago. She wanted to concentrate in history, but the field was not open to women. Instead she chose international relations, and earned a master’s degree in 1924. Her master’s thesis, which she co-authored with one of her professors – historian J. Fred Rippy, a scholar of imperialism in Latin America – was published by the University of Oklahoma press in 1924 under the title The Historical Background of the American Policy of Isolation. Her work on this book shaped her understanding of America’s attitude toward Indians as the country’s “real imperialism.”

Following another period of teaching, Angie enrolled in graduate school at the University of Chicago. She wanted to concentrate in history, but the field was not open to women. Instead she chose international relations, and earned a master’s degree in 1924. Her master’s thesis, which she co-authored with one of her professors – historian J. Fred Rippy, a scholar of imperialism in Latin America – was published by the University of Oklahoma press in 1924 under the title The Historical Background of the American Policy of Isolation. Her work on this book shaped her understanding of America’s attitude toward Indians as the country’s “real imperialism.”

In spite of her book publication and her advanced degree, when it came to finding a job, the fact that Angie was a woman was again not in her favor. While she was still at Chicago, the history department received requests from thirty colleges and universities seeking to hire history teachers. Angie later recalled, “Twenty-nine of them said they wouldn’t take a woman under any circumstances. One of them … would take a woman if they couldn’t get a man.” In 1924, she did gain a position in the history department at the West Texas State Teachers College. However, she was not granted a faculty post there; she actually taught in a high school affiliated with the college. Repeatedly passed over for promotion, in 1930 she decided to return to the University of Oklahoma to study again under Dale.

Angie wrote her doctoral thesis about the Choctaw Indians, one of the “Five Civilized Tribes” that early in the nineteenth century had been forced to move from their homelands in the southeast to eastern Oklahoma to make room for white settlers. Her methodology was unique – whereas other historians of Indians had mostly written military histories based on recollections of soldiers and government reports of federal Indian policy, Angie consulted archived tribal records, unpublished sources, and anthropological works. One of her main concerns was the injustice that had been done to the Choctaws as a result of the government’s policy of allotment. The Dawes act of 1887 had mandated the surveying of Indian lands and dividing them into allotments for individual Indians, as part of a plan to assimilate Indians into the dominant society. Senator Henry Dawes of Massachusetts, the author of the act, while praising some aspects of Indian culture, nevertheless criticized it because “there is no selfishness, which is at the bottom of civilization. Til this people will consent to give up their lands, and divide them among their citizens so that each can own the land he cultivates, they will not make much more progress.”

Allotment resulted in a great loss of land and resources for the Choctaws and other Indian tribes. Angie’s thesis, titled The Rise and Fall of the Choctaw Republic, was published as a book in 1934 by the University of Oklahoma press in a series initiated by the press’s director, Joseph Brandt, the Civilization of the American Indian Series. Not only was Angie the first woman on West Texas State’s faculty to hold a PhD., but her book on the Choctaws won the John H. Dunning award from the American Historical Association. Possibly for these reasons, as well as the antipathy of another (male) faculty member, in 1934 she was let go by the college.

Now unemployed, Angie returned to her parents’ home in Marshall and started investigating the history of the Five Civilized Tribes. Besides the Choctaws, these were the Chickasaws, Cherokees, Creeks, and Seminoles. These tribes, after being relocated to eastern Oklahoma despite having become “civilized” in their adoption of many attributes of white culture, had established their own governments and law courts, and farmed communal lands. But the Curtis Act of 1898, an amendment to the Dawes act, pushed further toward the goal of assimilation: Indians were forced to give up not only their communal lands but also their law courts and, essentially, their way of life. In 1927 the government undertook an extensive survey of conditions among American Indians – including those in Oklahoma. The report, called the Meriam Report, came out the following year. It documented abysmal social, health, and educational facilities and suggested that the policy of assimilating Indians into the dominant culture might not be the best course to take to solve the “Indian problem.”

Between 1934 and 1936, funded in part by a grant, Angie delved deeply into the often very disturbing history of the five tribes. Dale obtained access for her to government documents stored in the basement of the Department of Interior Building in Washington, D.C. She found that so-called grafters would take advantage of Indians in numerous ways, especially ones on whose land oil was found. There were instances of kidnappings, murders, and abductions of potentially wealthy children in order to become their guardians and gain access to their land and wealth. Angie stated later that when she started this project, she hadn’t known what she was getting into – that eastern Oklahoma and Oklahoma generally was “dominated by a criminal conspiracy to cheat these Indians out of their land.” Looking back, Angie said that doing this research was one of the most unhappy experiences of her life. She recalled, “It seemed as though everything I touched was slimy … I would walk through a kind of dark corridor, because I was working in basements mainly [of courthouses], on material that had never been used before. [And] I just felt afraid. I’d pick up a newspaper and here would be on the front page names of the people who had attained their power and prominence by robbing the Indians and this was criminal, too. And when I would look at the society page, here would be their wives and the other women in their family, and it just seemed as though it was a terrible experience.”

But Angie persevered and documented such crimes, as her biographer Shirley Leckie noted, “in dramatic, damning detail.” She began the preface with these words: “Every schoolboy knows that from the settlement of Jamestown to the 1870’s Indian warfare was a perpetual accompaniment of American pioneering, but the second stage in dispossessing the Indians is not so generally and romantically known. The age of military conquest was succeeded by the age of economic absorption, when the long rifle of the frontiersman was displaced by the legislative enactment and court decree of the legal exploiter, and the lease, mortgage, and deed of the land shark.” In her text, she frequently gave voice to Indians, quoting long passages of Indian testimony given to allotment committees and congressional investigations. In one such instance, she quoted a Creek man, Eufaula Harjo, who referred to the original treaty the American government had made with the tribe: “We full-blooded Indian people used to live east of the Mississippi River and we made a treaty with the white man. That treaty was made in 1832, on March 24….this land was given to us forever, as long as grass should grow and water run. It was given to us and the Government of the United States has divided the land up without the consent of the Indian people. The Indian people did not know anything about it until the land was cut up, and it was done without their consent.”

Angie submitted her manuscript to the University of Oklahoma Press in 1936. However, because of the potentially inflammatory nature of parts of the content – some of the people she accused were still alive, some even in the state legislature, and she had named names – the press feared libel suits. There was concern that publishing might jeopardize the press and antagonize wealthy donors to the university. Also, Angie was aware of the experience of Kate Barnard, whom she admired. Barnard, the first director of the Oklahoma Department of Charities and Corrections, had tried to protect Indian orphans from corrupt guardians and had lost funding for her department. The views of one supporter of Angie’s manuscript at the press, director Joseph Brandt, were not enough to prevail; the manuscript was rejected.

The following year, however, Brandt left for Princeton University Press, which – after removing possibly libelous material – published And Still the Waters Run: the Betrayal of the Five Civilized Tribes in 1940. Angie had been cautiously optimistic about such an outcome when she commented wryly, “the Princeton Press is not dependent upon Oklahoma politicians for appropriations.” Four decades later, in 1984, attitudes had changed – the University of Oklahoma Press finally published a paperback edition of the book. Brandt was proud of having published both Angie’s book on the Choctaws and her book on the Five Civilized Tribes. He predicted that Americans would come to realize that the latter book was “among the most significant histories to be published in this country,” but not until they understood that “the Indian is as important to our knowledge of ourselves as Greek or Roman civilization.” The book’s significance, as well as that of some of her other books on Indians, is further attested by the fact the scholarship in them has been used as evidence in court cases in support of Indian rights. Angie later reflected that this book was her most important work.

Angie hoped that, with her growing list of publications and credentials, Dale might hire her to teach at the University of Oklahoma, but again sexism prevailed – he did not hire her, even as a temporary replacement, although he hired male professors no more qualified than she was. Between 1934 and 1947, Angie had no stable employment, but she did have some work. Occasionally she did more high school teaching; in 1940 she applied for a position with, and became the head of, the Federal Writers Project in Oklahoma. The project was established to support writers during the Depression, part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Angie contributed to the Project’s WPA Guide to 1930s Oklahoma, published the following year. In 1947 she finally obtained a job as a curator of maps at the Oklahoma A & M University library.

Ironically, although Angie finally began to be offered a few university positions, she turned them down – she wanted to write instead. She wrote several more books about Indians, and edited others. These included a history of the Creek Indians, a general History of the Indians in the United States, and Geronimo: the Man, His Time, His Place, a biography of the great Apache leader, in which she countered his reputation as a savage, ruthless warrior with a thoughtful and sympathetic understanding of the man and his many tribulations. She also interviewed some of the full-blooded Indians living in remote parts of Oklahoma, and in 1951, on the basis of this fieldwork, published a pamphlet deploring their living conditions, The Five Civilized Tribes of Oklahoma: a Report on Social and Economic Conditions. Perhaps paradoxically, despite her highly critical views of the state’s treatment of Indians, Angie was also a great admirer of the Oklahoma people’s pioneer spirit and strength. This positive outlook was reflected in two books that she wrote about Oklahoma history and in a novel, Prairie City, based on life in Marshall and other nearby towns.

Ironically, although Angie finally began to be offered a few university positions, she turned them down – she wanted to write instead. She wrote several more books about Indians, and edited others. These included a history of the Creek Indians, a general History of the Indians in the United States, and Geronimo: the Man, His Time, His Place, a biography of the great Apache leader, in which she countered his reputation as a savage, ruthless warrior with a thoughtful and sympathetic understanding of the man and his many tribulations. She also interviewed some of the full-blooded Indians living in remote parts of Oklahoma, and in 1951, on the basis of this fieldwork, published a pamphlet deploring their living conditions, The Five Civilized Tribes of Oklahoma: a Report on Social and Economic Conditions. Perhaps paradoxically, despite her highly critical views of the state’s treatment of Indians, Angie was also a great admirer of the Oklahoma people’s pioneer spirit and strength. This positive outlook was reflected in two books that she wrote about Oklahoma history and in a novel, Prairie City, based on life in Marshall and other nearby towns.

When she was nearing her seventies, Angie did quite a lot of international traveling. She visited England and several European countries, followed by Russia, which she had long wanted to see. These experiences, as well as trips to Mexico and central Africa, broadened her perspective on race relations and civil rights in her own country. In her later years, Angie became an activist in support of indigenous people’s rights and related issues. She was critical of the Indian Relocation Act of 1956. This act was part of the policy of Indian Termination, which encouraged Native Americans who lived on or near Indian reservations to relocate to urban areas. Supposedly the reason was for greater employment opportunities, but Angie suspected the policy was another attempt to gain control of Indians’ land. She started sending annual Christmas letters to her friends, urging them to write to congressmen and senators in support of specific issues. The number of recipients all across the country increased to become her activist “network.” In regular newsletters, Angie backed measures for numerous indigenous tribes, such as land and water rights for Native Alaskans and for the Havasupai and Pima tribes in Arizona.

In other areas, Angie opposed the Vietnam war and strongly supported the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to protect the rights of protesters of the war. A feminist professor at Oklahoma State University, Gloria Valencia-Weber, in her eulogy of Angie, recalled that “she represented the ACLU in universities or other settings to defend the right to First Amendment protection for all regardless of their message ….She violated many of the expectations of her adversaries. I think perhaps they expected a scruffy, long-haired, bearded-hippie type, and in walked this wonderful woman with a grandmotherly appearance, incredible knowledge, superb credentials, and a sense of humor. Her adversaries simply did not know how to deal with such a knowledgeable and dignified hell-raiser.” On the other hand, Angie did not agree with the tactics of some of the more militant Indian rights groups such as the American Indian Movement (AIM). Nor did she participate in the feminist movement per se, but was rather her own feminist.

Most of Angie’s friends, colleagues, and adversaries were impressed by her strength of character. In her work she was regarded as a “lone wolf,” very independent and strong-minded. At the same time she had a deep sense of community and was always generous to her neighbors and to other scholars. One admirer noted that she “comforted the afflicted and afflicted the comfortable.” Angie never married, although as a young woman she had numerous suitors. She accepted that in the times she lived in, it would have been impossible to combine marriage and children with the profession she envisioned. Like Rachel Carson, she was very close to her mother; Angie and Lina Debo relied on each other for emotional and other support, until Lina’s death in 1954. Throughout her life, Angie felt grounded in and affectionate toward her home town of Marshall, leading Valencia-Weber to observe that she had “a life-long love affair with Marshall and its people.”

In the mid 1970s, Angie’s health began to decline. She developed osteoporosis and deafness. In 1976 she was diagnosed with colon cancer. She had surgery and recovered well (informing friends, with characteristic wit, that since part of her colon had been removed, she now had a semicolon). Her eyes were also growing weaker. As she carried out her research and interviews, Angie had driven all over Oklahoma and beyond; her last car, which she had had for twenty years, was becoming increasingly unreliable. Friends urged her to buy a new one, which she refused to do; then to stop driving, which she also refused to do, but she finally gave in. When friends arranged for her to be driven to meetings, she warned them that they’d better find safe drivers because “I have not finished Geronimo yet. I’m not doing anything dangerous until I finish that book.”

Over the years, Angie gradually gained recognition for her work. Beginning in 1950, Angie received many awards and honors. In 1958, Marshall showed its appreciation for her by holding an Angie Debo Recognition Day. She was inducted into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame in 1950, and – much later – into the Oklahoma Women's Hall of Fame in 1984. She received honorary degrees from Wake Forest University and Phillips University, and awards from several historical associations. In 1985, the State of Oklahoma commissioned an official portrait of Angie by artist Charles Banks Wilson; it was placed in the rotunda of the Oklahoma State Capitol building in Oklahoma City, near two of Oklahoma’s favorite sons, Will Rogers and Jim Thorpe. In 1987, she was given the Award for Scholarly Distinction by the American Historical Association, presented to her by Governor Henry Bellmon in a ceremony in January 1988 in Marshall, a month before she died.

Historian Ellen Fitzpatrick has remarked on Angie’s achievement in helping create a “new Indian history,” with Indians placed center stage. “In effect,” she writes, “Debo offered a reverse Turner thesis – one that joined the advance of the frontier with the diminution of democratic values and the emergence of a destructive American character.” Fitzpatrick also reminds us of the circumstances under which Angie worked: “Deprived throughout almost her entire life as a historian of the various privileges academic appointment would have conferred, Debo labored in painful isolation amid discouraging circumstances for the better part of sixty years to reveal the ways in which Native Americans experienced and made their own history.”

With the growth of the feminist and civil rights movements in the 1960s and 70s, scholars began to study in depth the lives of outstanding women. Valencia-Weber and a colleague, Glenna Matthews, conducted oral interviews with Angie. These led to an interest in making a film about her life. The result was “Indians, Outlaws and Angie Debo,” with Angie, then 98, telling her story. Sadly, she died before the film was released.

At the end of the film, Angie reflected that there was one particular quality she had that made all the difference in her life – “and that was drive.” Angie’s gravestone bears the words, “Historian, discover the truth and publish it.” She did that and more. Valencia-Weber observed that Angie Debo “compressed several lifetimes of accomplishment as a scholar, fighter for human rights, and a responsible community member who enriched the lives of many. She clearly left the world a better place than when she entered.”

Author: Dorian Brooks

Literature & Sources

Abrash, Barbara, “Case Study: Indians, Outlaws and Angie Debo,” Center for Media and Social Impact, http://cmsimpact.org/resource/case-study-indians-outlaws-and-angie-debo/

Fitzpatrick, Ellen, History’s Memory: Writing America’s Past, 1880 – 1980 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004).

Foreman, Grant, Indian Removal: the Emigration of the Five Civilized Tribes (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1932), Foreword by Angie Debo.

Leckie, Shirley A., Angie Debo, Pioneering Historian (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000).

Limerick, Patricia Nelson, “Land, Justice, and Angie Debo: Telling the Truth To – and About – Your Neighbors,” Great Plains Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 4 (Fall 2001), pp. 261-273, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23532948?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Schrems, Suzanne H. and Cynthia J. Wolff, “Politics and Libel: Angie Debo and the Publication of And Still The Waters Run,” Western Historical Quarterly, Vol. 22, No. 2 (May, 1991), pp. 184-203 http://www.jstor.org/stable/969205

Valencia-Weber, Gloria, “Eulogy: A Perspective on the Life of Angie Debo,” 1988 http://info.library.okstate.edu/c.php?g=151950&p=999447

Books by Angie Debo

The Historical Background of the American Policy of Isolation, by J. Fred Rippy & Angie Debo (Northampton, Mass.: Smith College Studies in History, 1924).

The Rise and Fall of the Choctaw Republic (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1934, 2nd edition, 1961), ISBN 0-585-19818-7.

And Still the Waters Run: The Betrayal of the Five Civilized Tribes (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1940; new edition, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1984), ISBN 0-691-04615-8.

The Road to Disappearance: A History of the Creek Indians (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1941; new edition, 1979), ISBN 0-8061-1532-7.

Tulsa: From Creek Town to Oil Capital (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1943).

Prairie City: The Story of an American Community (New York: Knopf, 1944; new edition, Tulsa: Council Oak Books, 1986; new edition, Norman: University Press of Oklahoma, 1998), ISBN 0-8061-2066-5 (a novel).

Oklahoma: Foot-Loose and Fancy-Free. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1949; new edition, 1987, ISBN 0-8061-2066-5.

The Five Civilized Tribes of Oklahoma: A Report on Social and Economic Conditions (Philadelphia: Indian Rights Association, 1951).

A History of the Indians of the United States (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970), ISBN 0-8061-1888-1, (new edition, 2013), available online at Googlebooks.

Geronimo: The Man, His Time, His Place (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976/1982), ISBN 0-8061-1828-8, almost all available online at Googlebooks.

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.