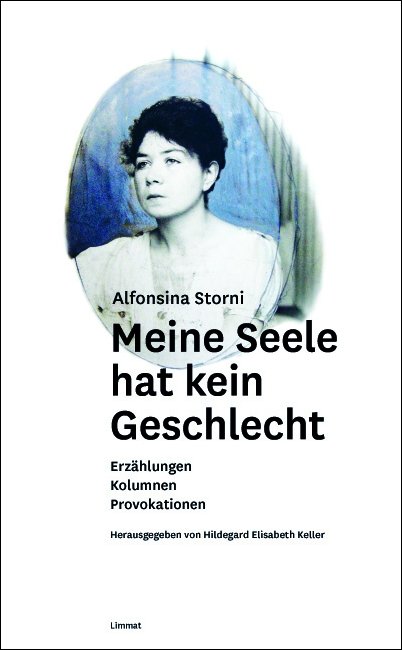

born on May 29, 1892 in Sala Capriasca/Ticino

died on October 25, 1938 in Mar del Plata/Argentina

Argentine poet

130th birthday on May 29, 2022

Biography

„Me faltaba un amor, y ya lo tuve una infamia tambien, y di con ella …”

“I lacked a love, I got it and a betrayal, he did not spare me ...”

On the homepage of Sala Capriasca in Ticino, where she was born in 1892, the name Alfonsina Storni appears under the heading “Personalities”; in Mar del Plata, Argentina, where she threw herself into the sea and drowned in 1938 at the age of 46, there is a large stone memorial to the poetess. Between the two dates lies a tragic life, the life of a highly gifted and highly sensitive woman who today would be called a feminist, but at the time was deeply wounded by the restrictions imposed on women by Latin America's male-dominated society.

Alfonsina is the third child of the Swiss couple Paulina Martignoni and Alfonso Storni. When Alfonsina is four years old, the family goes back to San Juan in Argentina, where the father had already built up a brewery with his three brothers in earlier years. The Stornis, initially wealthy and respected, run into increasing economic difficulties when the head of the family becomes alcoholic and increasingly depressed. The mother, an educated woman, then runs a private school and supports the family, with four children by now. A move to Rosario and the opening of the “Café Suizo” then leads to poverty.

Alfonsina helps out in the café as a child, often gets her family into trouble with her fantasy stories, called “lies,” and writes her first poem at the age of twelve. In her distress, she procures writing paper at the post office: blank telegram forms. In 1906, after the death of her father, at the age of thirteen, she initially works in a hat factory, but is then able to attend school in Coronda/Santa Fé, earn a diploma as an elementary school teacher, and start her first job in Rosario. When a scandal breaks out because she performs as a singer in a theater during her studies, she attempts suicide.

Her poems are already published in the local newspapers. In Rosario she meets a married politician and journalist, by whom she becomes pregnant. She is 20 years old and felt stigmatized by her gender. This is evident in her work Languidez [Desire], where she sighs “Señor, el hijo que no me nazca mujer [Lord, don't let the child be born a woman].” Giving birth to a non-marital child in a small town? She does not want to expose herself to this “shame”; she flees to Buenos Aires, where on April 21, 1912, her son Alejandro is born. Difficult years followed, during which she earned her living with various jobs, for example as a cashier in a pharmacy or as a stenotypist.

Her poems are already published in the local newspapers. In Rosario she meets a married politician and journalist, by whom she becomes pregnant. She is 20 years old and felt stigmatized by her gender. This is evident in her work Languidez [Desire], where she sighs “Señor, el hijo que no me nazca mujer [Lord, don't let the child be born a woman].” Giving birth to a non-marital child in a small town? She does not want to expose herself to this “shame”; she flees to Buenos Aires, where on April 21, 1912, her son Alejandro is born. Difficult years followed, during which she earned her living with various jobs, for example as a cashier in a pharmacy or as a stenotypist.

At the same time, she wrote poems and was able to publish them at her own expense in 1916. Her verses in La inquietud del rosal [The Impatience of the Rosebush] cost her the job, however, because it is considered offensive for a woman to write so openly about love and male relationships. Under the peculiar pseudonym “Tao-Lao,” she works for various magazines and newspapers, such as La Nación, and eventually becomes recognized nationally as a poet as well. She connects with literary and musically successful circles, publishes her third collection of poetry, and is awarded two literary prizes. Nevertheless, in Buenos Aires she feels lonely and misunderstood, disappointed and deeply sad. Death and the sea as the source of all life are recurring motifs in her poetry. She observes big city life, is constantly thinking about the purpose of her existence, and comments with sharp irony on gender relations. The play El amo del mundo [The Lord of the World], premiered in January 1927 in the presence of the president, is a flop: she criticizes men too bitingly, argues too cleverly for women's rights.

On the advice of a friend, she travels through Spain, Italy and France during the summer of 1930, giving readings and lectures to large audiences and making a brief visit to her Swiss birthplace. Four years later, together with her son Alejandro, she comes to Europe once again and is again successful.

In 1935, Alfonsina Storni suffered a severe stroke: she contracted breast cancer and had to undergo surgery and then chemotherapy. Under the medical conditions of the time, this was certainly a much greater psychological and physical strain than it is today. Her character changes, she withdraws from her old circle of friends, doesn't want pity. Her writing style also reshapes itself, becomes more abstract, surrealistic, reveals itself to the reader rather intuitively and remains incomprehensible to many. Mascarilla y trébol [Mask and Clover] is one of these late works.

In Montevideo, in 1938, there is a great poetry festival to which Alfonsina Storni is invited, along with the two celebrities Gabriela Mistral and Juana de Ibarbourou. Back on the other side of the Rio de la Plata, a few months later, she decides to put an end to her existence. She suffers unbearable pain, is worn down and disappointed by life. In Mar del Plata she rents a room in a small boarding house and writes her last poem Voy a dormir [Soon I will sleep]. On the night of October 25, she throws herself into the sea.

With her powerful voice, Mercedes Sosa sings the song Alfonsina y el mar in her memory. In Argentina, she has long been an icon, but in Switzerland, Alfonsina Storni has only recently been appreciated.

*** Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version), edited by Almut Nitzsche, May 2022 ***

Author: Elisabeth Brock

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.