(Anna Dorette Frieda Johanna Heise)

(Anna Dorette Frieda Johanna Heise)

Born 9 April 1895 in Gandersheim

Died 3 September 1986 in Hanover

German Photographer

Biography

Biography

“I must always be free!” Aenne Heise followed this motto her entire life, and it inspired the courageous step toward independence she took when she opened her own “Photography Studio” in 1924. Only the second woman to do this in Hanover, she was an exotic rarity in an otherwise male-dominated field. For almost 50 years she was active as a Gebrauchsphotographin (practical or commercial photographer), as she called herself. She worked in all branches of her profession and was proud of the fact that she did everything herself, from taking the pictures to processing them in the darkroom.

Heise was born on April 9, 1895 in Gandersheim to an upper middle-class family. After her parents’ early death she lived with various relatives and soon had to stand on her own two feet. She decided on a career as a nurse. Careers in the social services were considered appropriate for young women before they married and offered a secure livelihood if no husband materialized. Before she had even completed her training Heise was put to work as an assistant in a military hospital, for World War I had begun.

At the end of the war she changed her given name to Aenne. During this time she also had her first brush with photography as a student in a course at the “Bakteriologisch-chemische Lehranstalt für Damen” (Bacteriological-Chemical Training Institute for Ladies). She was able to apply the knowledge she gained there in microphotography in a military hospital in Lüttich in 1917. Thus her first photographic images were produced - more for a scientific purpose than out of artistic interest.

Full of enthusiasm for photography, Aenne Heise acquired the necessary practical skills immediately following the end of the first World War in the photo class just being instituted at the vocational training school in Braunschweig. She familiarized herself with the artistic, aesthetic side of her craft at the Kunstgewerbeschule am Lerchenfeld (school of practical or decorative arts) in Hamburg, to which she transferred in 1919. Here, in the workshop context, she was able to try out an artistic idea and realize it in practice. She showed an affinity to impressionistic photography in landscapes and portraits that she rendered in a picturesque, painterly style.

When Aenne Heise left the school with her Gesellenbrief (journey(wo)man’s certificate), she had acquired a solid training in all the photographic and reproductive procedures current at the time. Living in Hamburg during the “wild” twenties, she had gotten to know the free artistic and cultural life of the big city – as well, of course, as the financial insecurity that went along with it. For that reason she also took care, while still an art student, to secure a second source of income. She trained for work as a waitress at “Strecker’s Dienerfach-Schule und Servier-Lehranstalt” (Strecker’s Servant and Wait-Staff Institute).

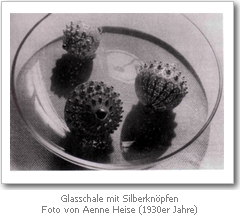

Heise’s one-woman business, which she opened at age 28 in her first combined studio and apartment in Hanover, was the decisive step towards a self-determined, independent life. Since she refused to retouch her photos in the laboratory, she preferred to document crafts- or artistic objects; she was less fond of portrait photography. She produced pictures for product catalogues for the Hanover firm Günther Wagner (later Pelikan-Works). Soon she had made a name for herself in the fields of fashion, decorative arts, interior decoration, and architecture. She also soon became a member of GEDOK, the “Gemeinschaft Deutscher und Oesterreichischer Künstlerinnenvereine aller Kunstgattungen” (Association of German and Austrian Women Artists’ Organizations in all Art Fields), and always considered herself as an artist who emphasized the technical as well as the aesthetic aspects of her craft. An enthusiast for the latest technology, Heise was an early owner of the Leica, a practical, easily operated camera that used rolls of film and permitted a series of 36 photographs without changing the negative material. Thus equipped, she would be on her way in her “rolling studio,” an open, reseda-green Adler sports car, to fulfill commissions or shoot photos for local newspapers and magazines. Her broad professional success was certainly unusual for a woman at the time. She followed the motto: “What I do, I do thoroughly!”

Among Heise’s clients was the organization “Deutsche Frauenkultur” (German Women’s Culture), later gleichgeschaltet (“coordinated”) or subsumed under the National Socialist umbrella organization of non-party women’s groups and renamed “Frauenkultur im deutschen Frauenwerk” (Women’s Culture in the German Women’s Front). Her fashion fotos and photographs of decorative objects as well as photos of children in rural settings appeared in the magazine of this organization. Most likely she believed, in the years after 1933, that she could serve her art and her photographic object exclusively, free of any political partisanship. But she also saw no problem, when she was commissioned by the Luftwaffe to photograph in the northern and eastern regions of what was then the German Reich both arts and crafts objects and scenes from officers’ mess rooms. Pictures from this time, such as a child’s cradle with the sentence “the child ennobles the mother” carved on it in runic letters, are mostly viewed critically today. There is no evidence in her surviving work or papers, however, that she produced photographs for Nazi organizations which served an exclusively propagandistic purpose.

Soon after the Second World War Heise began to receive commissions from her old customers. And once reconstruction began to clear the rubble of postwar Germany a whole new field of activity opened up for her in the flourishing construction industry. She worked for prominent architects and as an industrial photographer. When black-and-white photography was replaced by color photography in the 1960’s she apparently felt that she could no longer manage the developing and printing of her films in her own laboratory, and colleagues took over this work. Aenne Heise gradually withdrew from commercial photography and gave up her craft officially in 1971.

In 1985 the “Handwerksform Hannover” exhibited pictures from Heise’s fifty-year-long career as a photographer. She at first intended to make new prints from her old negatives for this presentation, but gave up the idea. She died a year later at age 91.

Aenne Heise was a co-founder in 1949 of the consortium “Kunsthandwerk in Niedersachsen” (Decorative Arts in Lower Saxony). Her photographic estate of several thousand pictures is located in the Historical Museum in Hanover.

trans. Joey Horsley

For additional information please consult the German version.

Author: Barbara Fleischer

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.