(Tillie Lerner Olsen)

born 14 January 1912 in Omaha, Nebraska, USA (earlier sources listed her birth year as 1913)

died 1 January 2007 in Oakland, California, USA

US-American author, essayist, college teacher and activist on behalf of human rights and social justice; a formative voice of second wave feminism

10th anniversary of death on 1 January 2017

Biography • Quotes • Weblinks • Literature & Sources

Biography

for Mary Anne Ferguson

Though her literary output was limited in quantity, the short stories and unfinished novel of Tillie Olsen are considered by many to be literary masterpieces. In her fiction, essays and charismatic talks, moreover, Olsen introduced themes that would become central to a generation of women readers and writers: she brought the subject of motherhood into focus as a valid topic for literary representation, even as she showed how it, along with economic “circumstances” and the restrictions imposed by race, class and sex, presented a major obstacle to women’s artistic creativity. Speaking and writing during the 1960’s, 70’s and 80’s about the “silences” imposed on women, racial minorities and working class writers, Olsen drew on her own experience to open new perspectives on the literary canon. Her impetus led to a movement to recover lost and neglected writers of the past, encouraged other women to tell their stories and made Olsen herself a revered icon of the women’s movement. She also was an outspoken advocate of human rights, racial and social justice.

Many details of Tillie Olsen’s life have only recently come to light, thanks to the exhaustively researched biography of Panthea Reid (Tillie Olsen: One Woman, Many Riddles, 2010). Earlier sources had listed her birth year as 1913, for example. Mother Ida (Hashke) Goldberg and father Samuel Lerner were Russian secular Jewish immigrants who had opposed the czar, remained committed to socialist ideals and never married; it is unclear why they never registered the births of their first two daughters. Having grown up herself in a patriarchal Jewish household, Ida had strong views about women’s equality, which she transmitted to her children along with the couple’s socialist values. The second of six siblings, Tillie was born in Omaha, Nebraska, a meat-packing center with a large Jewish immigrant population. Both Sam and Ida were active in Workmen's Circles, a national Jewish socialist organization, and Sam was later State Secretary of the Nebraska Socialist Party. Tillie and her siblings experienced anti-immigrant discrimination, intensified by their relative poverty and their parents’ pacifism during World War I.

Tillie Lerner was a lively and precocious child who charmed her parents with her wit and talent, but whose wild behavior and rebellious desire for independence were soon beyond their control. Articulate despite a stutter, Tillie gained popularity by producing a humor column in the high school newspaper, writing as “Tillie the Toiler.” As an aspiring writer she read voraciously (socialist literature found in the family home, later Emily Dickinson, Katherine Mansfield, Virginia Woolf, Sappho, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche), but often exasperated her teachers and dropped out of school in the 11th grade. Her biographer cites examples of Tillie’s penchant for telling lies, as when she falsified her age in school: ”Altering reality was intoxicating, as was ‘being unpredictable’” (Reid 38). The young Tillie wrote about feeling a “terrible force” that kept her writing at a mad rate, and about wild mood swings: “‘It’s very trying being exalted one day and so desperate the next.’” (Reid 46). She was sexually adventurous and had an abortion or miscarriage at age 16; when her parents attempted to discipline her with housework and summer school classes she moved out to live with an artist.

Tillie Lerner’s adult life was no less full of both exuberance and despair, commitment and distraction. Charismatic and beautiful, she joined the Young Communist League (YCL) in 1930, to the disapproval of her socialist parents, and met and secretly married Abraham Jevons Goldfarb, a leftist writer and activist 17 years her senior. Under the directives of the YCL she wrote, organized, participated in strikes, worked in a tie factory and at other jobs. When she became very ill, she was given a reprieve by the YCL and allowed to recover in Faribault, Minnesota at the home of her husband’s relatives.

During this respite she was able to write, and began work on a novel about the Holbrooks, a poor family struggling to eke out a living in the 20’s and early 30’s, first in a coal-mining town in Wyoming, then on a tenant farm in South Dakota, finally in a meat-packing center modelled on Omaha. The novel remained unfinished but was eventually published in 1972 as Yonnondio: From the Thirties. It captures the pain and futility of the American midwestern rural and urban poor in vivid, psychologically wrenching scenes that show the crushing effects of poverty on father, mother and children. Although the narrative perspective shifts repeatedly and includes poetic, stream-of-consciousness passages, the experiences of mother Anna and daughter Mazie receive the most development and offer the few momentary examples of hope for a better life.

Tillie and Abe’s daughter Karla was born in December, 1932. The family soon moved to California to work for the Communist Party. During this period Tillie was torn between her writing and political activism, with her dedication to the goals of the party usually winning out. “‘When it comes to painting slogans or plastering up stickers a madness overcomes me.’” (Reid 97) Despite the fact that she was courted by leftist editors who saw in her the promise of a new proletarian literature – Philip Rahv printed the first section of her novel (as “The Iron Throat”) in his Partisan Review – and publishers such as Bennett Cerf of Random House, Tillie did not produce more of the promised book. She stalled publishers for years, taking their advance payments and telling them she was making progress, while instead she took part in strike actions, got arrested and jailed, and wrote political brochures.

She also neglected her daughter, pawning her off on relatives and allowing her to become ill and emaciated when under her charge. By 1936 she had broken up with Abe Goldfarb and begun a relationship with Jack Olsen, a party comrade and labor organizer. Both had participated in the 1934 West Coast waterfront strike and been jailed for their activities. Tillie later tried to erase all mention of Goldfarb in her biography; his mysterious death in a suspicious auto accident (1937) appears to have left her with long-lasting guilt feeings (Reid 130). She and Jack Olsen would eventually marry and have three daughters.

In the late 30’s and 1940’s Tillie Olsen was kept from writing by the burdens of raising a family and earning a living; she also became actively involved on behalf of women and children, for example as president of her PTA chapter and of the California CIO Ladies’ Auxiliary (Reid 146). Despite having served on government boards to assist with wartime social and economic issues, Tillie was, along with Jack, targeted by the FBI during the “red scare” witch hunts of the early 1950’s; both lost their jobs and lived in fear of being arrested.

During this difficult period in Tillie Olsen’s life the desire to write resurfaced with overwhelming force, as is evident from private notes she wrote to herself:

... My conflict - to reconcile work with life ... Time it festered and congested postponed deferred and once started up again the insane desire, like an aroused woman…. conscious of the creative abilities within me, more than I can encompass ...1953-54: I keep on dividing myself and flow apart, I who want to run in one river and become great…. (Reid 190).

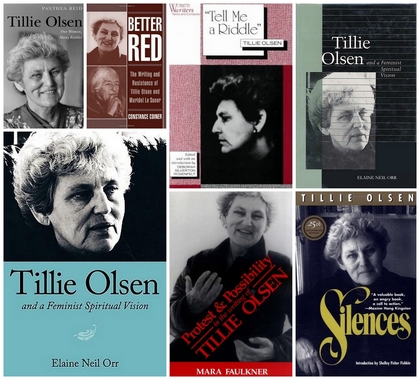

Olsen now began to craft stories based on her daily observations, encouraged by creative writing classes at San Francisco State College and a prestigious Stegner fellowship at Stanford University (1955-56). She wrote her best known stories during this time, including “I Stand Here Ironing,” a mother’s anguished reflections about her troubled daughter’s childhood and her own maternal inadequacies. In 1960 Olsen published “Tell Me a Riddle,” a novella based on her Russian immigrant mother’s last illness and death. It received the O’Henry prize for best American short story the following year and in 1980 was made into a film with Melvin Douglas and Lila Kedrova and directed by Lee Grant.

Once again Olsen’s talent was recognized and she was sought after by publishers (e.g., Malcolm Cowley of Viking Press) who expected her to produce more stories and a great novel. Once again, a combination of economic and family burdens and emotional lability prevented her from delivering what she had promised. She felt the pressure of such expectations all the more when she was awarded a two-year Ford Foundation grant in literature in 1959, along with James Baldwin, Bernard Malamud, Flannery O'Connor, and Katherine Ann Porter (Reid 215). Reid speculates that Olsen’s long hospitalization early in 1961 may have been the result of a “crack-up” and could have involved shock treatment (219). Following the hospitalization, Olsen referred to her “new small shattered brain” and empathized with Virginia Woolf’s bouts with manic depression (Reid 220).

A friendship with and recommendation from the poet Anne Sexton, with whom she shared a sense of precarious mental equilibrium (Reid 218), brought Olsen to the Bunting (later Radcliffe) Institute for Independent Study (1962-64), where she read and researched other women writers and hoped to work toward her goal of a novel blending larger social issues with the story of her family. In a talk to the Radcliffe fellows Olsen thematized her lifelong struggle with the “circumstances” that kept her from writing, expanding to the larger question why women in general, as well as the less privileged, were not more fully represented in literature. Her examination of the social causes of such underrepresentation – based on race, class, gender – together with other essays and notes would later be published as Silences (1978, 2003). Olsen’s impassioned call to redress the balance (only “one in twelve” acknowledged writers was a woman) came at the very time feminism was beginning to stir after the conservative 1950’s; first articulated in 1963, the year when Betty Friedan’s seminal The Feminine Mystique appeared, it set off an unstoppable wave of production by women authors and feminist literary scholars.

Olsen herself advocated effectively on behalf of such “lost” writers as Rebecca Harding Davis and Agnes Smedley, whose work she persuaded Florence Howe to republish as the first two recovered texts of her new Feminist Press. Davis’ 1861 story “Life in the Iron Mills” appeared in 1972 with a long biographical introduction by Olsen, and Smedley’s autobiographical novel Daughter of Earth, first published in 1929, came out the following year. In addition to her essays and talks, Olsen developed reading lists of works by women writers which were eagerly adopted by feminist teachers of literature and the emerging field of women’s studies.

Olsen, now established as a prize-winning author and feminist icon, was showered with grants and visiting professorships, including NEH and Guggenheim grants, fellowships at the MacDowell Writers’ Colony in New Hampshire, visiting positions at MIT, University of Massachusetts Boston, Amherst College, UCLA, University of Minnesota and Kenyon College. She was awarded at least six honorary degrees and was celebrated in 1981 when then Mayor Diane Feinstein proclaimed May 18 “Tillie Olsen Day” in San Francisco. She maintained a hectic pace, appearing on podiums around the country (and abroad, as Norway’s international visiting scholar in 1980); as in earlier years, Olsen’s extraordinary public engagement both energized and exhausted her and again impeded actual writing.

Panthea Reid’s recent biography paints a complex portrait of this celebrated author and revered pioneer of second wave feminism. Repeatedly Reid quotes family members, editors and friends, and Olsen herself to the effect that the author-activist often seemed near to mental or emotional breakdown; described as zany, hysterical, narcissistic and unable to think logically, Olsen also suffered anxiety, guilt and depression at not producing the works she felt called to. Reading the account of her restless moves from one abode to another (including a nomadic phase in a motor home), of her unbridled, promiscuous sexual behavior, her tendency to embellish the truth and claim attention, her rapid speech and stutter, her sense that words and ideas were pouring out of her, one increasingly suspects the presence of some degree of manic depressive illness. If Olsen did suffer from such a condition it could help answer the question that nagged her biographer and many others of why she did not produce more writing. Of course, as Kay Redfield Jamison argued in Touched with Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament (1993), such a condition would also be consistent with the exuberant drive to be a great writer and right the wrongs of the world that fed Tillie Olsen’s outspoken brilliance and creative achievements as well.

Author: Joey Horsley

Quotes

“Silences will, like A Room of One's Own, be quoted where there is talk of the circumstances in which literature is possible.” (Adrienne Rich)

“Tillie Olsen helps those of us condemned to silence—the poor, the racial minorities, the women—find our voices.” (Maxine Hong Kingston)

Links

A Tribute to Tillie Olsen (Link)

The Tillie Olsen film project. Tillie Olsen - A heart in action. A Film by Ann Hershey. (Link)

Bosman, Julie: Tillie Olsen, Feminist Writer, Dies at 94. New York Times, January 3, 2007. (Link)

Coiner, Constance (1995): Tillie Olsen's Life. From: Better Red – The Writing and Resistance of Tillie Olsen and Meridel Le Sueur. New York: Oxford UP, 1995. (Link)

Cusac, Anne-Marie: Tillie Olsen Interview. The Progressive, November 1999. (Link)

Internet Movie Database: Tillie Olsen. (Link)

Martin, Abigail: Tillie Olsen (Digital Collections, Albertsons Library). (Link)

Nebraska Center for Writers (NCW): Tillie Olsen (Link)

Literature & Sources

Coiner, Constance. 1995. Better Red: The Writing and Resistance of Tillie Olsen and Meridel Le Sueur. New York: Oxford University Press.

Frye, Joanna S. 1995. Tillie Olsen: A Study of the Short Fiction. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1995.

Nelson, Kay Hoyle, and Nancy Huse. 1994. The Critical Response to Tillie Olsen. Westport, Conn. Greenwood Press.

Olsen, Tillie. 1961. Tell Me a Riddle: A Collection. Reprints of “I Stand Here Ironing,” “Hey Sailor, What Ship,” “0 Yes,” and “Tell Me a Riddle.” Philadelphia and New York. J. B. Lippincott, 1961.

Olsen, Tillie. 1974. Yonnondio: From the Thirties. New York. Delacorte Press/Seymour Lawrence.

Olsen, Tillie. 1978. Silences. New York. Delacorte Press/ Seymour Lawrence. (Rpt 2003. New York. The Feminist Press.)

Pearlman, Mickey, and Abby H. P. Werlock. 1991. Tillie Olsen. Boston: Twayne Publishers.

Reid, Panthea. 2010. Tillie Olsen: One Woman, Many Riddles. New Brunswick, NJ and London. Rutgers.

Rosenfelt, Deborah Silverton, Hg. 1995. “Tell Me a Riddle” by Tillie Olsen (Women Writers, Texts and Contexts Series). New Brunswick, N.J. Rutgers University Press, 1995.

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.