Biographies Notburga von Rattenberg

* 1265 in Rattenberg

+ (13 September?) 1313 in Rattenberg

Tyrol’s only female saint

Biography

The popular Tyrolean saint Notburga, a dedicated young serving maid, twice succeeded in making it onto an Austrian postage stamp, in 1999 for 20 groschen and in 2008 for 55 cents. The veneration of this beloved saint has a long and rich tradition. As protector of female agricultural workers and the peasantry in general she is called upon in many situations of distress, from human or animal sickness to threatening storms.

Notburga was born in 1265 in Tyrol (then part of Bavaria) to a simple family of miliners. When she was 18 she came to Schloss (Castle) Rottenburg, where she served as a kitchen maid. She was capable and pious and was highly regarded by her employers, Count Heinrich I and his countess. She distributed bread and wine to the poor and was greatly beloved for her benevolence. When Heinrich II and Countess Ottilia became lord and lady of Schloss Rottenburg, however, they forbade the servant, also an excellent cook, to care for the poor and drove her from the castle. Notburga packed her things and left Schloss Rottenburg. She went to St. Rupert’s Chapel (the “Rupertskirchl”) in Eben on the other side of the Inn River, which she had often been able to see from the castle. After she had negotiated with a farmer in Eben, the so-called “Spießenbauer” (skewering peasant), that she would not have to work on Sundays or holidays, she took a position with him as a servant, where she remained for five years.

During these five years much sadness occurred at the proud castle Rottenburg. Many residents departed, the pigs were ravaged by swine fever, Ottilia’s half-brother set the castle on fire, Ottilia sickened and was near death. When Notburga learned of this she hurried to the Rottenburg and offered the countess reconciliation; Ottilia gratefully accepted before departing her earthly life. After the countess’ death Notburga went back to Eben. Once Count Heinrich had remarried and begun a happy life with Margarethe von Hoheneck, he asked Notburga to return to the castle. She accepted his offer, but only after he had agreed to let her resume her care for the poor. For 18 years she served in the castle as cook and as nanny for Margarethe’s five children, all the while continuing her charitable good works unhindered. A document from 1337 reports that the Rottenberger counts had pledged themselves to provide for at least 300 poor persons, a number later even raised to 500. Before her death Notburga was also successful in reconciling the two alienated brother counts of Rottenburg.

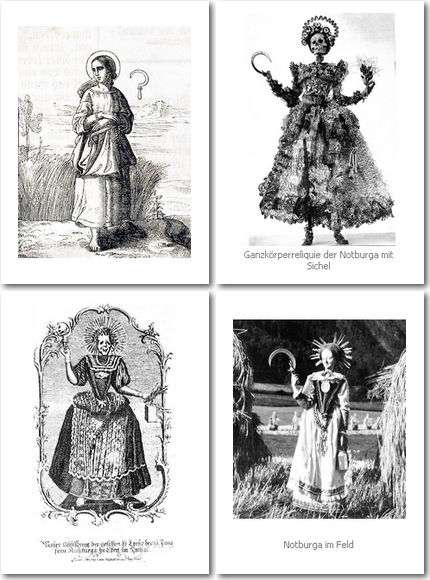

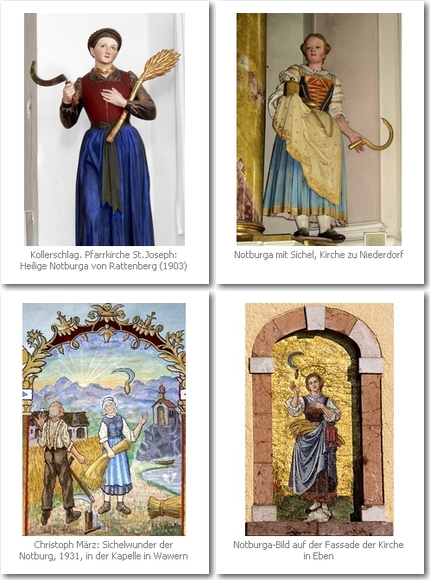

The saint is especially revered in the pilgrimage church St. Notburga in Eben on Lake Achen in Tyrol. The high altar of the late baroque church displays a splendid reliquary shrine containing the skeleton of the saint. Notburga is shrouded in costly gold-embroidered robes and accompanied by her attributes – in her raised right hand she holds the sickle, while her left hand grasps her bread-filled apron and a pitcher hangs from her arm.

The significance of this saint can be seen from the fact that her image is not only found in paintings, votive images and engravings, as statues on altars, in the stained glass of church windows, on offering boxes, church bells, and medallions, on holy water basins and pilgrimage coins – but also in objects of everyday use such as salt shakers, stove tiles, cupboards, silk prayer book inserts. There are even tiny, 2 by 2.8 cm. vertical pictures of her to be swallowed or “inhaled” from; they were used as part of religious folk medicine and belonged in the home apothecary. It was believed that consuming or breathing in from these little images would release the healing power of St. Notburga most powerfully and transfer it incarnate to the sufferer. Little silver Notburga sickles were worn on watch chains and rosaries as amulets. Many songs, prayers and litanies further testify to the people’s intimate relationship to their saint.

The legends have it that Notburga performed three miracles, each reflecting a different aspect of this saint. The first one entered history as the wood shavings miracle. Notburga was on her way to bring bread and wine to the poor and encountered Count Heinrich II with his horse and entourage; to expose her as a thief, he commanded her to open her apron, only to discover it contained nothing but wood shavings. Notburga the social worker.

The next miracle is probably the best known: the so-called miracle of the sickle, featuring Notburga the trade unionist. Once, when she was working in the fields, the farmer insisted that all field hands work past the normal quitting time, since he wanted to finish the harvest. Notburga alone showed the courage to lay down her sickle, reminding him that her contract provided for regular hours. The farmer was unrelenting, and so Notburga called upon God to provide a sign. Sure enough, when Notburga raised up her sickle it remained floating in the air.

The third miracle occurred after Notburga’s death: Notburga, the mystic. Following her wishes her coffin was placed on a cart and oxen were to pull it to whatever place divine providence would dictate for her to be buried. When the cart, starting from Rattenberg, reached the Inn, the river parted and the entire funeral procession was able to cross to the other shore without harm. The procession continued to Eben, where the oxen finally stood still in front of Saint Rupert’s Chapel. Angels were said to have lifted the coffin from the cart and to have strewn flowers from heaven.

This Rupertskirchl, a wayside chapel on the steep path to Eben, was expanded after Notburga’s death; in the 16th centtury Emperor Maximilian had the church reconstructed. In 1735 Notburga’s mortal remains were transferred to the church in Eben as a full-body relic. Pilgrimages began in earnest during the first half of the 17th century. There are reports that pilgrims took earth from the saint’s grave away with them. Worshippers contributed votive tablets, the nobility donated land to the church as well as altar furnishings and priestly vestments. Natural produce such as lard for the eternal light as well as food for pastors and pilgrims were generously provided by the local peasants.

Notburga devotées went on pilgrimages not only in Tyrol, but also to many locations in in Styria, in Bavaria, in Slovenia, Croatia and Istria. In Eben on the Achensee and in Jagerberg in Styria such pilgrimages are still undertaken. In Weissling near Kollbach in Bavaria there are many votive tablets which testify to the saint’s veneration. In south Tyrol there was a Notburga pilgrimage in the vicinity of Bolzano, near Badl above Schloss Kampenn. Notburga altars grace churches in St. Andrä and Bruneck, iin Pfunders and Stilfes. In Hörschwang by Onach in the Puster valley there is a small pilgrimage church dedicated to St. Notburga which possesses one of the oldest votive tablets, from the year 1686.

The feast day of St. Notburga is September 13, in some regions also the 14th. In 1862 Notburga was made a saint by Pope Pius IX, who affirmed the folk veneration of her as a holy woman. The feast of St. Notburga has been celebrated each year since 1862 on the Sunday after September 13; it is attended by many visitors from near and far.

A number of authors have searched for prechristian origins of St. Notburga. The region around the fish-rich Lake Achen has many legends, and a sacred site of Berchta (Perchta) is said to have existed on its shores. Notburga’s characteristic sickle suggests that she might have replaced an earlier moon goddess. Her association with fields, crops, grain and bread recalls the “grain mothers” (“Kornmütter”), the fertility goddess Demeter and the Roman Ceres. The bringer of death can also be seen in the serving maid: Notburga, the reaper, who – like the Athropos (Greek Moirai), the Morta (Roman Fates), the Skuld (Germanic Norns) – severs the thread of life.

The St. Notburga Promenade and the steep Notburga path in the vicinity of Eben offer hikers a quiet opportunity to converse with the beloved saint.

(translated by Joey Horsley)

For additional information (bibliography and links) please consult the German version.

Author: Ingrid Windisch

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.