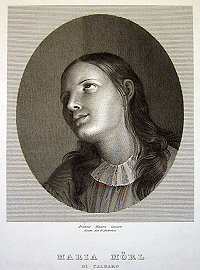

(Maria Theresia von Mörl)

Born 15 October 1812 in Kaltern, South Tyrol, Italy

Died 11 January 1868 in Kaltern, South Tyrol, Italy

South Tyrolean stigmatic (bearing the marks of the wounds of Christ since 1834)

Biography • Literature & Sources

Biography

Biography

Because of her, 40,000 persons came during a single summer to Kaltern, a small wine village south of Bolzano. The roads were poor and food and lodging for the pilgrims meager, but they all wanted to see her, the young aristocrat with eyes turned heavenward and delicate, folded hands who hovered over her bed. In a time when Protestantism and modernism threatened to unsettle the holy land of Tyrol, she was a welcome figurehead in defense of traditional Catholic values. In a time that followed upon the disturbances of war and the Enlightenment, people were only too eager to be uplifted and edified by the ecstatic virgin. It is probably no coincidence that in the same year seven more young female ecstatic stigmatics made news in Tyrol – a short time earlier one would hardly have noticed them, since they weren’t needed. _None of the other stigmatics in Tyrol became so famous as Maria von Mörl, however; none received such illustrious visitors. The publicist Josef Görres devoted 30 pages to her in Über christliche Mystik (Concerning Christian Mysticism), a work of his old age; the poet Clemens Brentano was among her admirers and visited her several times; and numerous representatives of the Austrian imperial and Italian royal families paid their respects to her. The Pope sent his secretary, and countless bishops came from Europe, England, and America. *** Maria von Mörl was born in 1812, the second daughter of Maria Katharina Sölva and Joseph Ignaz von Mörl von Pfalzen zu Mühlen und Sichelburg. Most likely it was no love-match: the mother was 17, the father in his early 20’s when they married; she was from a middle-class family, he from old Tyrolean aristocracy. When Maria was first admitted to Holy Communion at age 10, “she appeared to have feelings of such deep faith and heartfelt love that, as soon as she received the sacred Host, she collapsed in a faint” (according to her first biographer, Maria von Buol in the little book Herrgottskind (Child of God). Maria’s Mother bore a child almost every year; she died in childbirth with the 11th. Maria was then 13 years old. It was her responsibility, as the oldest daughter, to care for her siblings and the household – her father preferred to go hunting. Three of her siblings died during childhood; three would later enter a monastery/convent. Except for one brother, who took over the inheritance and married, the rest remained single – and in need of lifelong care. Maria von Mörl was herself sickly from early childhood on; several biographers report that when her father came home at night in an inebriated condition he would toss her out of bed for no reason and beat her. They also assert that she never held this against him.

When she was 17 Maria von Mörl was assigned her own father-confessor, who concerned himself almost exclusively with her. She entrusted herself to Pater Johannes Kapistran Soyer’s (not uncontroversial) spiritual guidance until her death in 1865. For a long time he was the only one who could send her into and release her from her ecstatic state. He required flagellation of her and flagellated her himself until her blood spattered the walls. Since her condition seemed to be caused by demonic torments, such punishment made sense, given the context of how mysticism was understood at the time, according to theologian Nicole Priesching: flagellation and self-martyrdom were not only an attempt to become one with Christ’s suffering, but also to do penance for her father and for the misdeeds of others in general.

Exorcisms were also undertaken with her several times, after she had spewed horse hair, nails and needles and had tried to throw herself out of the window. Here we see the devil functioning as part of the plan of salvation: he puts people to hard tests, but if they endure they are that much closer to their salvation. “After being strengthened by Holy Communion she was terribly tormented by it because of a wrongdoing that was committed in that same night. Her desire to suffer grew stronger; she was again admonished to obey me, so that I should continue to martyr her, which would happen without injury to (her) chastity, which God has assured her in His crown.” So writes her confessor in his diary for 10 November 1833. The sufferings of Maria von Mörl are without doubt worthy of further investigation. The physical abuse by her father could have been sexual in nature, and her ecstatic (hysterical) seizures the result of sexual repression and sexualized violence (so-called sexual abuse), just as Janet and Freud theorized as the source of hysteria. In this context it is also not insignificant that 90 percent of the approximately 600 stigmatics worldwide are women. Although she had been a member of the Franciscan Third Order, a secular order, for years, Maria von Mörl moved into the convent of tertiary sisters in Kaltern only after the death of her father. Once there, she hardly ever left it, and she never spoke to the occasional visitors who were now only selectively admitted. She died on January 11, 1868, in her 56th year and in the 36th year “of her ecstatic contemplation” – as is reported in the chronicle of the tertiary sisters. She had always prayed that her stigmata would no longer be visible after death: On January 8, three days before her death, only scars remained on her fine soft skin. In death these too had disappeared. The question remains open and perhaps does not even have to be answered: when is something hysteria and when is it mysticism? Can an hysteric not also be a mystic, and a mystic not also an hysteric?

Author: Astrid Kofler

Literature & Sources

For additional information please consult the German version.

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.