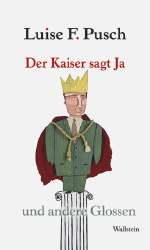

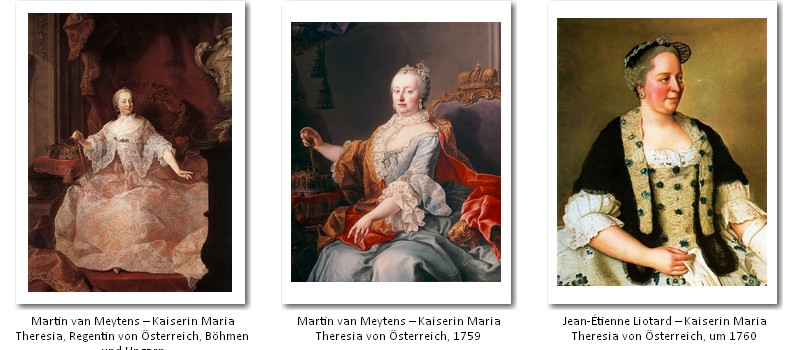

(Maria Theresia Walburga Amalia Christina of Austria; Empress Maria Theresia; Queen of Hungary, Bohemia, Croatia, Dalmatia, Slavonia, Archduchess of Austria, Duchess of Styria, Carinthia und Carniola, Silesia, Burgundy, Brabant, Limburg, Luxemburg, Geldern, Milan, Mantua, Piacenza und Guastalla, Grand Princess of Transylvania, Princely Countess of Tyrol, Flanders, Hinaut, Gorizia and Gradisca, Margravine of Moravia, Margravine of the Holy Roman Empire at Burgau, at Upper- and Lower Lusatia, Countess of Namur, Frau auf der Windischen Mark und zu Mecheln, widowed Duchess of Lorraine and Bar, Grand Duchess of Tuscany)

born on May 13, 1717 in Vienna

died on 29. November 1780 in Vienna

Austrian empress

305th birthday on 13 May 2022

Biography

The young heiress to the throne is desperate. No sooner has 23-year-old Maria Theresa - already a mother of three, with a fourth child on the way - taken over the reins of government from her recently deceased father, Charles VI, than her new position is already being contested by powerful European monarchs. A woman on the Austrian throne, which has also been the seat of the Holy Roman Emperor of the German Nation for 300 years? The Venetian envoy at the Viennese court is not the only one who believes “that it is incompatible with the dignity of a state to be ruled by a woman.”

The greatest adversaries have already picked out choice tidbits from the Habsburg Empire to usurp as soon as possible, above all Karl Albrecht, Elector of Bavaria, the Spanish King Philip V and the Saxon Elector Friedrich August II. However, Frederick II of Prussia reacted most quickly. Always considered a weakling by his father because of his fondness for the French language and culture, for music and philosophy, he wanted to show what a man he was immediately after his accession to the throne by annexing the populous and economically prosperous Silesia into his fragmented kingdom. On December 16, 1740, only two months after Maria Theresa's enthronement, he ordered his troops to march into Silesia.

This was precisely what Emperor Charles VI had wanted to prevent, and to this end he had issued the Pragmatic Sanction in 1713. This stipulated that the Habsburg Empire was to be inherited indivisibly as a whole. If there were no male heir to the throne, his daughters and their descendants would be entitled to inherit first, followed by the daughters of his brother Joseph. Charles VI had the Pragmatic Sanction guaranteed to him by the other European rulers.

This was precisely what Emperor Charles VI had wanted to prevent, and to this end he had issued the Pragmatic Sanction in 1713. This stipulated that the Habsburg Empire was to be inherited indivisibly as a whole. If there were no male heir to the throne, his daughters and their descendants would be entitled to inherit first, followed by the daughters of his brother Joseph. Charles VI had the Pragmatic Sanction guaranteed to him by the other European rulers.

Charles VI's only son had died after only seven months, and despite the hope of another male descendant, it became increasingly likely that Maria Theresa, as the eldest daughter, would succeed him. Nevertheless, she was not prepared in any way for her future role and duties. Her education consisted mainly of languages and history, musical education and dance. Thus unprepared and supported only by her father's aged advisors, Maria Theresa found herself faced with the challenge of preserving her huge and complex empire between the Oder and the Croatian Adriatic coast, between Bruges and Kronstadt/Transylvania, against the advances of jealous powers who summarily ignored Charles' bequest.

It was not wars that had made the Danube monarchy so large - that would hardly have been possible given the desolate state of the Austrian army - but a strategically shrewd marriage policy that had brought with it small and large estates as dowries or inheritances. However, the kingdoms, dukedoms and principalities of this multiethnic state did not regard themselves as a single community; they lacked a common language. Rather, the individual entities, down to the smallest domains, sought their own advantage and the greatest possible independence from the emperor in Vienna. This was especially true in the case of the Kingdom of Hungary, which remained on Austria's side only out of fear of renewed Turkish attacks.

In the selection of a marriage candidate for Maria Theresa, not only strategic reasons had played a role, but also interventions from abroad. The groom should not be too important, so that Austria-Hungary would not become even more powerful. For this reason, the Spanish prince initially envisaged was out of the question. The choice finally fell on Franz Stephan of Lorraine, who only with a heavy heart - “no cession, no archduchess” - renounced his duchy in favor of Maria Theresa. Fortunately for both parties, the marriage was a love match that produced sixteen children within 20 years. Six of them, however, died in childhood or adolescence. Franz Stephan was the prince consort at Maria Theresa's side, and did not interfere in the affairs of government, but helped her with the selection of competent advisors and with his talent in financial matters.

With the Prussian foray into Silesia, Maria Theresa's position seemed hopeless. Against the thoroughly drilled and well-organized Prussian soldiers, the Austrians hardly stood a chance. But Maria Theresa let Frederick II know that “the queen has no intention of beginning her reign by dismembering her states,” and she pressured the Hungarian nobility into providing an army by the promise of greater independence and privileges. England helped with money; moreover, the disagreements among her opponents played to her advantage. Thus, to everyone's astonishment, the young monarch was able to decide the War of the Austrian Succession in her favor. She had to give up Parma, part of Lombardy and, above all, Silesia. With her fierce courage, however, she won the respect of the European rulers and the affection of the Viennese.

In 1745, she achieved the election of Franz Stephan as Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. By this time, the title had become merely decorative; it had long since ceased to be associated with a position of power. Nevertheless, Maria Theresa traveled to Frankfurt am Main for the coronation festivities, her only trip abroad. However, she refused to be crowned empress by her husband. Her titles as crowned queen of Hungary and Bohemia and as archduchess of Austria, which she bore in her own right by inheritance, were sufficient for her. She did not want a conferred title; nevertheless, she used it in official decrees. For her national children, she is “the empress” in any event.

The war showed that the Habsburg monarchy was in many respects still stuck in medieval structures and far from a modern state like Prussia. Maria Theresa knew that she had to make reforms at various points. She was not a revolutionary, but cung to the old ways, to “God's grace” and to the privileges of power. But she also recognized that without concern for the people, no progress for the state as a whole was possible. For she also saw herself as a mother of the country who felt responsible for the common people, the peasants and the soldiers.

The prevailing tax system was particularly unjust, since the propertied classes avoided paying any taxes and placed the entire tax burden on the socially lower classes. Maria Theresa succeeded in reforming the tax system and, in the face of fierce resistance from those affected, also made nobles and clergy pay higher taxes. Given the experience of the War of Succession, the increasingly full state coffers initially benefited the military. The army was reorganized, from the Court War Council to the enlisted men. A military academy was founded to train officers. The common soldiers were to be drilled with military discipline and uniform orders - as well as receive adequate accommodation and rations.

A modern state needs a functioning administration. Maria Theresa strengthened the centralized leadership emanating from Vienna vis-à-vis the noble estates in the individual countries of the Habsburg Empire. She provided for an independent judiciary and a clear definition of the respective official competences. The creation of a cadastre (property register) led to more efficient land use and economic planning. In the former pleasure palace of Favorita, Maria Theresa established an academy for the training of loyal civil servants. Elementary schooling was introduced for the lower classes and compulsory schooling for children from the age of six to twelve.

Maria Theresa saw herself as an absolute ruler, albeit by the grace of God, and not as the first servant of her state like Frederick II. Like the other monarchs of Europe, she also insisted on a magnificent residence. With great zeal and following her own suggestions, she had the palace and park at Schönbrunn, located at the gates of the city, converted and expanded into a summer residence and the center of court life.

Maria Theresa saw herself as an absolute ruler, albeit by the grace of God, and not as the first servant of her state like Frederick II. Like the other monarchs of Europe, she also insisted on a magnificent residence. With great zeal and following her own suggestions, she had the palace and park at Schönbrunn, located at the gates of the city, converted and expanded into a summer residence and the center of court life.

As progressive as Maria Theresa was in the modernization of the state, she persistently held on to her traditional views and values in terms of ideology. Catholicism was the state religion, which Maria Theresa also practiced with prayers, devotions, retreats and fasting days. In contrast to Frederick II (“all religions are equally good, if only the people are honest. If Turks and pagans came and wanted to populate the country, we would build mosques and churches for them”) she denied non-Catholics civil tolerance in her Austro-Bohemian lands - Jews and Protestants were persecuted and had to leave their hereditary lands. Maria Theresa was a strict opponent of the Enlightenment; for her, tolerance was synonymous with indifference, which threatens custom and tradition. With this in mind, she ordered the state censorship authority to burn all books and writings that contradicted this raison d'état. A “Chastity Commission” pursued real or supposed immorality with unrelenting severity. Even “contre dances” (couples dances) were considered “immoral” and were not permitted outdoors in public. But even the children of Maria Theresa loved to dance “the German” (= waltz). With the same vehemence Maria Theresa opposed Freemasonry, to which adhered, to her regret, her husband Franz Stephan, son-in-law Prince Albert of Saxony-Teschen and her personal physician Gerard van Swieten.

After her extensive state reforms, Maria Theresa saw herself well equipped to take up the fight for Silesia again. She succeeded in drawing France, Prussia's old ally, to her side and winning the Russian Tsarina Elisabeth as an ally. The latter had long been annoyed by Frederick II's misogynistic remarks and would gladly take East Prussia from her enemy. But this new “Seven Years' War” (1756-63) ended in a draw after Elizabeth died unexpectedly in 1762 and her successor, Tsar Peter III, an admirer of Frederick, declared himself neutral. Territorially, everything remained the same, but faced with 120,000 people senselessly driven to their deaths and the realization that Silesia was lost forever, Maria Theresa became an opponent of war as a political tool.

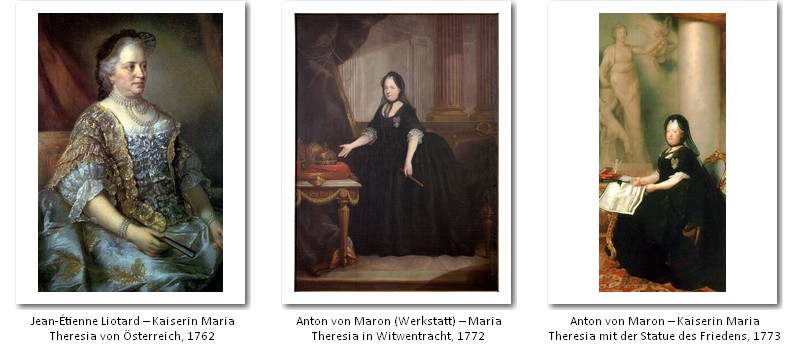

When her beloved husband Franz Stephan died in 1765, Maria Theresa had her bedchamber lined with gray silk and gave away her jewelry to the ladies of her court. For the rest of her life she wore black widow's clothes and a widow's veil. She often descended into the Capuchin crypt to sit at the sarcophagus of her deceased husband. She proclaimed her eldest son, later Emperor Joseph II, co-regent. Even though Maria Theresa had the last word, this joint regency harbored much potential conflict, for Joseph was open to the Enlightenment, and his mother's greatest adversary, Frederick II of Prussia, was his role model. Her stubbornness, which increased with age, became a further problem.

Despite this - or perhaps because of it - numerous other reform projects could be pushed through: To promote the economy, factories were built and customs barriers within the Habsburg Empire were removed to create a market for local products. The port of Trieste was expanded for the Habsburgs' own East India trade. A stock exchange was established and paper money was issued. A regular postal service for letters and passengers now connected the most important cities of the Empire. To increase the population, peasant families were recruited from several southern German cities and lured to sparsely populated Transylvania with travel money, free seed for planting, draft cattle and agricultural equipment. They were not only expected to cultivate the land, but also to serve as a bulwark against the neighboring Ottoman Empire.

Maria Theresa founded an academy for oriental languages and had a new building constructed for the university. Under van Swieten's supervision, the medical faculty especially achieved widespread fame and recognition. The appointment of medical officers as well as new hospitals and pharmacies were intended to improve the health of the population.

Maria Theresa founded an academy for oriental languages and had a new building constructed for the university. Under van Swieten's supervision, the medical faculty especially achieved widespread fame and recognition. The appointment of medical officers as well as new hospitals and pharmacies were intended to improve the health of the population.

Although Maria Theresa herself did not think much of the theater - she was more inclined toward Italian opera and chamber music, but “extravaganzas are necessary” - she had the National Theater established in the Viennese Palace. She was also the founder of Milan's La Scala.

Finally, the Prater, a magnificent park, was opened to the general public, which did not please every lady and gentleman “of standing.” But of greatest importance to the common people: Serfdom was ended and torture was abolished.

No matter how much Maria Theresa saw herself as a benevolent mother of her country, she had a firm grip on the education of her own children and their preparation for a future in a European ruling house. For although she herself had the great good fortune to enter into a love match, she always chose for her daughters and sons the spouses who promised the greatest advantage for the House of Habsburg. The eldest (surviving) daughter Maria Anna remained unmarried, as she was no longer considered “placeable” due to her having survived smallpox, and only the favorite daughter Marie Christine was allowed to choose her own husband.

Joseph II, who wanted to emulate his role model and also earn military laurels, set out with his army across the Inn River in 1778 to occupy Bavaria. Maria Theresa was desperate; she did not want war, nor did she want to annex Bavaria. She was at first even opposed to the (first) Polish partition. However, when Frederick II and Czarina Catherine II offered her Galicia with its capital Lemberg as a substitute for the lost Silesia (“one wrong cannot be cured by another”), she finally agreed.

Maria Theresa did not live to see the death by guillotine of her youngest daughter Maria Antonia - wife of the French King Louis XVI and known in France as Marie Antoinette. After 40 years on the throne, Maria Theresa of Austria died on November 29, 1780, and was buried in a double sarcophagus in the Capuchin Crypt next to Francis Stephen. During her reign, she earned the respect of other European rulers, even Frederick II, who had long underestimated her: “I fought wars with her, but I was never her enemy. She did all honor to her throne and her gender.”

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version), edited by Almut Nitzsche and Joey Horsley, May 2022

For additional information please consult the German version.

Author: Christine Schmidt

Quotes

We are in this world so that we may do good to others [...], we are not in the world for our own sake and to enjoy ourselves, but to gain heaven, to which everything aspires and which you do not get for free; you have to earn it.

I felt very comfortable with this way of acting, because all the world does more out of inclination than out of a mere sense of duty. If people are satisfied, they perform twice as much; if they act out of fear, they do nothing but just their duty.

The prince has no other rights than the private citizen.

When you are on the road, you have to act according to the peoples with whom you are staying: rural, moral.

One must have the courage to sacrifice oneself in order to judge justly.

Better a mediocre peace than a glorious war.

Be warned and never marry a man who has nothing to do.

The more you give your husband freedom, the more lovable you will be to him and the more he will seek you. Try to entertain him, to keep him busy, so that he will be nowhere better. The more freedom you give your husband, the more he will be attached to you. All happiness in marriage consists in trust and constant favors. Foolish love soon passes away; but one must respect the other, be useful to each other wherever possible. One must prove himself the true friend of the other, in order to be able to bear the accidents of this life and to establish the welfare of the home.

Without a religious foundation man is nothing and all virtues do not last.

If anything evil has happened under my government, it has certainly happened without my will, for I have only ever meant well.

She never refused an audience to anyone, and no one ever left her without being satisfied. She established her rule in all hearts by an affability and popularity which few of her ancestors had ever possessed; she banished formality and stiffness from her court.

(Voltaire)

When Maria Theresa was about to be delivered, a. e. of Maria Antoinette, she worked to the last moment, and replied to Doctor Van Swieten, when he made ideas to her: “My subjects are my first children, to them I owe my next care, with the rest it has time.” .

(Source)

A year later (Nov. 29, 1780) Maria Theresa died. She left the state in a much better condition than it had been in 1740. Not only had the unity and strength of the state grown, but progress had also been made in economic matters: Industry and commerce took off.

(Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon (1905), Vol. 15, p. 192)

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.