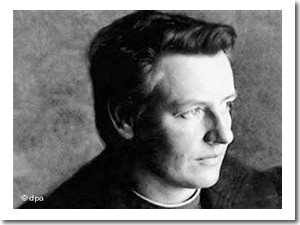

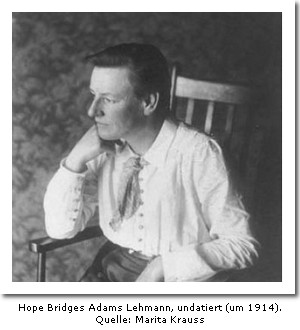

Biographies Hope Bridges Adams Lehmann

(Dr. Hope Bridges Adams Lehmann, Hope Bridges Adams [Geburtsname], Hope Adams Walther [Ehename])

Born December 17, 1855 in Halliford (near London)

Died October 10, 1916 in Munich

British-German physician and social reformer

165. birthday December 17, 2020

Biography • Literature & Sources

Biography

Hope Bridges Adams Lehmann was a visionary social reformer who was almost forgotten until the publication of her biography by Marita Krauss (2002).

Hope came from a progressive English family. It is not known why the 17-year-old moved to Dresden with her mother in 1873 following the death of her father.

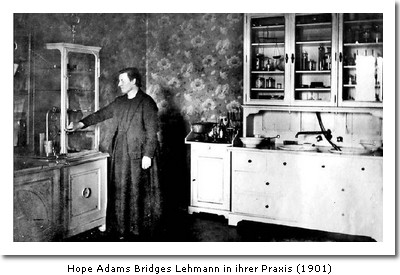

With incredible energy and tenacity, Hope pursued her medical studies from 1876/77 all the way through to the state examination, which she passed at the same time as her male counterparts – and as the first woman in Germany, despite massive obstacles from professors, fellow students and authorities. She went on to complete her doctorate in Bern, Switzerland, and earn her license to practice medicine in England; she then joined the practice of her husband, Otto Walther, on an equal footing with him.

After the birth of her second child, she fell ill with tuberculosis but was able to heal herself with a regimen of mountain air, hiking, rest, and targeted weight gain. The couple put that experience into practice by opening a sanatorium for lung disease in Nordrach in the Black Forest, which soon gained international renown.

After the birth of her second child, she fell ill with tuberculosis but was able to heal herself with a regimen of mountain air, hiking, rest, and targeted weight gain. The couple put that experience into practice by opening a sanatorium for lung disease in Nordrach in the Black Forest, which soon gained international renown.

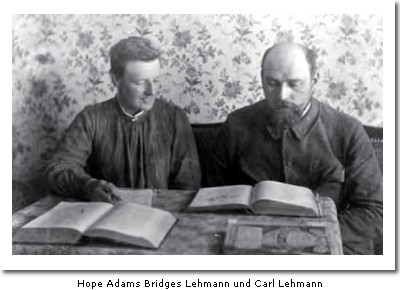

Hope fell in love with Dr. Carl Lehmann, ten years her junior and an administrator in Nordrach (his sister Maria became a dentist; she was married to the Austrian writer Franz Blei). When Hope demanded a divorce, her husband resisted vehemently, probably not least because he needed her in the clinic.

Carl and Hope opened a practice in Munich that soon flourished. Both of them were Social Democrats (Hope translated Bebel's “Woman and Socialism” into English). Hope also had good contacts with the Munich women's movement (including the “radical” couple Augspurg and Heymann) and was especially friendly with Clara Zetkin, whose two sons, Maxim and Kostja (later Rosa Luxemburg's lover), often stayed with the Lehmanns.

Carl and Hope opened a practice in Munich that soon flourished. Both of them were Social Democrats (Hope translated Bebel's “Woman and Socialism” into English). Hope also had good contacts with the Munich women's movement (including the “radical” couple Augspurg and Heymann) and was especially friendly with Clara Zetkin, whose two sons, Maxim and Kostja (later Rosa Luxemburg's lover), often stayed with the Lehmanns.

In 1896, Adams Lehmann published a “medical guide for women,” the two-volume “Women's Book” (“Frauenbuch”). She also planned to open a women's hospital called Frauenheim (women's home). Hope's views on hospital reform were visionary: “Thus should… the members of the ‘Frauenheim’ sponsoring organization, which the patients joined, elect the chief physician.  Through their membership, they would find themselves in a building that belonged to them and not in an institution, according to Adams Lehmann. Class-based medicine was to be abolished; poor and rich, single and married women alike could enjoy the same level of comfort in this hospital. Added to that was a call for transparency in medical work: patients were to be informed about the reasons for treatment, outcomes and type of procedure and be given a written copy to take home.” (Krauss 127)

Through their membership, they would find themselves in a building that belonged to them and not in an institution, according to Adams Lehmann. Class-based medicine was to be abolished; poor and rich, single and married women alike could enjoy the same level of comfort in this hospital. Added to that was a call for transparency in medical work: patients were to be informed about the reasons for treatment, outcomes and type of procedure and be given a written copy to take home.” (Krauss 127)

Equally revolutionary and groundbreaking were Adams Lehmann's ideas on education reform, which she first tried to implement in an experimental school and then – when this was not approved – in an experimental kindergarten. Anticipating modern-day insights in brain science and linguistic research, she wanted “to give children more intellectual stimulation than the ordinary kindergarten does.” Even three-year-olds should be familiarized with reading and writing in a playful way and, in addition, learn foreign languages from native-speaking kindergarten teachers at an age when this is still easily possible.

Although many prominent figures in Munich supported the ambitious Frauenheim project, midwives and parts of the medical profession feared the competition. The midwives eventually went so far as to involve Hope Bridges Adams Lehmann in an abortion trial, from which she emerged unpunished in 1915, but which did serious damage not only to her reputation but also to her health.

Although many prominent figures in Munich supported the ambitious Frauenheim project, midwives and parts of the medical profession feared the competition. The midwives eventually went so far as to involve Hope Bridges Adams Lehmann in an abortion trial, from which she emerged unpunished in 1915, but which did serious damage not only to her reputation but also to her health.

In April 1915, Carl Lehmann, a giant of a man and an experienced and passionate mountaineer, died of sepsis during the war. Hope was outwardly composed yet broken. Her tuberculosis returned. She put her estate in order and followed her husband a year and a half later.

(German text from 2004; transl. Julie Niederhauser 2020)

For additional information please consult the German version.

Author: Luise F. Pusch

Literature & Sources

For additional information please consult the German version.

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.