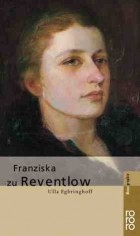

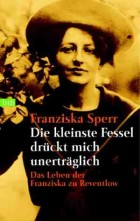

Biographies Franziska Gräfin zu Reventlow

(gesch. Lübke, verh. von Rechenberg-Linten)

divorced Lübke, married von Rechenberg-Linten

born May 18, 1871 in Husum, Germany

died July 26, 1918 in Locarno, Switzerland

German writer

Biography • Quotes • Literature & Sources

Biography

Franziska Countess zu Reventlow, whose dates—1871-1918—coincide with those of the Wilhelmine German Empire, has traditionally been pigeonholed as the scandalous bohemian of the Schwabing circles in Munich around the last turn of the century. Public attention has focused largely on her defiant personal rejection of conventional morality as she presented herself as a practitioner of free love and single motherhood. Yet she was also an author whose works captured the tensions of the pre-WWI generation and contributed to the lively debate about women’s liberation around 1900.

Fanny, as she was called as a child, was born into a north German noble family of traditional morals and stiff etiquette. Her rebellious nature prevented her from following the expected path of behaving like a young lady, marrying an appropriate nobleman and traveling in German high society. Instead, she was in constant conflict with her mother and managed to get thrown out of boarding school for misbehavior and lack of respect for the authorities. She joined a circle of like-minded young rebels who enthusiastically admired Ibsen’s revolutionary family dramas, ardently discussed Bebel’s book on women and socialism, and whole-heartedly supported Nietzsche’s call for the “re-evaluation of all values.”

Fanny, as she was called as a child, was born into a north German noble family of traditional morals and stiff etiquette. Her rebellious nature prevented her from following the expected path of behaving like a young lady, marrying an appropriate nobleman and traveling in German high society. Instead, she was in constant conflict with her mother and managed to get thrown out of boarding school for misbehavior and lack of respect for the authorities. She joined a circle of like-minded young rebels who enthusiastically admired Ibsen’s revolutionary family dramas, ardently discussed Bebel’s book on women and socialism, and whole-heartedly supported Nietzsche’s call for the “re-evaluation of all values.”

Reventlow ran away from home as soon as she came of age, had numerous affairs, and married a non-aristocrat in Hamburg who financed her attendance at an art school in Munich. Her marriage did not survive her wild and eccentric lifestyle in the “German Montmartre.” Having also been financially cut off by her family, Reventlow henceforth lived permanently at the edge of poverty and supported herself through jobs ranging from unsuccessfully trying to sell milk or insurance to more successfully prostituting herself in a high class brothel. Often toying with the idea of becoming, for financial reasons, a luxuriously kept woman she simply could not give up her overwhelming, even compulsive desire for freedom and independence and her distaste for monogamy: “Der Rausch verfliegt, und was dann?—Die Räusche verfliegen auch, aber es kommen neue” (“The intoxication fades away, and then?—Multiple intoxications fade away too, but new ones will follow”).

Her fluctuating love and living situations took Reventlow to Greece, Italy, and eventually to Switzerland. By 1910, her financial situation had become desolate enough to force her to leave Munich for Ascona, where she agreed to a mock marriage that was supposed to guarantee her second husband’s inheritance. Unfortunately, the little money that was gained in this deal was lost when her bank collapsed. At the age of forty-seven Reventlow died in Locarno from injuries incurred in a bicycle accident.

In 1897, Reventlow had given birth to her beloved son Rolf. With unparalleled nonchalance vis-à-vis conventions and prejudices, she made a point of raising him as a single mother, was hailed for this as a pagan madonna with child by her “Kosmiker” friends, and did not hesitate to commit perjury to avoid being assigned a male legal guardian. She purposefully kept her son out of both the patriarchal school system and the draft service to the fatherland: her teacher’s certification allowed her to homeschool Rolf, and then in 1917 she helped him desert by rowing across Lake Constance to Switzerland. Reventlow glorified motherhood and a symbiotic mother-child relationship as it presented the perfect solution for her need to feel the warmth and security of one single stable human bond which, at the same time, did not infringe on the freedom of her love life.

Franziska zu Reventlow’s artistic but unfulfilled passion was painting, not writing. Although she was a diligent correspondent and diarist, she did not acknowledge her talent for writing as more than another way to make ends meet. She translated 8000 pages of works by Maupassant, Prévost, and France and sold jokes and short prose pieces to the famous satirical journal Simplicissimus. Today, Reventlow is known for her semi-autobiographical novels and published letters and diaries, which shed light on the non-conventional side of Wilhelmine Germany. Reventlow’s autobiographical novel Ellen Olestjerne (1903) describes the author's childhood and youth and the painful conflict between a repressive education and her unsatiable hunger for life (Nietzschean vitalism). Another work—fashioned after letters of the famous seventeenth-century French courtesan Ninon de Lenclos—exhibits Reventlow’s controversial philosophy of free love that liberates women from being mere objects of men’s desire and ironically plays with the possibilities of role reversal, of a woman contemplating various types of lovers, e.g., the savior, the “elegante Begleitdogge” (elegant canine companion), or the gentlemanly, charming stranger. Further works present satirical observations of Munich's bohemian scene around 1900.

Franziska zu Reventlow’s artistic but unfulfilled passion was painting, not writing. Although she was a diligent correspondent and diarist, she did not acknowledge her talent for writing as more than another way to make ends meet. She translated 8000 pages of works by Maupassant, Prévost, and France and sold jokes and short prose pieces to the famous satirical journal Simplicissimus. Today, Reventlow is known for her semi-autobiographical novels and published letters and diaries, which shed light on the non-conventional side of Wilhelmine Germany. Reventlow’s autobiographical novel Ellen Olestjerne (1903) describes the author's childhood and youth and the painful conflict between a repressive education and her unsatiable hunger for life (Nietzschean vitalism). Another work—fashioned after letters of the famous seventeenth-century French courtesan Ninon de Lenclos—exhibits Reventlow’s controversial philosophy of free love that liberates women from being mere objects of men’s desire and ironically plays with the possibilities of role reversal, of a woman contemplating various types of lovers, e.g., the savior, the “elegante Begleitdogge” (elegant canine companion), or the gentlemanly, charming stranger. Further works present satirical observations of Munich's bohemian scene around 1900.

By publishing on taboo topics such as women’s erotic desire, single motherhood, and searing girlhood experiences in a hierarchical education system, Reventlow drew public attention to women's private experiences, thus reevaluating and helping to politicize these seemingly unpolitical issues. While some of her topics overlap with issues emphasized by the contemporary women’s movement, she distanced herself from and resented any association with the “Bewegungsweiber” (movement women), whom she detested for what she saw as their prudish puritanism. She was friends with outspoken feminists, such as lawyer, actress, and founder of the International Women’s League for Peace and Freedom, Anita Augspurg; however, she neither supported women’s suffrage nor women’s desire to compete with men on a professional level. Furthermore, rather than aiming at restricting men’s sexuality by abolishing prostitution, as did large parts of the bourgeois women’s movement, Reventlow considered traditional marriage the ultimate kind of prostitution and provocatively demanded the same respect for free expression of women’s sexual desires as for men’s. The discrepancy between Reventlow’s practical insistence on absolute independence and self-determination on the one hand and her advocacy of women’s erotic, but not economic emancipation on the other makes for a contradictory stance vis-à-vis traditional and avant-garde roles for women. Thus, she does not fit neatly into the categories of emancipated or unemancipated women. Many critics have dismissed Reventlow as a representative of a merely erotic rebellion. Yet, she went beyond simply living a self-confident affirmation of female sexuality. Her writings about personal experiences, non-conformist views, and controversial behavior represent important contributions to the public discourse on gender roles and expand the topic of literary hedonism—hitherto a domain reserved only for male authors such as Wedekind or Schnitzler—to include a woman’s perspective.

Scholars have focused on Reventlow’s life more than on her writings and have interpreted her ever-changing romances mostly in psychological terms, as resulting from a repressive childhood and conflicts with her mother. This much is true: Reventlow’s personal rebellion did not always correlate with the collective rebellion of the growing women's movement, she did not present herself as politically-minded, she was explicitly not a feminist, and her occasional social criticism was apparently motivated by individual needs rather than social involvement. Nevertheless, her writings do have political implications. By publicly treating taboo topics as she did in her literary works and by explicitly applying Nietzsche's call for the re-evaluation of all values to both sexes, she provided models of women’s independence and self-determination regarding marriage, sexuality, and motherhood and helped to subvert some of the anti-hedonism, anti-individualism, and blind allegiance to authority then prevalent in imperial Germany.

Scholars have focused on Reventlow’s life more than on her writings and have interpreted her ever-changing romances mostly in psychological terms, as resulting from a repressive childhood and conflicts with her mother. This much is true: Reventlow’s personal rebellion did not always correlate with the collective rebellion of the growing women's movement, she did not present herself as politically-minded, she was explicitly not a feminist, and her occasional social criticism was apparently motivated by individual needs rather than social involvement. Nevertheless, her writings do have political implications. By publicly treating taboo topics as she did in her literary works and by explicitly applying Nietzsche's call for the re-evaluation of all values to both sexes, she provided models of women’s independence and self-determination regarding marriage, sexuality, and motherhood and helped to subvert some of the anti-hedonism, anti-individualism, and blind allegiance to authority then prevalent in imperial Germany.

Author: Katharina von Hammerstein

Quotes

I will and must become free one day; deeply ingrained in my nature is this uncontrollable striving and longing for freedom. The smallest fetter that others may not perceive as such, weighs upon me unbearably and I must engage in a battle against all fetters and restraints. I have felt this way all my life [...]. Mustn’t I free myself, mustn’t I rescue my inner self—I know that I will perish if I don’t.

Thank God, the Christian morals of our society have become fundamentally outdated over these past few decades; the movement of modernity has taught the young generation some of that courageous joyfulness of paganism. We have started to chip away at the old tablets of laws.

In our enthusiasm and pathos we felt like the avant-garde of a new age—at any moment we would have been willing to sacrifice ourselves for it. [...] But who may have bled for it more than I?—Indeed, ‘that ultimate courage to be oneself’—a bloody path leads you there,—it makes your feet raw and tired.

Literature & Sources

Faber, Richard. Franziska zu Reventlow und die Schwabinger Gegenkultur. Köln/Germany: Böhlau, 1993.

Hammerstein, Katharina von. “Politisch ihrer selbst zum Trotz: Franziska Gräfin zu Reventlow,” Karin Tebben (ed.). Deutschsprachige Schriftstellerinnen des Fin de Siècle. Darmstadt/Germany: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1999. 290-312.

Kubitschek, Brigitta. Franziska Gräfin zu Reventlow. Leben und Werk. München/Germany: Profil Verlag, 1998. Reventlow, Franziska zu. Ellen Olestjerne. München: Marchlewski, 1903. Neuauflage. Mit einem Nachwort von Gisela Brinker-Gabler. Frankfurt a. M./Germany: Fischer, 1985.

“Wir üben uns jetzt wie Esel schreien…” - F. Gräfin zu Reventlow, Bohdan von Suchocki, Briefwechsel 1903-1909, hg. von Irene Weiser, Detlef Seydel & Jürgen Gutsch. Verlag Karl Stutz. Passau 2004

“Wir sehen uns ins Auge, das Leben und ich” - F. Gräfin zu Reventlow, Tagebücher 1895-1910, aus dem Autograph textkritisch neu herausgegeben und kommentiert von Irene Weiser & Jürgen Gutsch. Verlag Karl Stutz. Passau 2006.

Székely, Johannes. Franziska Gräfin zu Reventlow. Leben und Werk. Mit einer Franziska-Gräfin-zu-Reventlow-Bibliographie. Bonn/Germany: Bouvier, 1979.

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.