German astronomer

born March 16, 1750 in Hannover

died January 9, 1848 in Hannover

Biography • Literature & Sources

Biography

Caroline Lucretia Herschel was the first woman to receive full recognition in the field of astronomy. She grew up in Hanover, the only girl among five surviving children of the military musician Isaak Herschel and his wife Anna Ilse Herschel. Against the wishes of her mother, who would have preferred her to be a seamstress, Caroline, like her brothers, received musical training and became a concert singer.

When she was 22 she followed her brother Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel (her elder by twelve years) to England, where he was an organist and conductor in the elegant city of Bath. He needed her as his housekeeper, but also gave her the opportunity to appear as a soloist in his concerts. Soon she had gained the position of first singer, assumed a managerial role in the chorus and received offers to perform in other cities. She would surely have had a great musical career had she not followed her brother's passion for astronomy. Without doubt this was an unusual family, these Herschels from Hanover, among whom great gifts, even double talents (music and astronomy) were apparently the rule: Alexander, also a musician, served as well as an astronomer in brother Wilhelm's family business of studying the skies.

When she was 22 she followed her brother Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel (her elder by twelve years) to England, where he was an organist and conductor in the elegant city of Bath. He needed her as his housekeeper, but also gave her the opportunity to appear as a soloist in his concerts. Soon she had gained the position of first singer, assumed a managerial role in the chorus and received offers to perform in other cities. She would surely have had a great musical career had she not followed her brother's passion for astronomy. Without doubt this was an unusual family, these Herschels from Hanover, among whom great gifts, even double talents (music and astronomy) were apparently the rule: Alexander, also a musician, served as well as an astronomer in brother Wilhelm's family business of studying the skies.

In addtition to running the household and her appearances as a singer, Caroline now devoted herself to astronomy; for example she helped Wilhelm produce reflecting telescopes. Her main duty consisted in grinding and polishing the mirrors – a task that required absolute accuracy. Besides such practical activites however, she occupied herself with astronomical theory. She mastered algebra and formulas for calculation and conversion as a basis for observing the stars and measuring astronomical distances.

The great breakthrough came for Caroline Herschel in 1781, the year the planet Uranus was discovered, which her brother had found more or less by chance when surveying the stars. This discovery led to his international fame: in addition to numerous honors he was offered a position as royal astronomer to the court at Windsor which he gratefully accepted. Now he was able to dedicate himself entirely to his true passion.

Caroline Herschel now faced a choice: whether to continue her career as a singer or to “serve” her brother as his scientific assistent. She chose the latter and was appointed by the court as a qualified assistant with a salary of 50 pounds per year – the first salary that a woman had ever received for scientific work.

Now Caroline began her own astronomical research, specializing in the search for comets. Between 1786 and 1797 she discovered eight of them. Whole nights through she worked with her brother observing the heavens, noting the positions of the stars as he called them to her from the other end of the giant telescope that they had built themselves. She evaluated the nocturnal notations and recalculated them, wrote treatises for Philosophical Transactions, discovered fourteen nebulae, calculated hundreds more, and began a catalogue for star clusters and nebular patches. In addition she compiled a supplemental catalogue to Flamsteeds Atlas which included 561 stars, as well as a comprehensive index to it. For this work she was paid the highest tribute by Gauss and Encke, among others. Nonetheless she remained the (excessively?) modest woman she had always been.

Now Caroline began her own astronomical research, specializing in the search for comets. Between 1786 and 1797 she discovered eight of them. Whole nights through she worked with her brother observing the heavens, noting the positions of the stars as he called them to her from the other end of the giant telescope that they had built themselves. She evaluated the nocturnal notations and recalculated them, wrote treatises for Philosophical Transactions, discovered fourteen nebulae, calculated hundreds more, and began a catalogue for star clusters and nebular patches. In addition she compiled a supplemental catalogue to Flamsteeds Atlas which included 561 stars, as well as a comprehensive index to it. For this work she was paid the highest tribute by Gauss and Encke, among others. Nonetheless she remained the (excessively?) modest woman she had always been.

In 1822, a few short weeks after her brother's death, Caroline Herschel returned to her home city of Hanover, which she had left as a young woman almost fifty years earlier. The world's most important scientists sought her out in her simple house on Marktstraße. She was awarded numerous honors – for example in 1828 the gold medal of the Royal Astronomical Society, of which she was named an honorary member in 1835. In 1838 the Royal Irish Academy of Sciences in Dublin appointed the 88-year-old Caroline Herschel to its number. And in 1846, at the age of 96, she was awarded, on behalf of the King of Prussia, the gold medal of the Prussian Academy of Sciences.

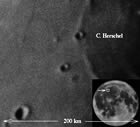

None of the comets she discovered was named after her, but a crater of the moon bears the name Caroline Herschel.

transl. Joey Horsley

Author: Julie Schröder

Literature & Sources

Buttmann, Günther. 1961. Wilhelm Herschel: Leben und Werk. Große Naturforscher, Band 24. Stuttgart. Wissenschaftl. Verlagsges.

Buttmann, Günther. 1961. Wilhelm Herschel: Leben und Werk. Große Naturforscher, Band 24. Stuttgart. Wissenschaftl. Verlagsges.

Feyl, Renate. 1991. “Caroline Herschel (1750-1848): Aufbruch in die nicht gewollte Selbständigkeit”, in: Schroeder, Hiltrud. Hg. 1991. Sophie & Co.: Bedeutende Frauen Hannovers. Hannover. Fackelträger. S. 45-56.

Helle, Christiane. 2000. Die Sternguckerin: Leben und Werk der Astronomin Caroline Herschel. Ein Feature mit Hannelore Hoger und anderen SprecherInnen. 1 CD. Audio Verlag, Dav.

Herschel, Caroline. 1877. Memoiren und Briefwechsel 1750-1848. Hg. Frau John Herschel. Berlin.

Mädler, Dr. J. H. von. 1873. Geschichte der Himmelskunde. Braunschweig. Westermann.

Moore, Patrick. 1988. Caroline Herschel: Reflected Glory. Bath. Ralph Allen.

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.